This year was meant to be a comeback year for America’s schools — a return to classrooms and rebuilding of communities after months of remote or hybrid learning, disconnection, and uncertainty.

And for many schools, it was, at least for a while. Schools fully reopened. Vaccines were available for teens and would soon be for children over 5. Districts mapped out how to spend an unprecedented amount of COVID relief money.

But the buildings that swung wide their doors to students in the fall of 2021 were changed schools. Staff saw learning loss, behavior issues, and mental health challenges from the trauma of the pandemic. Students faced violence, in their communities or in schools themselves. Some districts faced crippling staffing shortages, struggling to fill not only teaching positions but those for nurses, cafeteria workers, bus drivers, and social workers.

Then the pandemic took on a new shape, with the delta and then omicron variants causing disruptions that school leaders had hoped were behind them. The result: temporary shifts back to remote learning, widespread student absences, teachers out sick, and, in some cases, pitched debates about how to balance student needs with health and safety.

Chalkbeat has chronicled this seesawing school year up close for the last 10 months. As this third year of disrupted learning draws to an end, reporters from our eight local bureaus interviewed members of school communities about the highs and lows of the year, how they’ll remember this time, and what lessons they’ll take with them from a comeback year that didn’t always feel like one.

Kira Badberg, student teacher, Lowry Elementary School, Denver

Kira Badberg sees shadows of the pandemic on the young lives of her preschool students.

Some children, used to eating anytime while they were at home, struggled to wait for snack at 9:30 a.m. or lunch at noon. Others acted out, saying “no” when asked to draw a letter on a whiteboard, kicking a classmate who didn’t hand over a toy, or even spitting at teachers.

“There’s always been challenging behaviors,” said Badberg, a student teacher at Lowry Elementary in Denver. “But now it just seems like there’s four or five, or seven or eight more.”

It’s no surprise. Many young children spent the most critical brain-building period of their lives in stressful or at least unusual circumstances — anxious parents, more screen time, and fewer playdates. Badberg, who’s upbeat with a ready smile, has learned to head off problems before they escalate, sometimes setting timers to help kids share or giving them choices when they begin to shut down.

The 22-year-old graduated from the University of Colorado Denver in May with a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education. She was part of a para-to-teacher program called NxtGEN Teacher Residency, which aims to help students of color, first-generation college students, and students who speak multiple languages enter teaching.

In addition to college classes, the program includes three years of paid part-time work as a paraprofessional — another name for a teacher’s aide — and a year-long student teaching assignment. Badberg, a first-generation college student, worked at Lowry all four years.

During her junior year, when it seemed like she spent most of her waking hours on Zoom, either for her para job or her college classes, things “felt really overwhelming and really hard,” she said. But connecting with Lowry students kept her going — talking about simple things like what they had for dinner or hearing them playfully rename her “Miss Goodberg.”

Badberg already has a job lined up for the fall. She’ll be a kindergarten teacher at Lowry — a beginner and a veteran at the same time.

— Ann Schimke

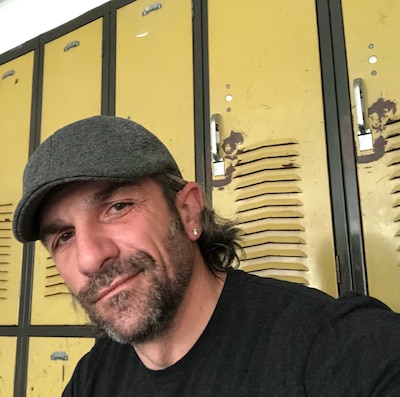

Christopher Rasidakis, eighth grade English teacher at I.S. 238 in Queens, NY

Teaching has always been a passion for Christopher Rasidakis, known by his students at his Queens middle school as “Mr. R.”

But after teaching in NYC for 20 years, he is not returning to the classroom this fall. He has never wanted to do the job just to collect a paycheck.

“Emotionally, I’m drained and damaged from COVID,” he said. “If you can’t be there to uplift others, then you’re not serving your kids. I’m doing it this year, but at a cost to myself.”

When students and staff returned to I.S. 238 full time in September, the school community was still reeling from lives lost to COVID, including a beloved teacher, Tammy Hendricks, who died from the virus in April 2020.

Rasidakis’ students have been “warriors,” showing up despite hardships and displaying kindness to each other in a year filled with uncertainty — the rise and fall and rise of coronavirus cases, masks on and then off (though the majority still wear masks because of vulnerable family members, Rasidakis said).

But it’s been hard to watch how students’ confidence has been shattered by prolonged learning disruptions and difficulty readjusting to classrooms. They returned to a slew of academic assessments, and, unsurprisingly, many did not do well on them.

“Everything says: they’re behind, they’re damaged,” Rasidakis said. “Many came back and thought ‘I’m stupid.’”

‘Teaching is my heart and soul,’ he said. ‘To leave it, a part of me is going to be missing.’

Rasidakis has been trying to rebuild their writing skills and faith in their abilities.

Getting students to be engaged again can feel like an uphill battle. The school, like many across the city, is struggling with absenteeism and lateness. And in many ways, Rasidakis feels like people are blaming teachers for these and other problems, which has only made the situation less tenable for him.

He wants to continue working with children, whether as a coach or working at a camp, or even in education law if he decides to pursue a legal degree.

“Teaching is my heart and soul,” he said. “To leave it, a part of me is going to be missing.”

– Amy Zimmer

Lisa Thibault, parent, Pike Township, Indiana

One morning last October, Lisa Thibault’s daughter texted her that the bus was late again, and school was starting in less than half an hour.

Thibault drove to the bus stop to see a group of students still waiting in the chilly, dark Indiana morning.

“I rolled down my window to the kids standing there and told them, ‘Hey, I’m going to the school,’” Thibault said. “So I took a couple kids to school that day.”

Whether the bus would come had become a source of anxiety for Pike Township families last fall. A high number of driver vacancies, overlapping sick leave, and demonstrations for better pay and benefits forced the district to intermittently return to virtual learning throughout the first semester.

When in-person school was in session, Thibault said her sophomore daughter relied on the bus, using a district app that was supposed to notify them when the bus was en route. But the notifications — along with the bus — were sporadic.

The most stressful days were when the district canceled in-person school entirely due to transportation issues. While one teacher held classes by video chat, most assigned independent work, Thibault said. Some classes — like art and orchestra — were impossible to hold online.

Thibault said her daughter suffered from lack of socialization, as well as the daily uncertainty over whether she’d be in school and whether tests and assignments would be postponed. In total, about a month’s worth of school was disrupted, she said.

“I was lucky that I had a kid who could take care of herself,” she said. “But her grades suffered because of it all.”

The situation began to improve in the second semester, Thibault said. The district signed a new contract with its teachers in December after months of contentious negotiations. It parted ways with its superintendent and promised raises for bus drivers.

Thibault said the transportation issues have mostly been resolved. She credited the drivers with remaining friendly and welcoming all year, always holding the bus when Lucy was running to catch it.

Though her daughter is learning to drive, it’s likely that they’ll still rely on the bus for some time next year, Thibault said.

“Hopefully,” she said, “it’ll show up.”

– Aleksandra Appleton

Kaitlyn Stewart, student, Englewood STEM Academy, Chicago

It was dismissal time when the gunshots rang out.

Kaitlyn Stewart and her classmates at Englewood STEM Academy in Chicago scattered, unsure whether to run back into the school building or to nearby cars. Seeing police arrive with guns in hand put “more fear into our bodies,” she recalled.

In an email from school administrators later that day, families learned that the shooting occurred in a nearby home and had nothing to do with the school community.

The trauma of the incident, part of a wave of gun violence that has shaken Chicago this past year, still weighs heavily on Kaitlyn as she reflects on her challenging sophomore year.

The day after the shooting, Kaitlyn stayed home because she was scared. School officials urged parents to alert homeroom teachers if their child had concerns and needed extra support. Kaitlyn, though, said gun violence is not a topic readily discussed at school. Kaitlyn and her close friend talked about transferring. She still thinks about it.

Kaitlyn can’t help but think the uptick in violence is connected to the trauma of the past two pandemic years, especially for those most directly affected.

“Maybe the pandemic has caused some of this violence because people were suddenly losing so many people,” she said.

Going into this school year, Chicago Public Schools had a plan for meeting the mental health needs of students shaken by the pandemic, including expanding “care teams” on campuses — first responders of sorts for struggling students. But last year, gun violence claimed the lives of 57 school-aged children. That prompted the district to expand an anti-violence program for teens in “high-risk situations,” connecting them with weekly therapy and dedicated mentors.

Kaitlyn doesn’t know what the answer is, but she would like to see more mental health support for students,including therapists.

In a poem she wrote in the fall, Kaitlyn wrote that violence “takes a toll on our life:”

“We want to be in a world full of fun,

not a world where we have to watch our back everywhere we go.

We don’t want to be in a world where we live in fear all around us.”

— Mauricio Pena

Tiffany Chavous, director, Somerset Academy Early Learning Center, North Philadelphia

Tiffany Chavous steered Somerset Academy Early Learning Center through the pandemic.

Now she faces new challenges – children’s behavior issues made more challenging by staffing shortages.

Chavous, director of the North Philadelphia center offering preschool and after-school care, credits her “teachers for getting through the height of the pandemic. The center initially opened only for children of essential workers, and a core group of teachers pledged to limit their interactions beyond work and home in an effort to keep each other safe.

“We kept our circles really small,” Chavous said.

As the world reopened, student enrollment increased. The center now serves 122 students, up from 70 pre-pandemic, Chavous said. Families who arrived during the pandemic stayed, and new families have enrolled based on the center’s reputation for working with children with behavioral or developmental issues.

But, like child care centers across Pennsylvania and the nation, Somerset Academy has seen staff slip away. Some staff with underlying health conditions no longer felt safe returning to in-person teaching. Others are seeking out different professions.

Many early childhood teachers left for higher-paying jobs, Chavous said, noting that teachers can make more at big-box retailers or fast-food outlets. “Because of that, it’s been very, very difficult to get quality staff,” she said.

The center has 12 teachers but is in search of three more. In the meantime, interns and parents are covering for the vacancies.

But Chavous knows about being resourceful. During the pandemic, college interns have provided activities such as dance and music therapy.. And Somerset, which has a behavioral specialist on staff, created an interactive science center where kids could get hands-on experiences, she said.

Early in the pandemic, when students at the center logged into their schools’ remote classes, center staff developed a reward system that allowed those who completed their work to pick prizes or earn extended time outside. “We tried to create a fun atmosphere for children who did not want to be on Zoom,” Chavous said

Instead of focusing on problems, she said, “we try to create solutions.”

– Nora Macaluso

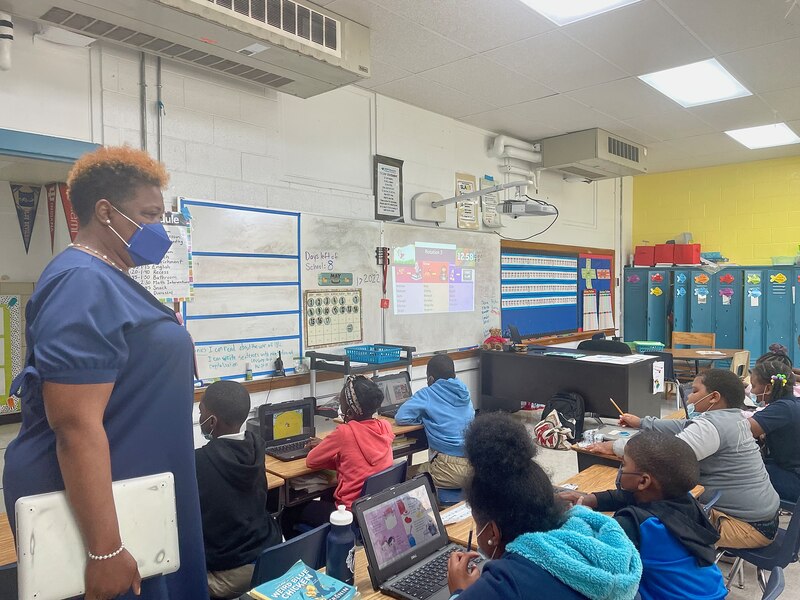

Veda Turner, principal, KIPP Memphis Collegiate Middle School, Memphis

This school year, Veda Turner’s workday began as soon as she woke up.

The principal at KIPP Memphis Collegiate Middle School would roll out of bed each weekday and check her email, taking measure of the staff members who were out and game-planning how she would fill their absences at the charter school in Uptown Memphis.

“Well, it’s a good thing I love puzzles,” Turner said as she walked down a school hallway on a recent Tuesday before the school year ended. “Each day is a different story.”

This year was supposed to focus squarely on academic recovery for the school’s nearly 350 students after a year of remote school. But that turned out not to be the case, Turner said, because of staffing issues and a dip in student attendance as the pandemic continued to take a heavy toll.

On many occasions, Turner said she didn’t have enough substitute teachers to cover for staff absences — especially during the fall’s delta wave and January’s omicron surge.

That meant shuffling staff members around when possible and at times teaching a class herself to ensure her students — most of whom are Black, come from economically disadvantaged families, and were disproportionately affected by the pandemic — continued learning.

Turner said she would rather put herself in a classroom than add any more to her already-stressed educators’ plates. For over three months, Turner taught a sixth-grade English class — even though her past classroom experience was mostly teaching science.

“Regardless of who was out, who was in, (the students) still needed to receive instruction,” Turner said. “So I did what I’ve always done: I put my strongest available people in front of kids in places where they’re needed. If I didn’t have that strong person, that means I did it.”

– Samantha West

Marcia Spivey, parent, Edmonson Montessori Elementary School, Detroit

Marcia Spivey felt helpless and frustrated.

Her son, Rinzer, had easily mastered pronouncing three-letter words last year as a kindergartner through all-remote instruction.

Now, in first grade and in person, he was struggling to grasp basic phonics instruction. Interactive Leapfrog books became supplemental exercises to test his ability to sound out words like yellow, blue, and orange. He often asked his second-grade sister to read for him.

While Spivey prides herself on being actively engaged in her children’s learning, she also recognized her limits.

“I got to do my part because I’m the mom, but I’m not a teacher,” she said. “So I don’t necessarily know how to teach consonants.”

By the end of January, school assessment results confirmed Spivey’s worries: Rinzer had fallen below grade level in reading since the year began. His school, Edmonson Montessori, responded by offering him and other students tutoring sessions.

After years of poor academic performance that drew unwelcome national attention, the Detroit Public Schools Community District has seen steady gains and improved attendance. The pandemic put that in jeopardy; district leaders have responded by setting aside federal COVID relief dollars for tutoring, reducing class sizes, and expanding mental health support.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti emphasized at the start of the year that in-person learning was the best choice for students who needed to recover academically.

Then in January, as omicron took hold, the district returned to remote learning — leaving parents like Spivey to supplement teaching from online classes.

Rinzer’s confidence in his reading improved when in-person learning resumed, Spivey said. Still, she worries whether the academic gains her children made in the second half of the school year will be lost over the summer months — setting him back again.

— Ethan Bakuli

Tracy Russ, parent, Thirteenth Avenue Elementary, Newark

For Tracy Russ, a Newark parent of three children who attend district-run schools, this school year was a time of renewal.

Her children learned new things, like how to dance, swim, read, and play new instruments. They also put down their devices, went to the movies, and made new friends – things they hadn’t done since the pandemic began.

But the change wasn’t as easy as flipping a switch, Russ said.

“Throughout the pandemic, we all picked up on bad habits with our devices,” Russ said. “I said, ‘Tracy, you need to get them back out in the world.’ ”

And that’s what she did.

In the early spring, she signed up her daughters, Tahlia, 10, and Samaya, 8, for dance classes at Newark School of the Arts. Her son, DaJuan, 11, started taking swim lessons through a city-sponsored program for children like him who are on the autism spectrum.

“The computers, being bored at home, depression — it was all starting to consume me and my kids,” she said.

Russ had concerns about COVID safety protocols at Thirteenth Avenue Elementary, which her children attend, and she also worried her children were falling behind academically during remote and hybrid learning. Two of her children have individualized education plans, a document that outlines specialized instruction and services they need.

In addition to being on the autism spectrum, DaJuan has Dandy-Walker syndrome, a congenital brain malformation that makes it difficult for him to control his movements. Samaya has challenges regulating her emotions, and her specialized learning plan calls for a one-on-one aide, Russ said.

While DaJuan received speech, occupational, and physical therapy all year, because of a shortage of classroom aides, Samaya couldn’t receive one-on-one services, Russ said.

Even so, Samaya thrived this year, socializing and getting A’s on spelling tests. Though the vast majority of students struggled with standardized tests this year, Tahlia scored on or above her fourth-grade level, Russ added.

And one afternoon in May, Russ received an unexpected text message from DaJuan’s classroom aide.

“I want you to see what DaJuan is doing.”

Russ pressed play on the attached video and watched her son play the C chord on a ukulele during music class.

“Just seeing the excitement and focus from him, and his teacher telling him to play this chord, and for him to be able to pick it up and do it,” she said, recalling the moment through tears.

DaJuan also made a breakthrough with reading. As Russ and DaJuan waited for Samaya and Tahlia to finish dance rehearsals on a recent Thursday, she was overwhelmed as she watched him read a book aloud.

“I see so much growth in all of them,” Russ said. “And even in me.”

— Catherine Carrera