For-profit colleges are spreading faster than dandelions in Colorado, fertilized by a relatively lax regulatory environment and an increasing demand for post-secondary training and degrees – and despite increased scrutiny of the schools nationwide.

While people hold mixed views of schools like the University of Phoenix, DeVry University and a host of vocational schools, such schools likely are here to stay and to play an even greater role in future years if the state’s funding of higher education continues to dwindle.

In fact, public colleges and universities are trying new approaches to online learning and degree programs to compete with them – or risk losing students.

There are about 350 for-profit post-secondary schools in Colorado, including 33 that offer baccalaureate degrees or higher, according to the Colorado Department of Higher Education. The schools enroll roughly a quarter of the state’s 375,168 post-secondary students.

Over the past five years, the number of for-profit, vocation-oriented schools in Colorado, covering professions such as real estate and nursing, has grown 5 percent per year. This year, though, the number of occupational schools climbed 12 percent, according to the department’s Division of Private Occupational Schools.

During that same five-year period, the number of degree-granting private colleges (not including tax-exempt religious schools) rose 27 percent from 45 to 57 due, in part, to a surge in for-profit schools operating here. As of 2008, about 56,000 students were enrolled in for-profit, degree-granting colleges and 38,000 were enrolled in for-profit occupational programs.

“We have a rich market,” said Rico Munn, executive director of the Colorado Department of Higher Education. “You’ve got a broad range. We have some fly-by-night programs that need to be dealt with, then you have some very legitimate, strong programs.”

Munn said that Colorado is “relatively speaking, an easier place to get credentialed as a private institution” since the state’s legal framework “provides a little more room for that type of entrepreneurship.”

Students are looking for opportunities in a state where some public colleges are maxed out, said Jim Parker, director of the department’s Division of Private Occupational Schools.

“Community colleges are full,” Parker said. “They’re having to turn some students away so students are looking at private occupational (schools). I think they serve a very valuable need. As private businesses that are for-profit, they really respond to market need right now.”

Community College of Aurora President Linda Bowman, who formerly worked in the proprietary sector, said enrollment at her campus climbed 20 percent this year. She said certain intensive programs, such as nursing, are expensive to deliver. CCA has a new partnership with the University of Colorado’s School of Nursing expected to attract additional students but overall, she said, community colleges can’t keep up with demand.

“It’s very expensive for state-supported schools,” she said. “The fact that we try to keep the tuition so low results in our having a lack of capacity compared to demand and an inability to charge exactly what it costs.”

Cooperate or compete?

Increasing competition from for-profit colleges leaves many in the public sphere wondering what to do to maintain an edge. Lower tuition isn’t always enough.

University of Northern Colorado President Kay Norton has spent a good deal of time thinking about the role for-profit schools play. In the old days, UNC was the be-all end-all in teacher education. Those days are gone and UNC is now in the position of competing against for-profit schools, which often have robust marketing budgets and much more flexibility to respond quickly to market demand. It can take months for a public school to launch a new degree program.

Norton, who describes herself as “a free-market gal,” said she had to wage a good fight in support of a new master’s degree in accounting at UNC, which she ultimately won. Initially, state regulators posed tough questions about how the program fit into the school’s statutory mission, which is supposed to be in the field of education.

“What (for-profits) get to do is to cherry-pick the programs that are revenue producers and they have no obligation to provide the programs that are net revenue losers but may be absolutely essential to the public interest,” Norton said.

Norton said policymakers tend to ignore the impact of for-profits on the higher ed market.

“We have tended to focus on perceived rivalries among ourselves,” she said. “We’ve got to understand the new reality: The folks that are eating your lunch are not the public institutions down the road but these for-profit providers.”

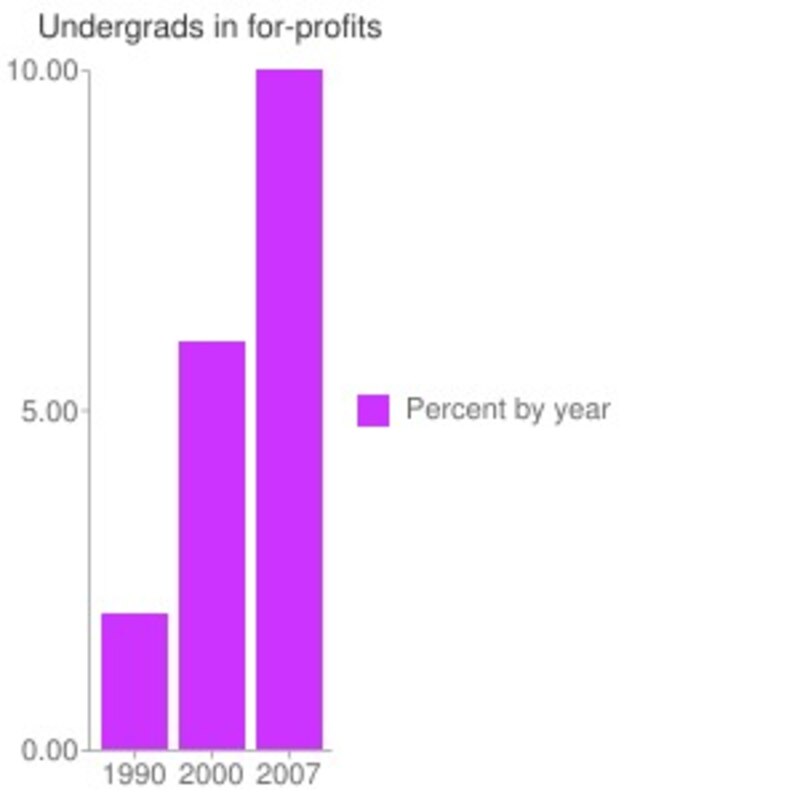

It’s unclear whether this is happening in Colorado – yet – although Norton believes UNC has lost some market share in the field of education. The College Board found that the percentage of full-time undergraduates enrolled in for-profit schools increased from 2 percent in 1990 to 6 percent in 2000 and 10 percent in 2007. The shares of students enrolled in all other sectors declined over the same period.

While Norton wouldn’t support regulating the for-profits out of existence, she would like to see more oversight of the schools – though she calls certain ones, such as the University of Phoenix, “legitimate.”

“I don’t expect the state to protect us,” she said. “What I do expect is the state to protect the consumers of Colorado from being taken advantage of by an entity that may be interested more in churning student loan funds rather than providing a transformational educational experience.”

For-profit schools tout expanded access

Wallace Pond, chief executive officer of Colorado Technical University, agrees with Norton’s assessment that for-profit schools – he makes sure to call them “taxpaying schools” – do have “the luxury of focusing only on a career-minded curriculum that leads directly to jobs.”

“We don’t have football teams. We don’t have huge, 200-acre physical plants,” Pond said. “We don’t have art museums on campus. All we do is teach students. It doesn’t mean that Colorado State University or Pikes Peak Community College can’t do that, they do. But they don’t do it with singularity of purpose.”

He believes for-profits will play a vital role in the future of higher education because they have to. President Obama has a policy initiative aimed at increasing the number of Americans with college degrees or post-secondary workforce training.

“That is unachievable by pure mathematics without the for-profit sector playing a significant role,” Pond said. “The traditional sector does not have the capacity to educate a significantly greater numbers of students.”

For the for-profits, which are beholden to stockholders, constant growth is built into the business model.

Colorado Technical University began in this state as Colorado Tech in 1965. Over 35 years, the name changed and enrollment rose to 3,000. Then it became a university. Between 2001 and 2010, enrollment ballooned to 32,000. The majority of its students – or 27,000 – do their coursework online. The hottest fields are business, criminal justice and health sciences, such as nursing and surgical technology.

“As a taxpaying institution, we clearly take a different view of admissions than schools do who cannot support growth,” he said. “We have to grow with quality and in a scalable way.”

In Colorado, proprietary schools may play an even greater role than in other states due to the state’s funding challenges. State funding for higher education is at risk of being chopped in half, from $600 million to $300 million in fiscal 2011-2012, a year some call “the cliff,” because that’s when federal stimulus funds go away.

“The taxpaying sector can really play a role,” Pond said. “Institutions like Colorado Tech, we get zero government support other than financial aid. The cost of educating a student at CTU is significantly less in public dollars than it is at public schools. We don’t get any legislative appropriation and we pay taxes back into the system.”

The University of Phoenix has experienced similar growth. Phoenix has been in the Colorado area since 1982 and has seven locations in Aurora, Colorado Springs, Fort Collins, Lone Tree, Pueblo and Westminster with more than 500 employees and faculty members. Some 8,600 students are enrolled in the schools, University of Phoenix spokesman Manny Rivera said.

Since the schools started here, he said, 25,000 people have earned their associate’s undergraduate and graduate degrees in business, criminal justice, education, nursing and health care, social and behavioral sciences, and technology via online program or by attending classes at a bricks-and-mortar campus.

“University of Phoenix prides itself on opening doors to educational opportunities for many students who would not otherwise have access to higher education,” Rivera said.

Nationwide, more than 458,000 students are enrolled at the University of Phoenix “pursuing a curriculum that is attuned to the current job market,” he said. At University of Phoenix’s Colorado locations, the most popular degree programs are in business, education and healthcare.

“Our business programs remain in high demand given the variety of specializations offered by the university,” Rivera said. “For example, students can earn bachelor’s degrees in business with a special concentration in supply chain and operation management, account, e-businesses, global business management, green and sustainable enterprise, human resources management and hospitality management.”

The University of Phoenix in Colorado also has offered a range of programs and scholarships aimed at teachers.

“The university recognized the need to improve early childhood education and created a master’s degree program in that specialization,” he said. “With the state’s focus on improving early childhood services to increase school-readiness, there has been increased interest from individuals for this type of degree.”

Questions linger about for-profit schools

Despite the ability of the for-profits to fill critical skill areas, Munn and others remain wary of the quick rise of the colleges, especially as recent news reports detail some of the schools’ high-pressure student recruitment practices, promises of future salaries that may never materialize and potentially crippling student debt. (This recent PBS Frontline documentary about for-profit colleges generated a lot of buzz.)

Munn said his office has fielded more complaints against for-profit colleges in the past couple years. In 2006, there were nine complaints filed against mostly for-profit private colleges for issues primarily related to academics and financial aid. In 2009, that number climbed to 80 complaints. Through March of this year, there have been 17 complaints filed.

Of the total 142 complaints filed since 2006, only 25 remain active. Many get dropped because a student failed to follow proper protocols at the institutional level first or students signed legally binding documents without reading the fine print.

Since September, the state has revoked authorization of three for-profit schools.

The Colorado Attorney General’s office, meanwhile, is investigating 51 complaints filed by students or their parents against Westwood College in the past three years. (The Denver Post chronicled these issues in January.) The complaints include schools not being up front about the transferability of credit or about the actual cost of attendance.

“The biggest concern students at for-profit schools should have is the transferability of their credits,” said Marsi Liddell, president of Greeley-based Aims Community College, a public school. “Many non-profit colleges and universities will not accept transfer credits from for-profit schools. This can be a limiting reality for students who may want to advance their education with a higher degree.”

Others, though, believe for-profit proprietary schools have been tarnished by the bad deeds of a few.

“For a long, long time, for-profits have been vilified,” said Bette Matkowski, president of the non-profit but career-focused Johnson & Wales University in Denver. “I think now people are realizing the landscape is rich enough and big enough that there’s room for everybody. The match is the most important thing.”

State incorporates for-profits into strategic plans…kind of

A strategic planning process is now underway in Colorado to make sure the public system of higher education is sustainable and can meet the state’s future economic needs.

While representatives of the for-profit schools are not participating directly in the planning process, two subcommittees are expected to make recommendations regarding the transfer of credits between public and private institutions. During the recently concluded legislative session, a bill passed that opened up the credit transfer pathway that had existed just for the public colleges and universities to privates, including for-profits.

Pond believes at some point, the for-profits should be invited to join the conversation.

“The the state really has to get their arms wrapped around what it means to be a public institution in Colorado,” Pond said. “Once they get that figured out, the private sector can play an important role to help envision the future of higher education in Colorado. That diversity of higher education is a real asset if we see it as such and use it as such.”

Higher education leaders involved in the planning process, however, make it clear the meetings are focused on public higher education in the state – not for-profit schools.

“We’re certainly aware and understand these institutions have a role to play,” said strategic planning co-chair and attorney Jim Lyons. “But it would be inappropriate to have them at the table. Our mission and charge of the governor is to look at publicly funded education.”

But some public/for-profit partnerships are underway.

The most recent partnership was announced Tuesday, when Colorado Technical University, with campuses in Denver, Westminster, Colorado Springs and Pueblo, said an articulation agreement with the Colorado Community College System had been approved that will allow community college students with certain associate’s degrees to transfer credits and receive tuition grants for bachelor’s degree programs at CTU.

For example, a student who earns an associate of applied science in criminal justice from a community college can transfer a maximum of 22.5 credit hours toward a CTU bachelor of science in criminal justice and be considered a junior right out of the gate. Students can also qualify for a 30 percent break on tuition their junior year and a 20 percent tuition grant their senior year.

In a news release, Pond highlighted the fact that students would be able to pursue a bachelor’s degree at CTU at “a reduced cost and in less time than it would take at other universities where their credits may not transfer as easily.”

It is one of eight such agreements with for-profit schools now available to Colorado’s community college graduates.

“On the public side, as resources become more scarce, articulation agreements are becoming more and more of a vehicle to share resources and educational opportunities,” Pond said.

Tighter federal regulations being discussed

While few can deny for-profit colleges play a vital role in higher education, concerns about some practices, such as false promises to prospective students who end up graduating – or not – with a mountain of debt and weak job skills, continue to gain the ear of some policymakers in Washington. Specifically, a U.S. Department of Education proposal would cut federal aid to schools where a majority of student loan payments exceeded 8 percent of expected earnings upon graduation based on a 10-year repayment plan, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education.

The average debt load from 2006 to 2008 for first-year students in Colorado is much greater at the private schools. First-year students in Colorado who took out loans at private institutions, including non-profits, borrowed nearly 70 percent more than those enrolled at public institutions.

Students generally take out more loans because private schools are significantly more expensive than public ones for the obvious reason that they’re not subsidized. In 2008, the average tuition for an in-state undergraduate at the for-profit Platt College was $22,800. At College America’s Denver campus it was $17,650. At the University of Phoenix’s Denver campus it was $11,575, compared to $5,922 at CU-Boulder or $2,615 at the Metropolitan State College of Denver, according to state data (start at page 9).

Before borrowing, many students qualify for federal student grants. In 2008-2009, for instance, the University of Phoenix, owned by the Apollo Group, received $657 million in federal Pell grants awarded to 230,774 students nationwide. Colorado Technical University joined Phoenix on a list of the top 20 colleges receiving the most Pell grant aid, federal funding designed to help the nation’s neediest students. CTU received $42.9 million in Pell grants awarded to 20,078 students that year, according to a January report by National Consumer Law Center called For-Profit Higher Education By The Numbers.

The for-profits are fighting tighter federal regulation to the tune of $620,000 in lobbying efforts, according to the Chronicle, saying the proposal would limit access to higher education to those who need it most. They are pushing a counterproposal that would include providing students with more detailed information about debt and what they need to do to pay it back.

To Pond, it’s unfair to link the very serious issue of student indebtedness to the for-profit sector. Students at public and non-profit private schools have the same problem.

“It creates a divisive us vs. them dynamic that doesn’t solve the problem,” he said.

What about a student at the University of Denver who graduates with a degree in social work? Should the government tell that person she can’t pursue the degree because she most certainly wouldn’t make enough to repay her loans in a timely manner?

“If (the proposed rule) was applied to all of higher ed, we’d have no teacher education grads, no social work graduates, no police officers,” Pond said. “The argument lacks integrity.”

While federal dollars – both Pell and federal loans – sweeten for-profit schools’ bottom lines and enrollment growth, public institutions are struggling to get by. Meanwhile, enrollment continues to grow and college leaders and policymakers continue to try to come up with a way to create a high-quality, sustainable system of post-secondary education in an increasingly market-driven landscape.

“The for-profits are helping us to have this conversation,” Norton said. “You can’t ignore the fact that they’re providing apparently a service people want – because they’re buying it.”

Reporter Julie Poppen can be reached at jpoppen@ednewscolorado.org.

Key facts:

– A quarter of the state’s 375,168 college students are enrolled in 2- and 4-year for-profit colleges.

– In fall 2008, about 56,000 students were enrolled in for-profit, degree-granting colleges; 38,000 students were enrolled in for-profit occupational schools.

– Over the past 30 years, for-profit institutions nationally have grown roughly 9 percent per year, compared to 1.5 percent for all institutions of higher education.

– The median cost for a student to attend a community college in Colorado is $2,771 compared to $14,441 at a for-profit institution in the state.

– In Colorado, more than 40 percent of federal loans and Pell grants go to for-profit schools.

– 23 percent of students who attended for-profit schools in Colorado were in default on their loans in their first three years compared to 12.9 percent at the community college system.

– 43 for-profit colleges award two-year degrees and certificates in programs already offered throughout the public community college system.

– In 2007-2008, for-profit schools enrolled 81,000 students compared to nearly 108,000 in the community college system.

(Source: May 2010 Colorado Community College System Competition from for-profit colleges )