Teachers at School 107 are up against a steep tower of challenges: test scores are chronically low, student turnover is high and more than a third of kids are still learning English.

All the school’s difficulties are compounded by the struggle to hire and retain experienced teachers, said principal Jeremy Baugh, who joined School 107 two years ago. At one of the most challenging schools in Indianapolis Public Schools, many of the educators are in their first year in the classroom.

“It’s a tough learning environment,” Baugh said. “We needed to find a way to support new teachers to be highly effective right away.”

This year, Baugh and the staff of School 107 are tackling those challenges with a new teacher leadership model designed to attract experienced educators and support those who are new to the classroom. School 107 is one of six district schools piloting the opportunity culture program, which allows principals to pay experienced teachers as much as $18,300 extra each year to support other classrooms. Next year, the program will expand to 10 more schools.

The push to create opportunities for teachers to take on leadership and earn more money without leaving the classroom is gaining momentum in Indiana — where the House budget includes $1.5 million for developing educator “career pathways” — and across the country in places from Denver to Washington. The IPS program is modeled on similar efforts in North Carolina led by the education consulting firm Public Impact.

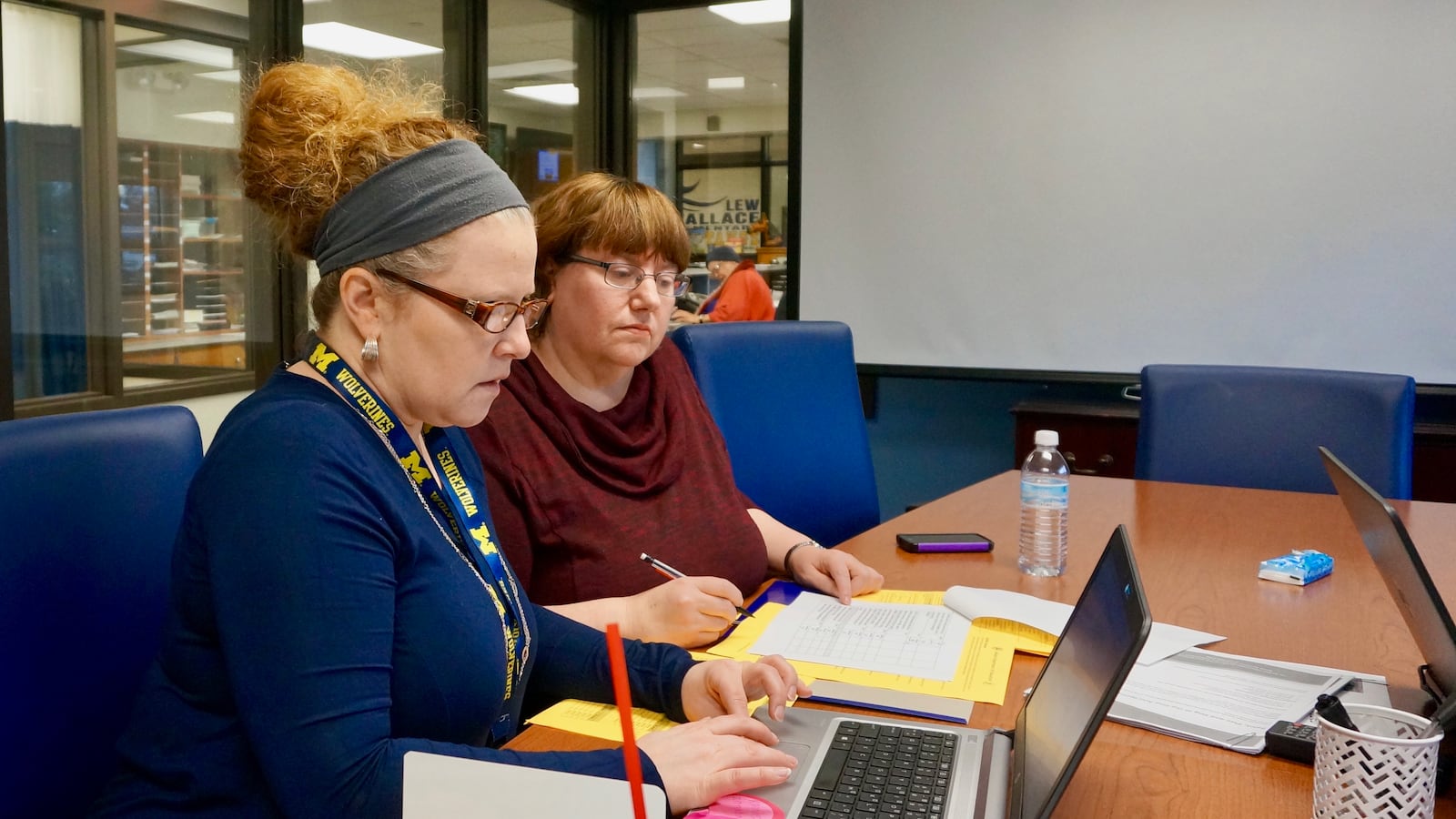

At School 107, Baugh hired three new teachers, called multi-classroom leaders, who are responsible for the performance of several classes. Each class has a dedicated, full-time teacher. But the classroom leader is there to help them plan lessons, improve their teaching and look at data on where students are struggling. And unlike traditional coaches, they also spend time in the classroom, working directly with students.

As classroom leaders, they are directly responsible for the test scores of the students in their classes, said Jesse Pratt, who is overseeing opportunity culture for the district.

“They own that data,” Pratt said. “They are invested in those kids and making sure they are successful.”

At School 107, the program is part of a focus on using data to track student performance that Baugh began rolling out when he took over last school year. It’s already starting to bear fruit: Students still struggle on state tests, but they had so much individual improvement that the school’s letter grade from the state jumped from a D to a B last year.

Paige Sowders, who works with classes in grades 3 through 6, is one of the experienced teachers the program attracted to School 107. After 9 years in the classroom, she went back to school to earn an administrator’s license. But Sowders wasn’t quite ready to leave teaching for the principal’s office, she said. She was planning to continue teaching in Washington Township. Then, she learned about the classroom leader position at School 107, and it seemed like a perfect opportunity to move up the ladder without moving out of the classroom.

“I wanted something in the middle before becoming an administrator,” she said. “I get to be a leader and work with teachers and with children.”

The new approaches to teacher leadership are part of a districtwide move to give principals more freedom to set priorities and choose how to spend funding. But those decisions aren’t always easy. Since schools don’t get extra funding to hire classroom leaders, Baugh had to find money in his existing budget. That meant cutting several vacant part-time positions, including a media specialist, a gym teacher and a music teacher.

It also meant slightly increasing class sizes. Initially, that seemed fine to Baugh, but then enrollment unexpectedly ballooned at the school — going from 368 students at the start of the year to 549 in February. With so many new students, class sizes started to go up, and the school had to hire several new teachers, Baugh said.

Some of those teachers were fresh out of college when they started in January, with little experience in such challenging schools. But because the school had classroom leaders, new teachers weren’t expected to lead classes without support. Instead, they are working with leaders like Sowders, who can take the time to mentor them throughout the year.

With teachers who are just out of school, Sowders spends a lot of time focusing on basics, she said. She went over what their days would be like and how to prepare. During the first week of the semester, she went into one of the new teacher’s classes to teach English every day so he could see the model lessons. And she is working with him on improving discipline in his class by setting expectations in the first hour of class.

Ultimately, Baugh thinks the tradeoffs the school made were worth it. The extra money helped them hold on to talented staff, and they have the bandwidth to train new teachers.

“If I’m a novice teacher just learning my craft, I can’t be expected to be a super star best teacher year one,” he said. “We learn our skill.”