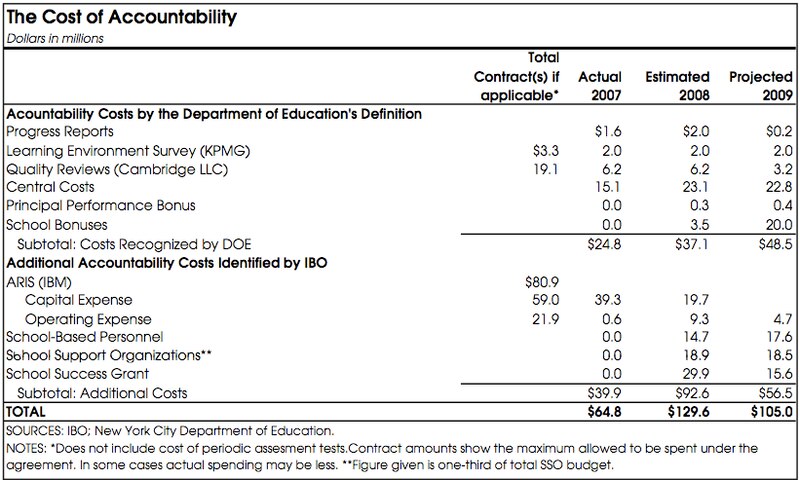

By the end of this school year, the Department of Education will have spent more than $300 million on its accountability initiative, according to a report released today by the city’s Independent Budget Office.

The DOE disputes the IBO’s figure, saying the report includes more initiatives than are actually part of the accountability project. It says the true figure is more like $100 million.

The city’s public advocate, Betsy Gotbaum, commissioned the report, which is bound to intensify debate about whether accountability measures should be cut during the coming budget crunch.

Since it launched in April 2006, the DOE’s accountability initiative has been the engine behind reforms to the way the DOE is structured and the way instruction in city classrooms is delivered. Some have criticized the initiative’s high costs, saying they divert funds from classrooms; the teachers union and other organizations advocate eliminating the DOE’s entire Office of Accountability as a way to save money. But school officials stand by the spending, saying it’s essential to identify students and schools that need help. In a statement today, Schools Chancellor Joel Klein said the IBO “misunderstands the purpose and importance of accountability” and called the DOE’s accountability expenditures “some of the smartest dollars we’ve spent.”

Gotbaum requested the report in February, but it was not completed until now because the DOE was “not being as forthcoming as it could have been” with its budget information, she said this morning at a press conference.

In fact, Gotbaum said the last adjustments to the report were made just minutes before the conference began, after DOE officials called “in a little bit of a panic” to revise estimates of how much school-based accountability personnel cost.

The months-long reporting process also included a prolonged back-and-forth between the IBO and the DOE over what should be considered part of the accountability initiative. Gotbaum said there were “many differences of opinion” about what should be included.

Part of the problem was that the DOE does not clearly define accountability, IBO spokesman Doug Turetsky told me. “There’s no piece of paper that we ever saw that said, this is the accountability initiative,” he said.

According to the DOE, the initiative includes grants for schools and principals whose students do well; the Quality Reviews; the progress reports; surveys of parents, teachers, and students; and personnel at Tweed.

The IBO’s final tally of the DOE’s accountability spending also includes funds spent on the data warehouse called ARIS; some personnel at schools and the School Support Organizations; and money earmarked for schools that received low progress report grades. Turetsky told me the DOE argued that ARIS should be excluded because its uses extend beyond the accountability initiative.

According to the DOE’s definition, its accountability initiative will have racked up costs of just over $100 million by the end of this school year. By the IBO’s, that figure is closer to $300 million.

And to Gotbaum, who uses a third definition, the spending will reach more than $352 million. To the list of accountability expenditures, Gotbaum would add periodic assessments, which cost the DOE more than $26 million during the last school year, according to the IBO report.

The DOE requires schools to conduct periodic assessments in all schools, but the tests are not used to evaluate schools or students. The DOE’s Office of Accountability administers the periodic assessments, and Schools Chancellor Joel Klein has described the assessments as an important component of his accountability initiative.

The DOE successfully made the case to the IBO that the assessments shouldn’t be considered part of the accountability initiative because they are “no stakes,” the IBO report includes a half-page discussion of the assessments’ cost. “We did think it was an important and large enough element of the education department’s Office of Accountability to leave it in the report,” Turetsky told me.

Turetsky said the whole process would have been easier were the IBO not so dependent on the DOE for information about its spending. Because the DOE is not officially a city agency, it is not required to comply with IBO requests, and at first it offered only “sporadic answers” to the IBO’s questions, he said.

Gotbaum’s Commission on School Governance this fall recommended that the IBO be given oversight of DOE data if the State Assembly mayoral control is preserved next year. “There is nowhere else to get this data,” Gotbaum said today. “There is no system of checks and balances that any of us has access to.”