The 2014 exodus of six suburban towns from the newly consolidated Memphis school system is one of the nation’s most egregious examples of public education splintering into a system of haves and have-nots over race and class, says a new report.

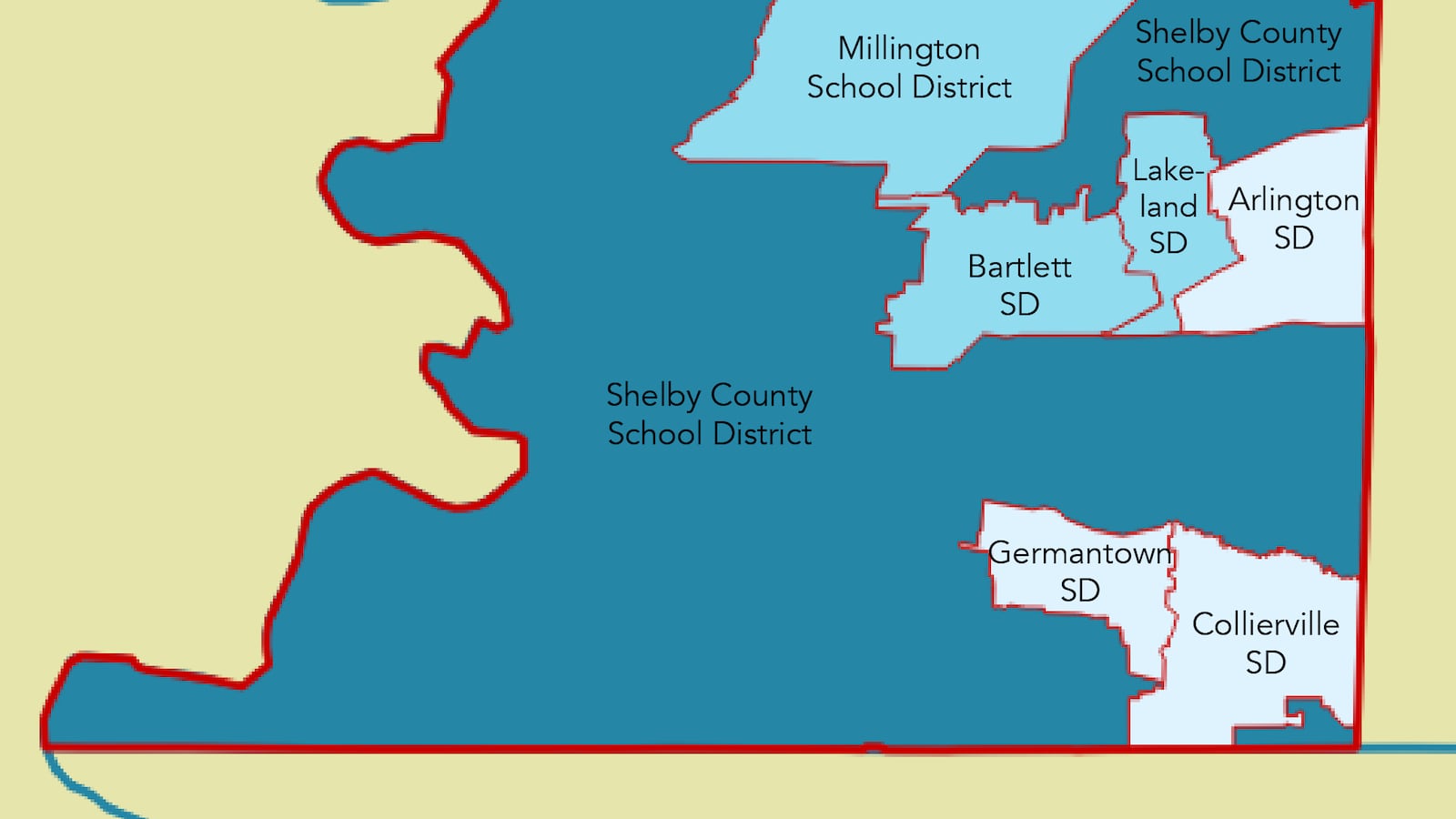

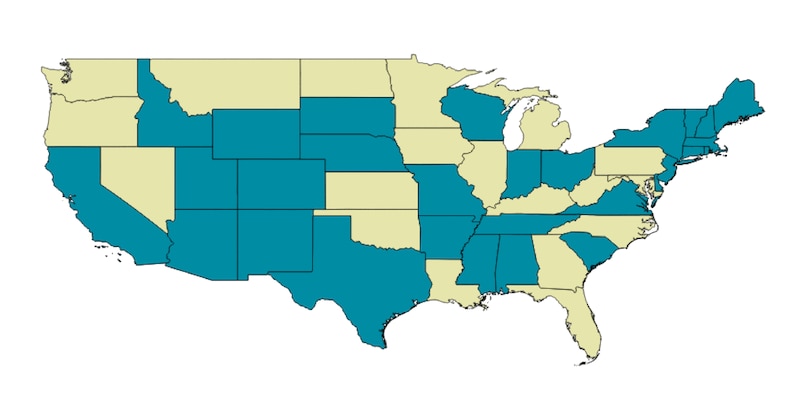

The Shelby County towns are among 47 that have seceded from large school districts nationally since 2000. Another nine, including the town of Signal Mountain near Chattanooga, Tenn., are actively pursuing separation, according to the report released Wednesday by EdBuild, a nonprofit research group focusing on education funding and inequality.

EdBuild researchers said the growing trend toward school secession is cementing segregation along socioeconomic and racial lines and exacerbating inequities in public education.

And Shelby County is among the worst examples, they say.

“The case of Memphis and Shelby County is an extreme example of how imbalanced political power, our local school-funding model, and the allowance of secession can be disastrous for children,” the report says.

After the 2014 pullout, Shelby County Schools had to slash its budget, close schools under declining enrollment, and lay off hundreds of teachers. Meanwhile, the six suburban towns of Arlington, Bartlett, Collierville, Germantown, Lakeland and Millington have faced challenges with funding and facilities as they’ve worked to build their school systems from the ground up.

The report says Tennessee’s law is among the most permissive of the 30 states that allow some communities to secede from larger school districts. It allows a municipality with at least 1,500 students to pull out without the approval of the district it leaves behind or consideration of the impact on racial or socioeconomic equity.

“This isn’t a story of one or two communities. This is about a broken system of laws that fail to protect the most vulnerable students,” said EdBuild CEO Rebecca Sibilia. “This is the confluence of a school funding system that incentivizes communities to cordon off wealth and the permissive processes that enable them to do just that.”

The Shelby County pullout is known in Memphis as the “de-merger,” which happened one year after the historic 2013 merger of Memphis City Schools with the suburban county district known as Legacy Shelby County Schools. The massive changes occurred as a result of a series of chess moves that began in 2010 after voters elected a Republican supermajority in Tennessee for the first time in history.

Under the new political climate, Shelby County’s mostly white and more affluent suburbs sought to establish a special school district that could have stopped countywide funding from flowing to the mostly black and lower income Memphis district. In a preemptive strike, the city’s school board surrendered its charter and Memphians voted soon after to consolidate the city and county districts. The suburbs — frustrated over becoming a partner in a consolidated school system they didn’t vote for — soon convinced the legislature to change a state law allowing them to break away and form their own districts, which they did.

Terry Roland, a Shelby County commissioner who supported the pullouts, said the secession wasn’t about race, but about having local control and creating better opportunities for students in their communities. “There are a lot of problems in the inner city and big city that we don’t have in municipalities in terms of poverty and crime,” Roland told Chalkbeat on the eve of the report’s release. “We’re able to give folks more opportunities because our schools are smaller.”

The report asserts that money was at the root of the pullouts. Through taxes raised at the countywide level, suburban residents were financially supporting Memphis City Schools. The effort to create a special school district was aimed at raising funds that would stay with suburban schools and potentially doing away with a shared countywide property tax, which would have been disastrous for the Memphis district.

"These policies are still relatively new in Tennessee. But I think a tsunami is coming as a result."

Rebecca Sibilia, CEO, EdBuild

“What we’re talking about here is the notion of people pulling out of a tax base that’s for the public good,” Sibilia said. “That’s akin to saying you’re not going to pay taxes for a library because you’re not going to use it. … You can see this as racially motivated, but we found it was motivated much more by socioeconomics.”

The report asserts that funding new smaller districts is inefficient and wasteful.

The United States spends $3,200 more on students enrolled in small districts (of fewer than 3,000 students) than on the larger districts (of 25,000 to 49,999 students), according to the report. Small districts also tend to spend about 60 percent more per pupil on administrative costs.

Under Tennessee’s current law, Sibilia believes the Shelby County de-merger is only the first of more secessions to come. She notes that Tennessee’s law is similar to one in Alabama, where a fourth of the nation’s secessions have occurred. Already in Chattanooga, residents of Signal Mountain are in their second year of studying whether to leave the Hamilton County Department of Education.

“There’s a direct link between very permissive policies and the number of communities that take advantage of them,” Sibilia said. “These policies are still relatively new in Tennessee. But I think a tsunami is coming as a result.”

Editor’s note: Details about the merger-demerger have been added to this version of the story.