The residents filing into the auditorium of Sharon Christa McAuliffe Elementary School Friday wanted to know a few key things from the eager aldermanic candidates who were trying to win their vote.

People wanted to know which candidates would build up their shrinking open-enrollment high schools and attract more students to them.

They also wanted specifics on how the aldermen, if elected, would coax developers to build affordable housing units big enough for families, since in neighborhoods such as Logan Square and Hermosa, single young adults have moved in, rents have gone up, and some families have been pushed out.

As a result, some school enrollments have dropped.

Organized by the Logan Square Neighborhood Association, Friday’s event brought together candidates from six of the city’s most competitive aldermanic races. Thirteen candidates filled the stage, including some incumbents, such as Aldermen Proco “Joe” Moreno (1st Ward), Carlos Ramirez-Rosa (35th Ward), and Milly Santiago (31st Ward).

They faced tough questions — drafted by community members and drawn at random from a hat — about bolstering high school enrollment, recruiting more small businesses, and paving the way for more affordable housing.

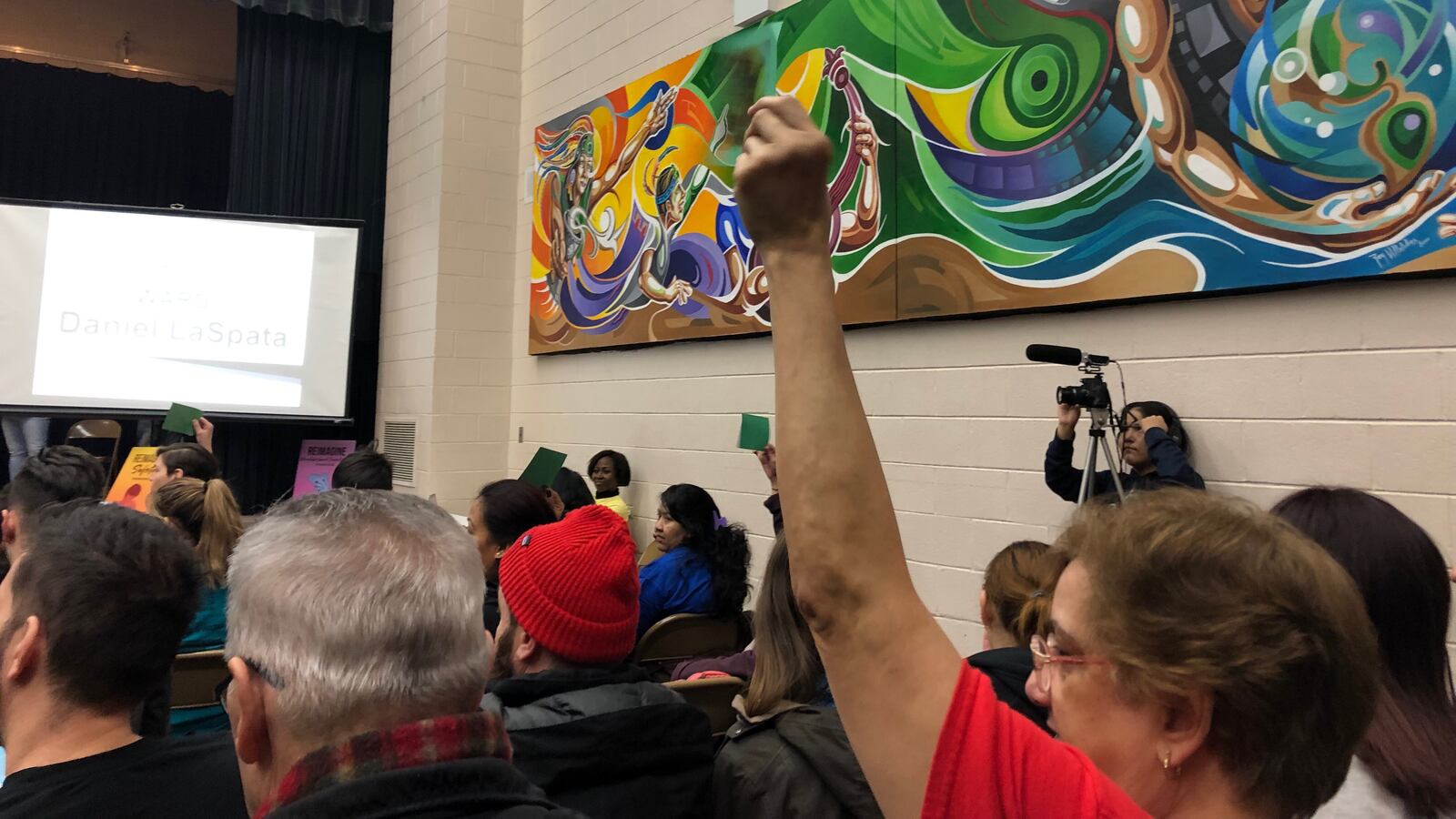

When the audience members agreed with their positions, they waved green cards, with pictures of meaty tacos. When they heard something they didn’t like, they held up red cards, with pictures of fake tacos.

Red cards weren’t raised much. But the green cards filled the air when candidates shared ideas for increasing the pull of area open-enrollment high schools by expanding dual-language programs and the rigorous International Baccalaureate curriculum.

Related: Can a program designed for British diplomats fix Chicago schools?

“We want our schools to be dual language so people of color can keep their roots alive and keep their connections with their families,” said Rossana Rodriguez, a mother of a Chicago Public Schools’ preschooler and one of challengers to incumbent Deb Mell in the city’s 33rd Ward.

Mell didn’t appear at the forum, but another candidate vying for that seat did: Katie Sieracki, who helps run a small business. Sieracki said she’d improve schools by building a stronger feeder system between the area’s elementary schools, which are mostly K-8, and the high schools.

“We need to build bridges between our local elementary schools and our high schools, getting buy-in from new parents in kindergarten to third grade, when parents are most engaged in their children’s education,” she said.

Sieracki said she’d also work to design an apprenticeship program that connects area high schools with small businesses.

Green cards also filled the air when candidates pledged to reroute tax dollars that are typically used for developer incentives for school improvement instead.

At the end of the forum, organizers asked the 13 candidates to pledge to vote against new tax increment financing plans unless that money went to schools. All 13 candidates verbally agreed.

Aldermen have limited authority over schools, but each of Chicago’s 50 ward representatives receives a $1.32 million annual slush fund that be used for ward improvements, such as playgrounds, and also can be directed to education needs. And “aldermanic privilege,” a longtime concept in Chicago, lets representatives give the thumbs up or down to developments like new charters or affordable housing units, which can affect school enrollment.

Related: 7 questions to ask your aldermanic candidates about schools

Aldermen can use their position to forge partnerships with organizations and companies that can provide extra support and investment to local schools.

A January poll showed that education was among the top three concerns of voters in Chicago’s municipal election. Several candidates for mayor have recently tried to position themselves as the best candidate for schools in TV ads.