In an unusual step, Colorado’s top school improvement officer warned in a letter to Aurora Public Schools officials that his office is looking for “decisive and bold actions” to improve the city’s chronically struggling high school, Aurora Central.

The letter, sent Monday, comes as teams of students, teachers, parents and community members are working feverishly to submit plans to the state they believe will improve five academically struggling schools — including Central.

The Aurora community is likely going to get its first look at those plan next year. Schools are in the process of vetting their plans and building consensus among their respective communities.

Peter Sherman, the Colorado Department of Education’s executive director of school and district performance, said his letter is meant to give the Central community guidance in crafting a plan his office can support before the State Board of Education.

“We’d like to engage with the district along the way so when we get to the finish line we all believe we have a plan that will have an impact on student learning,” he said in an interview.

But if the Aurora-grown plan to improve its schools doesn’t satisfy those conditions, the education department is prepared to ask the State Board of Education to reject Aurora’s bid to win waivers from state law and possibly impose sanctions instead, Sherman said.

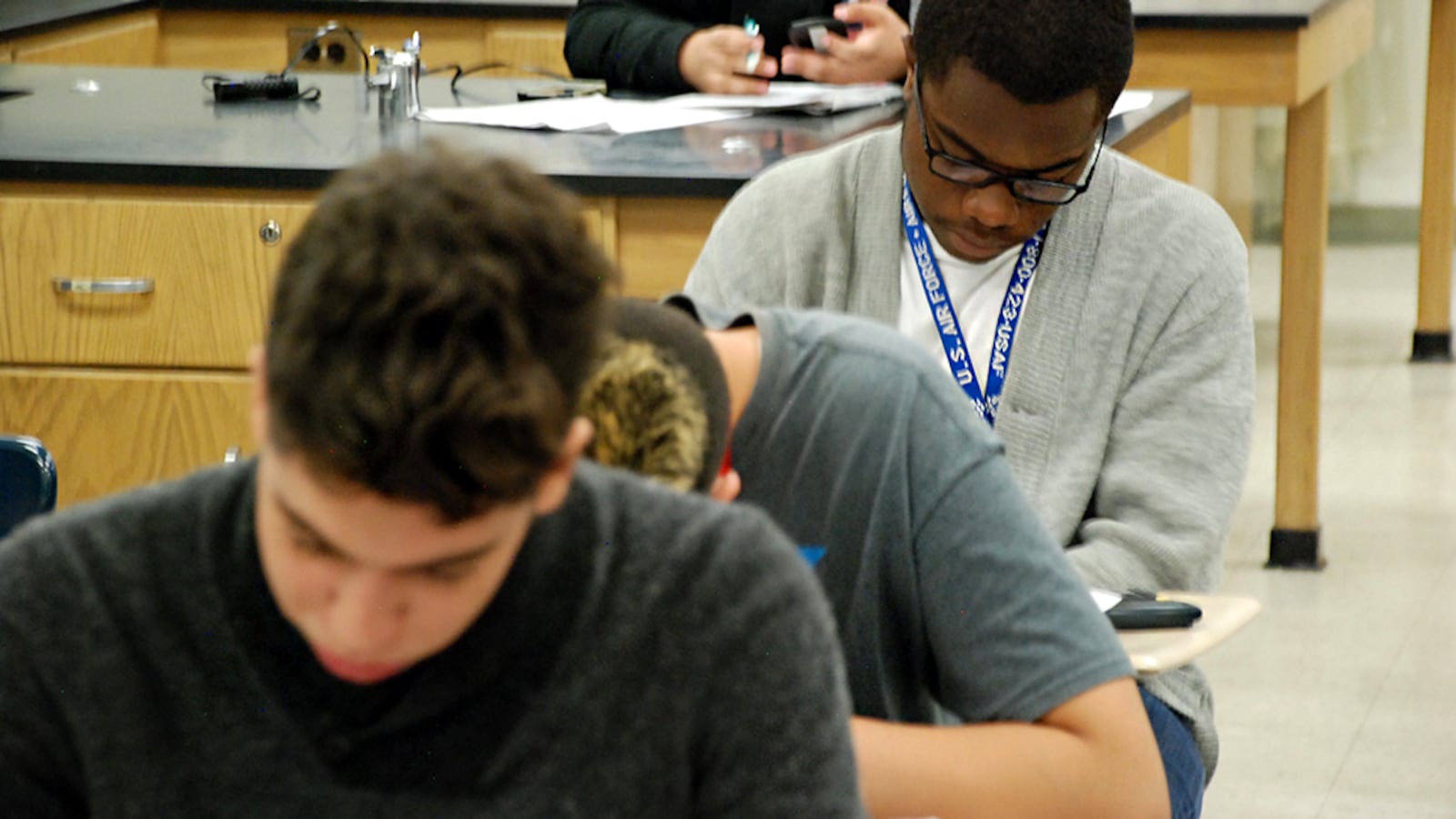

More than a dozen schools in Aurora, the state’s fifth largest school district, are on the state’s watch list for poor academic performance. The school district as a whole also dramatically falls short on state tests. And fewer students — most of whom are poor, Latino and black — graduate each year compared to peers in surrounding districts.

Aurora is in danger of losing its accreditation if student learning doesn’t pick up.

To boost student learning and stave off state sanctions, Aurora Superintendent Rico Munn has proposed a cluster of schools be allowed to craft their own calendars, budgets, hiring policies and curriculum.

This flexibility can be provided under the state’s school innovation laws if a majority of parents, teachers and students approve of the plan — and if the local school board and State Board of Education sign off on it.

Multiple committee formed this fall to begin work on the innovation plans. The district hired the education nonprofit Mass Insight for $600,000 a year to schedule meetings, coordinate research and draft proposal language.

One committee in charge of developing a curricular and cultural theme for the five schools — Boston K-8, Central High, Crawford and Paris elementaries, and West College Prep Academy — chose “international leadership.”

It’s unclear how that theme will play out at each school. That’s something other committees will figure out.

Four schools in Denver use the same model, with mixed results. While those schools serve similar student demographics, the schools in Aurora are much larger.

Dan Lutz, the founding principal of the Denver Center for International Studies schools, told an audience of Aurora parents at a meeting in October that the theme must take hold in the classroom.

“If you really want to make a difference, it has to start with the classroom and the teachers and how students learn,” Lutz said.

Committee members who helped select the theme said it was an easy decision given Aurora’s extreme diversity, which includes a large population of refugee and immigrant students.

“This theme says we recognize that we’re different and that we celebrate it,” said committee member Maisha Fields, executive director of the Fields Foundation. “And as we prepare children for a global economy it is really about understanding culture.”

Fields and others said specific details are still scarce, but she hopes a priority for the schools will be to recruit a more diverse teaching staff.

“We’ve heard from the community that they want to learn from people who look like them,” she said.

Central High English teacher Shari Summers said part of the effort includes researching how schools around the world recruit and retain diverse teaching staffs.

“We’re moving along,” she said. “I’m most excited for our kids. We have the opportunity to do really cool things.”

But Summers and others cautioned that while there is momentum, the approved plans will be rolled out over three years.

“We don’t want it to be an overwhelming process for anyone,” Summers said. “[But] we’re moving faster than I anticipated.”

Still, the state department of education believes drastic changes must be made at Central, especially after the school failed to execute a plan to improve the school that was financed by a $2.7 million federal grant awarded in 2013.

“There’s not enough improvement fast enough,” Sherman said.

In his letter, Sherman recognized that student attendance at Central had improved.

But students felt that classroom culture and expectations were inconsistent and low. He also highlighted that the school had several essential staff positions to fill after the start of the school year. And several current teachers aren’t receiving training outlined in the school’s grant proposal.

Sherman said he is optimistic about the school’s new principal, Gerardo De La Garza, and the potential reboot innovation status can provide the school.

“The grant money can help,” he said, “but what’s foremost to improve is the conditions the school is operating in.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article reported that a district deadline to review school innovation plans was pushed back. That information was provided by a district consultant. There was no such deadline, the district says.