NaTasha Montoya nearly gave up on working in the classroom. She spent five years as an elementary paraprofessional who also coached junior high girls basketball and worked an after-school tutoring gig, and she still only earned $19,000 a year — so she took a job as a shipping manager for a local firm in Rocky Ford, the southeast Colorado town where she has lived most of her life.

Montoya sometimes thought about going back to school to become a teacher — she already had an associate degree from nearby Otero Junior College — but she didn’t know how to even start that process, and she didn’t want to relocate to a larger city where she didn’t know anyone.

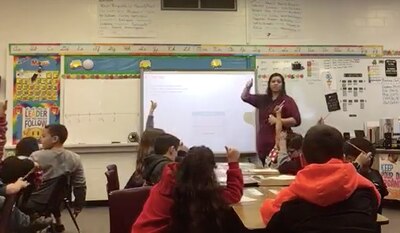

Montoya is now a newly licensed elementary teacher with a third-grade teaching job lined up in her hometown for this fall, one of the first three students to graduate from a new University of Colorado Denver program that partners with local community colleges, starting with Otero Junior College in La Junta.

“I’ve learned so much about my career and about myself and how I can help my kids be successful in their lives,” Montoya said. “Talking to people who went through other teaching programs, I think I got the full package.”

By making high-quality educator preparation programs available in rural communities and recruiting candidates from those communities, administrators hope they can make a real dent in the teacher shortage. Students who come in with an associate degree can earn a University of Colorado Denver bachelor’s degree without leaving Otero County. Nearly two dozen more early elementary teachers are expected to graduate from the program in the next two years, and CU Denver plans to offer programs for those who want to teach middle school math and secondary science — areas of severe need — starting next year. The program will also expand to a second junior college in Trinidad, near the New Mexico border.

“Many of our students are working students with really deep roots in the community,” said Barbara Seidl, associate dean for teacher education and undergraduate experiences at CU Denver. “We believe that people who are from a rural community are more likely to stay and teach and lead across an entire career. We hope it will have a significant impact.”

Like many states, Colorado is grappling with a teacher shortage that is particularly acute in rural areas and in specialties like science, math, and special education. Lawmakers have funded new programs to provide stipends and fellowships to rural teachers who are starting their careers or pursuing additional education. The most generous of these provides up to $25,000 in loan forgiveness for teachers who stay in their districts for five years.

As much as rural districts struggle with recruitment, it can be even harder to keep teachers, given the low pay and the geographic isolation. Recent graduates who take a first teaching job in a rural area often leave for higher-paying jobs in larger towns once they have a few years of experience. Across the country, states and districts are investing in “grow your own” approaches that help young people from rural communities enter the teaching profession.

This isn’t the first time this approach has been tried in Colorado. Adams State University, a four-year institution some 150 miles away in Alamosa, used to partner with Otero Junior College. That program was discontinued when the grant that funded it expired, though Adams State continues to educate many teachers who go on to work in rural schools in the surrounding San Luis Valley, and offers an online teaching degree to students who already have an associate degree.

The economics of the new program presented a challenge for both institutions, Seidl said. They wanted to offer a high-quality program that would serve a small number of students with enrollment that might be a handful one year and a dozen the next.

Seidl said she believes they have a sustainable financial model. Nonetheless, “we shifted resources to do it. It’s a real investment.”

Students use online meeting software to join classes in Denver, take some classes online, and work with local instructors for others. The final year includes a residency, in which students get classroom experience under the close mentorship of an experienced teacher in the area. Seidl said building local capacity and experience was another priority, and both institutions worked closely with area school districts to ensure that graduates meet their needs. Veteran educators also received training in how to support student teachers.

“The quality of what we’re providing is equal to the quality of the program we offer in Denver,” Seidl said. “It’s a wonderful, strong, rigorous program that has deep clinical experiences throughout. The last year is a full residency in a school. Students have hundreds of hours of classroom experience before they graduate.”

Ashley Morlan, a third-grade teacher at Jefferson Intermediate School in the Rocky Ford school district, is an adjunct professor in the program and supervised Montoya during her student teaching. She’s a local herself — educated through the Adams State program — and she sees some real benefits to hiring home-grown teachers.

Known around the state for its sweet melons, Rocky Ford struggles with poverty and all the challenges that come with it. Median household income is $32,000 a year, and almost 80 percent of the district’s 760 students qualify for subsidized lunches.

Outsiders sometimes find the town, with fewer than 4,000 residents, to be insular. Morlan said many teachers who leave say they found it hard to make connections. But locals already have those connections.

Montoya said that was the case for her.

“I grew up in the community,” Montoya said. “If I don’t know someone directly, I know their cousin or their aunt or their older sibling. It’s easy to find a connection with the kiddos.”

On Saturday, Montoya came to Denver to walk across the stage in her cap and gown — becoming the first college graduate in her family — and next year she’ll be teaching third grade at Jefferson Intermediate School, alongside Morlan.

While the long-term effects of the program remains to be seen, Morlan said it’s already making a difference, one teacher at a time.

“To me, it’s already made an impact because NaTasha now teaches third grade with me,” she said. “If it weren’t for her, who knows who would have filled that position?”