In a year when a few states posted across-the-board gains, New York State saw limited progress on the test known as “the nation’s report card,” according to new data released today about the 2013 tests.

Only fourth-grade math scores saw a statistically significant increase on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, an assessment given to fourth- and eighth-graders across the country every two years. New York students’ scores in fourth-grade reading, eighth-grade reading, and eighth-grade math showed no significant changes from 2011.

That’s a better result than the scores two years ago, when New York was one of just two states to post significant declines. (New York City’s scores outpaced the rest of the state slightly.)

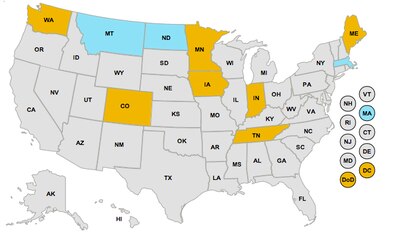

Across the country, Tennessee, Hawaii, and the District of Columbia saw the biggest gains across both grades and subjects, though scores for Washington, D.C. especially still rank among the nation’s lowest.

“You’d like to see some steady improvement across subjects, though generally seeing an increase in all subject-grade combinations is very rare,” said Jack Buckley, the commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which administers the NAEP. “It’s hard to move the needle on all four grades and subjects unless you’re really doing something.”

But he cautioned that the numbers themselves don’t point to specific successes. “There will be a flurry of people taking credit for their favorite policy and blaming their least favorite policy for why their scores didn’t go up,” he said.

Indeed, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan suggested that Tennessee and D.C. in particular had succeeded because of their “laser-like focus on teacher effectiveness” and rapid shift to new standards known as the Common Core. Duncan made adopting common standards and new teacher evaluations that weigh student performance a requirement for winning federal Race to the Top funds in 2010. Tennessee was one of the earliest winners, and D.C. joined New York in a second pool of grant recipients.

Duncan also emphasized that none of the first eight states to adopt Common Core standards saw statistically significant score decreases between 2009 and 2013 — though many of those states didn’t see see increases, either.

He attributed the variations among states to what he called “extraordinary leadership” at the state level, from officials who have “done some very difficult and courageous work” raising standards. He added, “Where people are more timid, you’re seeing less progress.”

Eric Hanushek, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University, said the NAEP results validate the pace of change in Tennessee and D.C.

“That’s why this is so significant — there was huge pushback, particularly from current school personnel who liked the way things were going,” Hanushek said. “You wouldn’t want to get into a fight if it had no impact. But in fact — the improved performance is something that they should be proud about.”

Hanushek said the overall picture remained discouraging, with scores across the country improving less quickly than they have in the past.

Two years ago, New York State Education Commissioner John King said New York’s NAEP scores would increase once planned policy changes went into effect. The state’s first round of Common Core-aligned tests was last spring, after the most recent NAEP administration. And teachers in most of the state only recently got their first ratings that consider student performance; teachers in New York City won’t be evaluated that way until after this year.

“The scores on this NAEP report underscore a tough but necessary truth: Our students are not where they should be,” King said in 2011. “The reforms we’re implementing will help get them there.”

Some of the national results bucked recent trends. In the past, much of the score increases have been attributed to the lowest-performing students catching up with their peers. This year, Buckley noted that a big chunk of states’ gains came from high-performing students pulling further ahead. Gains have also been more common historically at the fourth grade level, but this year it was eighth-grade reading that improved most.

For years, NAEP has been the only way to compare student performance across states with vastly different standards for their own tests. But Buckley argued that the tests will remain relevant even as more states align their tests to common standards, given how many variations remain and the importance of NAEP’s long-term data collection.

“If everything is changing, we’re going to be the only time series people can use to make comparisons,” Buckley said.

New York City’s local results will come out in December along with data from other urban school districts. In the past, the city’s state test score gains have outpaced the state’s, but it would be hard for NAEP scores statewide to shift one way if the city’s scores moved the other way, given the city’s population.

Jaclyn Zubrzycki contributed reporting.