This is part of an ongoing collaborative series between Chalkbeat and THE CITY investigating learning differences, special education and other education challenges in city schools.

One school bus kept a 5-year-old autistic boy on board for three hours.

Another yellow bus carrying a 13-year-old with autism took a wrong turn and ended up in New Jersey.

A third bus had been slated to take an 11-year-old boy with Down syndrome to his former elementary school in Long Island City on the first day of school, rather than to his new middle school across Queens in Corona.

These are just a sliver of the headaches that dozens of parents of children with special needs say they’ve endured already this school year under a busing system that, as the data shows, has been getting worse.

Over the first 24 days of this school year, 12,060 yellow buses transporting special needs kids were delayed on the way to or from school — an average of about 500 per day, according to an analysis of Office of Pupil Transportation data conducted by THE CITY.

Daily delays are up 5% from the same period the year before — and are nearly twice the 280 delays per day at the beginning of the 2015-16 school year.

Overall, special education busing delays, self-reported by the yellow bus companies, nearly doubled over the past five years from 44,279 to 80,765, the data show.

Education officials noted the number of special education routes has also increased in recent years, growing by nearly 500 over the past two school years — to 5,733.

The vast majority of delays were attributed to heavy traffic, while others were blamed on flat tires, mechanical problems and “other” issues, according to online OPT records.

But some parents of the roughly 50,000 special needs students who rely on yellow buses in the city say the problems only start with punctuality and interminable rides — extending to missed class time, humiliating bathroom accidents, and bullying or assaults.

“It’s a broken, broken system that offers no protection for children whatsoever,” said Anne Kanable, the mother of the 11-year-old, Dane, who would have ended up at his previous school if his mother hadn’t intervened.

Kanable spent the first two weeks of the school year fighting to get Dane a bus to the right school, as well as a better route to his after-school program with a shorter travel time than 2 hours and 40 minutes.

In past years, Dane has come home with unexplained scratches and bruises on his body, and was out of contact for five hours during one ride, his mother said. Kanable has filed as many as 18 complaints with OPT in a given year, she said.

“I don’t feel safe every single day,” said Kanable. “I’m always waiting for the next issue to happen honestly. It’s sad, it’s very sad.”

Parents like Kanable are expected to air their busing frustrations Thursday at a Citywide Council on Special Education meeting at 6 p.m. at Department of Education headquarters at 52 Chambers St.

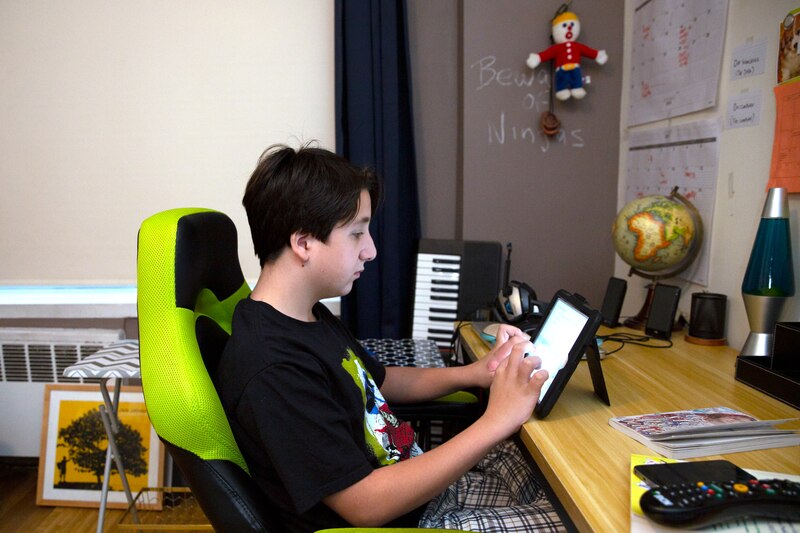

West Village mom Bunny Rivera has seen bus-related frustrations mount daily for herself and her 13-year-old son Chazz, a student at Lower Manhattan Community Middle School who’s on the autism spectrum and is challenged by attention deficit disorder.

The first few days of school, Chazz didn’t take the bus because it never showed or arrived several hours late. On a trip home from school, the bus moved two miles in two hours, forcing Chazz to miss a therapy appointment that Rivera still had to pay for, she said.

When Chazz finally took his first morning bus ride eight days into the school year, the vehicle got into a minor accident and arrived at school an hour after classes started, Rivera said. The next morning, the eighth-grader’s bus driver ended up mistakenly taking the Holland Tunnel to New Jersey.

“My son was freaking out. He was terrified he was being kidnapped,” recalled Rivera, whose son used his cell phone to call her during the ordeal.

Rivera has been supplementing her son’s commute by hailing Ubers and sending the bills to the Department of Education for reimbursement.

“I said ‘He’s going to take an Uber the rest of the year, and you’ll pay for it,’” Rivera said. “Within two days [his route] got straightened out.”

While the Office of Pupil Transportation has been the target of parental ire for years, the agency came under heightened scrutiny last year when it hit a high for the number of buses that were delayed in September.

Two months later, the agency was faulted for not being able to tell some parents where their kids were for hours during a snowstorm that kept some kids on buses until the early morning.

Since being appointed in March 2018, city Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza has removed or reassigned a number of top officials in charge of the $1.3 billion yellow bus system. Just weeks ago, he terminated director of pupil transportation Alexandra Robinson.

She was singled out in a recent probe by school investigators for her mismanagement of a GPS system that had been introduced in 6,000 of the city’s roughly 9,500 yellow buses in recent years — but was ineffective because most drivers didn’t log into the devices.

Robinson had been slated to speak to parents at a Thursday’s meeting. With her departure, senior advisor to the chancellor Kevin Moran will now address — and listen to — parents on busing, education officials said.

Department of Education officials said special education routes are more likely to be delayed than general education routes because they tend to be longer, and often cross school district lines. They said that 64% of delays are attributed to heavy traffic.

“We continue to see a decrease in calls year over year, and remain committed to improving service for students and families,” said Miranda Barbot, a DOE spokesperson.

Education officials have also been hailing their latest GPS efforts as a stress reliever for families that will also help create smarter bus routes. But they’ve been unclear on the timeline for rolling out the system, which will, for the first time, provide parents access to real-time GPS information.

The technology was mandated by the start of this school year under a City Council law passed in January. GPS systems were installed in every bus that didn’t previously have one. But the devices don’t give families the ability to track their child’s bus as required.

DOE officials told THE CITY and Chalkbeat that the new GPS system, under a contract with the ride-sharing firm Via, won’t be used until January 2020 — and only on a “small set of buses” to start.

They said full installation will be completed “before the start of next school year.”

“Through route optimization with Via, we will see a decrease in traffic delays — which account for the majority of delays across the system,” said Barbot.

For the time being, however, GPS problems “continue to reverberate” across the yellow bus system because they still rely on drivers to log in — something that’s not required under current contracts, according to the report by school investigators.

“These devices merely ping a position of a bus — locations which can prove unreliable — and relies upon drivers interfacing with the devices,” the report said. “These are the same issues that have plagued the GPS project since its inception.”

Additional reporting by Ann Choi.