New York City’s Pre-K for All initiative is truly a delightful, play-based program based on developmentally appropriate practices for young children. I know this well because for two years, I was a consultant for the city’s education department making sure that pre-K classes were high-quality and joyful places.

As a program evaluator from 2016 to 2018, my job was to visit pre-K classrooms to make sure that they adhered to guidelines set forth in the two assessment tools that the city is using to measure program quality.

Part of that work involved listening to conversations between teachers and children and assessing the classroom culture. Did children frequently laugh and smile? Did teachers respond to children’s needs sensitively?

I would also check if programs were providing the children with ample materials devoted to art, music, block play, dramatic play, physical education, and math and science — materials that children could use independently in open-ended ways, not just as directed by a teacher.

And one very important aspect of my work was calculating the number of minutes in each program devoted to unstructured play. The city requires programs using education department funding to allocate one-third of the school day to unstructured play — two hours and seven minutes a day of free play in a standard, full-day program. Programs that fell short would get dinged in the reports I wrote after each visit.

I left this role and took on a kindergarten teaching position not far from New York City, in Nassau County on Long Island, after two years. What I saw and experienced as a kindergarten teacher shocked me as I learned firsthand that kindergarteners in my school spent very little time engaging in any form of free play. Additionally, my classroom looked almost nothing like what I used to see in pre-K classrooms, though the children were only a year older. Gone were the blocks, the dramatic play center, the sand table, and almost every type of manipulative that typically fills a pre-K classroom.

Instead of watching children engage in explorative, self-directed play, our days were filled with one teacher-directed lesson after another mostly focusing on phonics, literacy, and math. Some of the children could not hold a pencil properly or did not yet know the alphabet but were expected to complete curriculum-driven worksheets frequently. I had to give my kindergarteners sight word quizzes on a weekly basis and perform standardized reading-level assessments several times during the school year. Children, who are designed to move and wiggle and squirm, were expected to sit still for long periods of time either on the carpet or at their desks. And whereas New York City pre-K programs mandate physical education on a daily basis, my students only experienced it three times a week. (My son, who had entered kindergarten at the same time in a different school, only had physical education twice a week.) It was hard for me to follow these strict school-based mandates that went against what I knew was best for children, but while my immediate supervisor agreed with me to a large degree, there was little we could do.

My experiences as a kindergarten teacher are not unique. A 2009 report by play advocates found that many New York City kindergartens offered little time for free play and were devoid of materials such as blocks, dramatic play props, and sand and water tables. More recently, a 2016 study concluded that kindergarten had indeed become “the new first grade” in terms of the academic skills expected of students.

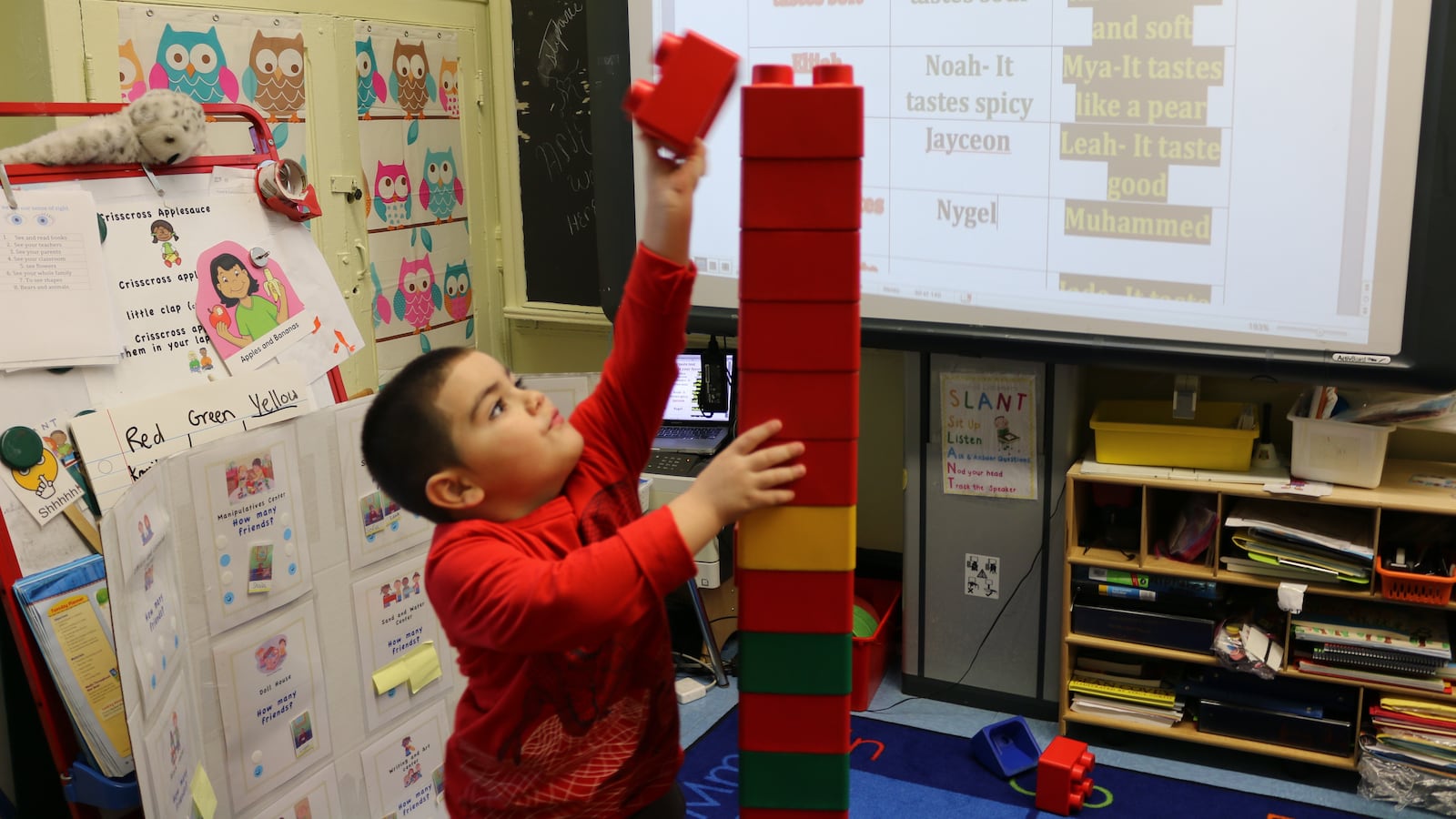

Recent research has found that the changes to kindergarten have not been bad for students’ learning or their emotional development. Yet like so many other educators, I know firsthand the power of what happens during unstructured time. Observing pre-K classrooms, I saw that when children play “store,” they learn about counting, money, and simple addition or subtraction. When children are given time and access to materials that encourage expressive language such as human and animal figures, puppets, dolls and pretend telephones, they are communicating with their peers and their teachers, developing crucial language skills that are an important precursor to early literacy. And when children build LEGO towers or large “cities” with wooden blocks, they are developing spatial, math, and problem-solving skills, not to mention fundamental social skills such as sharing and working together.

I could see that by replacing these activities with worksheets and Smartboard presentations, I was depriving my students of opportunities for joyful learning — and I knew that their options to make up the play time were limited. A good portion of my kindergarten children were from immigrant families and from low-income households. They arrived at school at 7:30 a.m. to eat breakfast and did not go home until well into the evening, having gone to after-care or academic support programs directly after the school day ended. Most lived in apartment buildings without backyards or access to nearby playgrounds, limiting outdoor play. Some said that they had few toys at home, besides the iPads that they cited as a main form of entertainment. I quickly realized that unless children experienced free play in my classroom, many would not at any time during the day.

There was no designated time in the daily schedule for free play at all, but sometimes I would sneak in choice time during the day where kids got to play freely with puzzles, math manipulatives, and building toys. It was during these moments that I would see my students’ eyes light up as they were finally able to exercise some agency.

But no teacher should have to do what they think is best for his or her students secretly, behind closed doors. I wished that my school administrators understood what I had seen: that play is far from frivolous; with training, educators can encourage discovery, experimentation, and creativity in kids; and laughter is the sound of children learning.

Farah Akbar is a former classroom teacher and Pre-K program evaluator. She is currently a freelance writer.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.