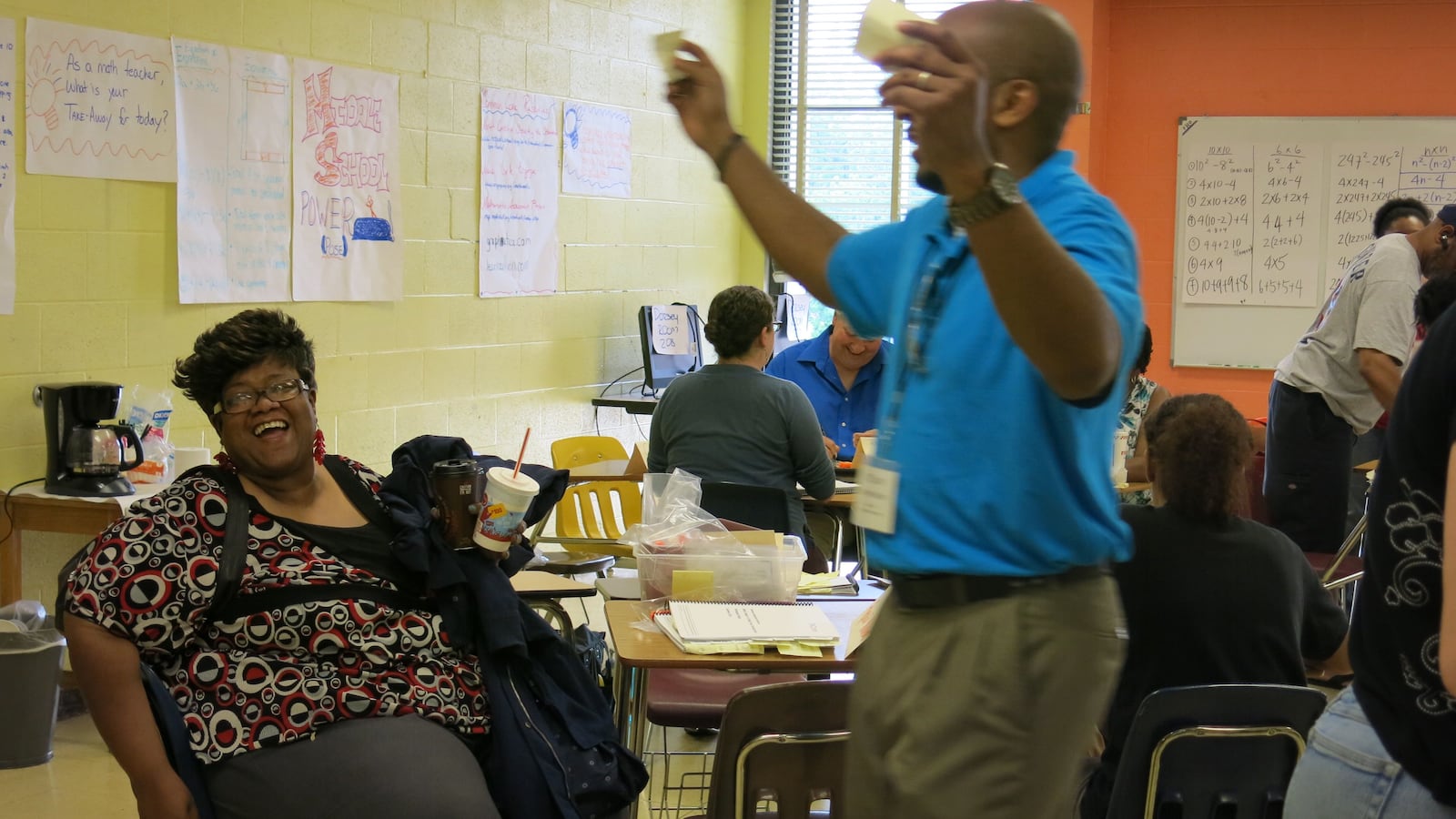

Renia Williams waved her blue-painted finger nails in the air at a training in Memphis last week as she shared her classroom experience teaching Common Core with fellow middle school teachers.

“Common Core is forcing kids to think,” she said, eliciting finger snaps from the other teachers in the room, like at a poetry jam.

Williams is an eighth grade teacher at Treadwell Middle School in Memphis. She was one of 187 teachers trained at Ridgeway High School last week as “learning leaders,” who will go back to their own schools and train other teachers how to teach Common Core standards. About 14,000 teachers in all will be trained in sessions held by the state department of education this summer at 40 sites across the state.

Common Core is a series of baseline reading and math standards Tennessee adopted in 2010 that determine what children should learn in each grade. Unlike standards used in the past, Common Core emphasizes that students build critical thinking, creativity and problem-solving skills that often require a different style of teaching. Instead of children calculating math problems and presenting their answer, for example, they instead must now show how they arrived at their answer.

Initially adopted in 46 states and the District of Columbia, the standards have been subject to political controversy in recent years, with many states passing laws that have repealed or weakened their impact. This past spring, the Tennessee General Assembly voted to delay the use of PARCC, a national test designed specifically with the standards in mind.

Teachers have complained that the new standards come at a time of more pressure to boost test scores. They have pointed out that, with districts’ constrained budgets, professional development opportunities have decreased while standards have increased.

Last week’s training offered by the state department was geared toward providing teachers with pedagogy skills such as encouraging students who don’t pick up new skills right away or helping students organize their thoughts while preparing to write an essay.

The teachers did not receive compensation for attending the three-day training sessions. The department’s spokesperson, Ashley Ball, could not provide the cost of the summer trainings.

Williams considers teaching math her destiny. She had dreamed of being a math teacher from the age of four, inspired by a devoted kindergarten teacher and her late mother who was a math teacher. She opted out of more lucrative career options her engineering and computer science degrees proffered to go into the classroom.

Williams had been teaching for almost two decades when Tennessee first rolled out the Common Core standards as a way to boost student achievement.

She said she felt like she was good at her job, and already knew what her students needed to succeed without Common Core. The new standards seemed an unnecessary departure.

“At first I was reluctant to even deal with it,” she said. “They’ve been throwing Common Core out here, but not helping people realize where the pieces fit.”

But at the recent training, Williams displayed the zeal of the converted.

She said she has grown to appreciate the Common Core Standards after realizing that it helped her teach more like the teachers who had instilled her love of math, by connecting skills in the classroom to real-world problems. She said her “Aha!” moment came when she received her students’ TCAP scores after the first year of Common Core, and they had improved – despite the fact that she didn’t teach to the test at all.

This summer’s training made the state’s expectations and the national standards clearer.

The content of this summer’s trainings build on the learning from previous summers, but target the areas of greatest need for continued support, which department officials felt were writing and math, Ball said.

“Last year was to make sure teachers understood what the standards were,” said LaShanda Simmons, the site leader for training at Ridgeway and a literacy coach for Shelby County’s Innovation Zone, a cluster of schools that academically rank in the bottom 5 percent of the state. “Now, we can go deeper.”

During last week’s session, elementary English teachers practiced modeling essays for their students and were introduced to a writing strategy called Self-Regulated Strategy Development, for the first time. Teachers use the strategy to give students a “road map” of six stages, including various levels of planning, writing, and revision, that they can use to be successful writers.

Coaches in both the math and English sessions emphasized that harder work must be paired with a culture of encouragement.

“If [a student] sees all zeroes, he’s not going to fix anything,” a literacy coach told teachers. The coach urged the teachers in her session to find things to praise kids for, even when they’re struggling with reaching most standards.

The math teachers worked on a technique where students derive their own mathematical equations from word problems. At least three teachers volunteered that their students found the teaching method frustrating.

Williams said that the key to giving her students such difficult assignments was establishing that she believed they could do it. She attributes her students’ high TCAP scores to high standards and expectations. Talking about how to help guide her students through challenging math concepts was helpful, she said.

“Words can’t describe what I got out of the first day,” she said. “It made me realize we’re on the right path.”