When parent and longtime Binghampton resident Lee Evans heard about the plan last year to require students to take a test to enroll at the iconic East High School, he didn’t understand why that meant some students in the neighborhood could not attend.

Evans, an alumnus, worried they would drop out if they couldn’t attend East. He also worried the neighborhood would lose its longstanding connection with the school.

“You can’t throw the whole haystack away to find the needle,” he said in a recent documentary about years of changes in Binghampton schools.

Evans’ concerns have been echoed by others in the neighborhood. As the Memphis district creates new programs to improve academic performance and attract students, some parents, students and other members of the community worry that neighborhood students won’t benefit from the changes.

The historic school, in one of the most visible spots in Memphis along Poplar Avenue, is the epicenter of a model that Shelby County Schools leaders want to see replicated across the district — especially for long-neglected schools in impoverished neighborhoods. East High had dwindling enrollment and low test scores. To reverse the tide, district leaders replaced the school’s traditional curriculum with one focused on transportation.

In its first year, all freshmen were required to test to be admitted to East, which left some families worried they would not be eligible to attend. Neighborhood students who scored high enough were given priority.

Under new requirements this year, students enrolling in the diesel program will no longer have to submit test results, a move made to keep more neighborhood students at the school. They will need a C-average, a satisfactory behavior record, and fewer than 15 tardies or absences at their previous school. Studies have shown that students from low-income families often do not score well on standardized tests.

Students enrolling some components of the program, such as aviation, still will be required to take a test for admission.

The new admissions policy allowed most of the eighth grade students from Lester Prep, a neighborhood school in the state-run Achievement School District, to attend East High this year. Of the 125 freshmen this year, one-third live in the neighborhood, according to the district.

Concerns and skepticism remain

Yet even with this change, some observers are concerned.

Memphis created specialty programs, known as optional schools, in the 1970s to retain high-achieving and white students during school desegregation. But this is the first time Shelby County Schools has created an admissions process that caters to two different kinds of students for a single program.

Charles McKinney, who recently wrote a book about Memphis’ influence on the broader African-American struggle for equality, is still troubled by the message the admissions process sends.

“My vision would not include this first step of removing students currently in the building. In a really substantial way you’re saying you can’t build an excellent school unless you have high-achieving students. And that’s fundamentally flawed,” the Africana studies chair and history professor at Rhodes College told Chalkbeat. “The district’s job is to build educational excellence for all children regardless of their academic status.”

The new rules for entrance into East High School “are a step in the right direction,” he said. But if the district plans to replicate the model in other schools, the process should be more inclusive of students from poor families and students of color.

“The district is mostly black and brown kids, but those numbers aren’t reflected in these elite educational spaces,” McKinney said. “It’s not that those students don’t exist, it’s that we’ve added a number of significant barriers for students who are smart but happen to be from poor families.”

This isn’t the first school the district has restructured to attract more students. It is modeled after Maxine Smith STEAM Academy, a middle school that is expected to be a feeder school for East, about two miles away. The district closed Fairview Junior High School in 2013 and reopened the building as the new academy focused on science and technology and required all students to take a test as part of the admission process.

The result was a middle school that quickly became the most sought-after in the district and achieved some of the highest scores on state tests. The white student population grew to almost half and just 11 percent of students are from poor families. Before the transition, the former school had all black students and 92 percent were living in low-income households.

Lischa Brooks, East High’s executive principal who formerly led Maxine Smith STEAM Academy, said her continued leadership was contingent on the school including more students who may not be great “test takers” but otherwise would thrive in the new programs at East.

“Instead of lowering our expectations, we have people there every day to support our students,” said Brooks, a 1991 graduate of East High. “We’re going to show you can do it.”

Supporting the school

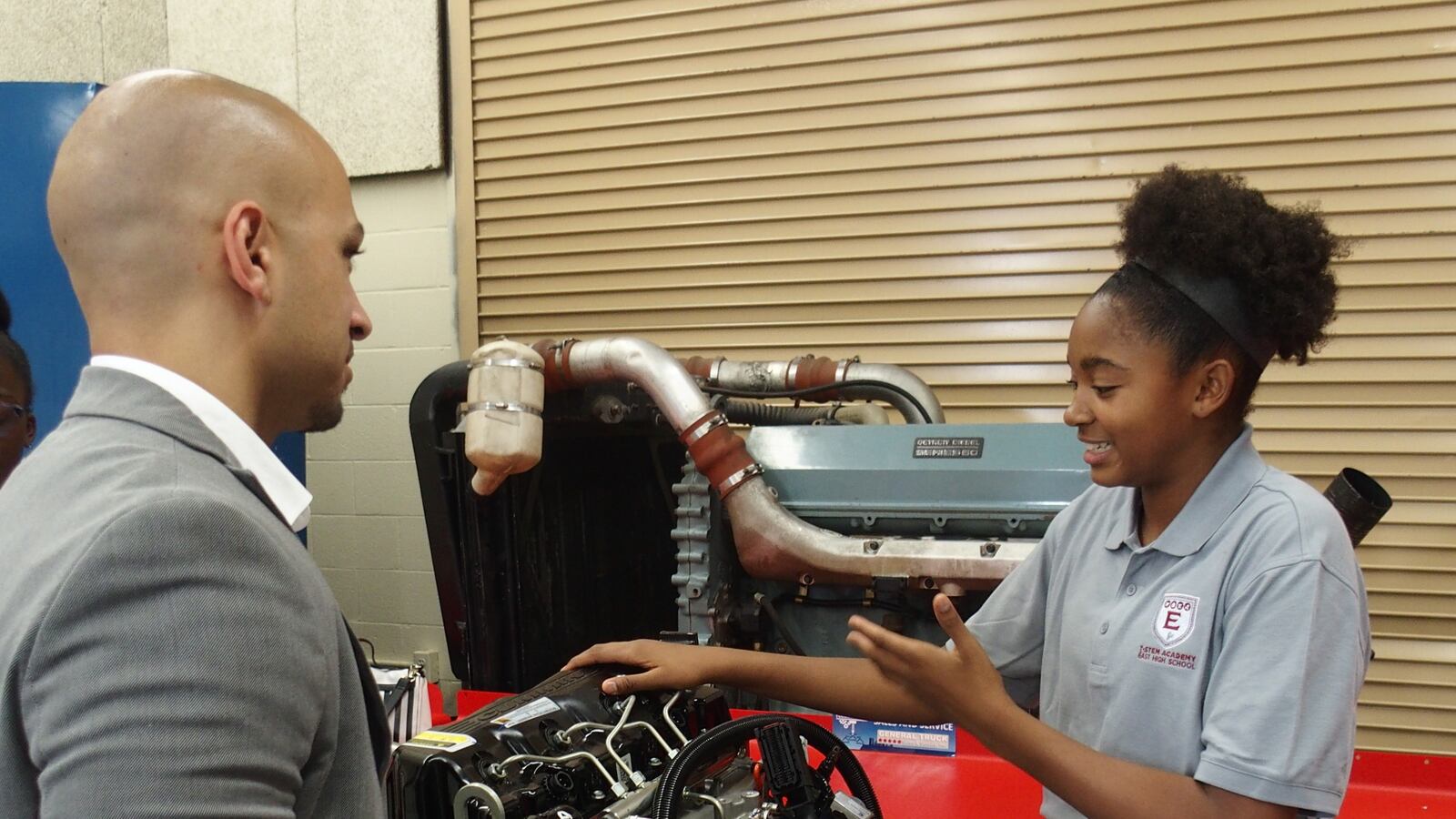

Shelby County Schools has heavily invested in the school since announcing the changes in 2016, including giving laptops to all students to take home, providing high-tech engines and trucks for students to practice on, and exploring a massive athletic field renovation. More than a dozen trucking and manufacturing companies have partnered with the school to provide job shadowing and training, including Indiana-based Cummins, a global manufacturer that chose East as the site of its first American technical education program. Students can earn job certificates, including a private pilot’s license through the FedEx Flight Academy simulator lab.

“I could tell everything was new. Who doesn’t want to go to a new school?” said Kia Bolton, a freshman whose mother graduated from East and decided to send her child there instead of a private school because of the new diesel program.

“I heard from my mom that East was falling,” said Bolton, who attended an optional program last year at Snowden School. “Memphis needs to change and this is just part of the change… This is the perfect place for this to happen.”

Superintendent Dorsey Hopson said transportation programs like the one at East will be a game-changer for students who live in poverty.

“I can think of no better opportunity than take kids who come here – even kids who don’t want to go to college – and learn a marketable skillset so they can take care of their families and change their circumstances in life, and break those generational cycles of poverty,” he told a group of business leaders this week who are partnering with East High.

Some feel left behind

In the first year after the school’s transition last year, students in the higher grades were allowed to stay and finish out high school there. But ninth graders were required to test into the specialty program, which enrolled 89 freshmen — 11 shy of the school’s goal. Other ninth graders were rezoned to schools in other neighborhoods.

Altogether, enrollment dropped to about 350 by February compared to around 500 the year before.

A local filmmaker has documented the stories of some neighborhood teens who feel excluded from the transformation taking place at the school.

Tray, a student featured in the documentary, “The Other Side of Broad,” said he was not allowed to register in August of last year. (Broad refers to the Memphis street that separates a redeveloped area and the rest of Binghampton, which has many families living in poverty.)

Tray, whose name was withheld in the documentary, said his motivation dissipated after he was not allowed to stay at the school.

“I didn’t want to go to school no more.” As a student from a poor family, Tray said, “you don’t know how much I went through to even get here. And for y’all to throw me out, I got to start all the way over.”

Filmmaker Lawrence Matthews, a graduate of Germantown High School, equated the transformation to “educational redlining,” a play off of the term used to describe racially discriminatory housing practices. He said Tray dropped out of school soon after he interviewed him for the film last winter. Memphis has the highest rate in the nation of young adults not in school or working.

And even though the recent changes to East’s admission requirements include more students, “there’s still… children who were affected by what happened,” he said.