Leading up to Betsy DeVos’s confirmation vote as earlier this year, CNN’s investigative team unearthed some provocative comments she had made in 2015.

“Many Republicans in the suburbs likes the idea of education choice as a concept, right up until it means that poor kids from the inner cities might invade their schools,” DeVos said in comments she described as “politically incorrect” at SXSWedu. “That’s when you’ll hear the sentiment, ‘Well, it’s not really a great idea to have poor minority kids come to our good suburban schools,’ though they’ll never actually say those words aloud.”

This sentiment wasn’t surprising to many in the education world, and now a new study suggests that the education secretary was right that suburban schools want to keep students from the city out, at least in Ohio. (The analysis was funded in part by the Walton Family Foundation, which is also a supporter of Chalkbeat.)

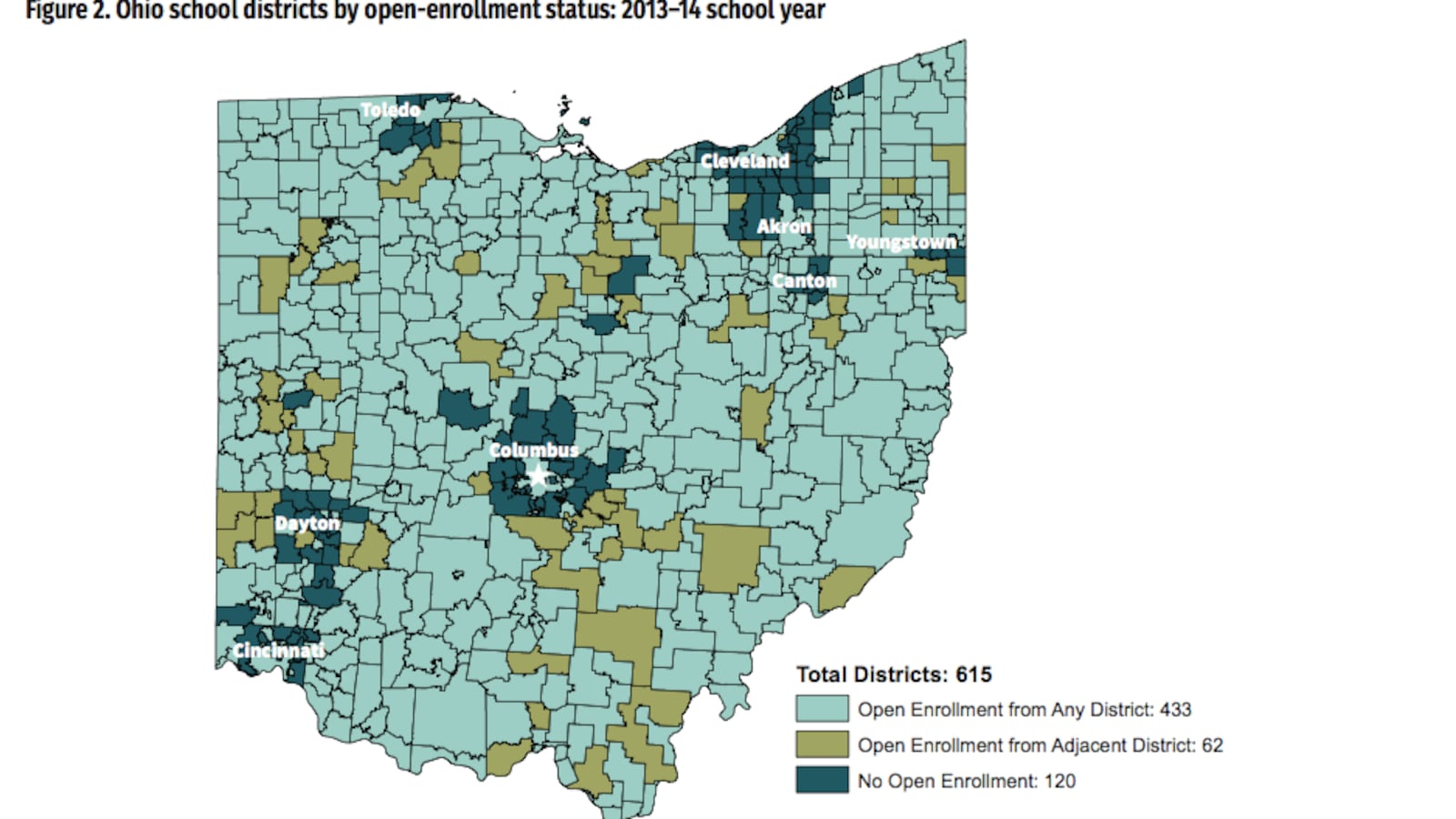

The report, released by the Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank, examines Ohio’s open enrollment system, which allows students to attend schools from outside their own district if the receiving district opts into the program. Most in the state did — perhaps because new students meant additional money — but some chose not to, as shown in the map above.

Notice a pattern? The districts that declined outside enrollment were predominantly ones surrounding major cities, like Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Dayton, all of which serve a large number of low-income students and students of color.

Suburbs might close their doors to city students simply because their schools are at capacity and accepting more students would place a strain on the system. But the study authors say that’s not the case: enrollment in the districts that don’t participate in the program actually declined on average.

On average, districts that refused open enrollment had higher achievement levels and lower poverty rates. While the largest eight cities in the state were composed of more than 70 percent students of color, the surrounding districts that declined transfers had fewer than 30 percent non-white students. This suggests that the suburbs’ decision not to take students from other districts may perpetuate school segregation.

“Whatever the reasons underlying district participation decisions, the decision of many suburban districts surrounding the [eight largest cities] to opt out of Ohio’s interdistrict-choice program removes some of the highest-quality educational options in the state from potential open enrollers,” write study authors Deven Carlson of the University of Oklahoma and Stéphane Lavertu of Ohio State University.

Perhaps in part because of the limited options for students in large cities, the students who do cross district lines were disproportionately white and economically advantaged.

The researchers also found some evidence that students, particularly black students, who attended school in other districts through open enrollment saw gains in achievement compared to similar students who chose not to participate. But these findings were inconclusive and the improvements were not necessarily caused by their choice of schools.

Students from high-poverty urban districts appeared to see the largest achievement gains from participating in open enrollment — precisely the students who often don’t have such an option.

“These findings create something of a paradox: those who are most likely to benefit from interdistrict choice are least likely to have access to the program,” the study concludes.