New York City’s public schools are suspending more students than they did a decade ago, and for longer periods of time, according to a report released today.

Data on student suspensions obtained by the Student Safety Coalition through Freedom of Information requests and analyzed by the New York Civil Liberties Union shows that the city’s public schools have doled out increasingly large numbers of suspensions each year since 2002. Black students are being suspended in disproportionate numbers, and a third of the suspensions have taken place during months when students spend weeks sitting for state exams.

The NYCLU’s report concludes that the spike in suspension rates over the years is connected to changes in the city’s discipline code, which now categorizes more infractions as being suspension-worthy than it did a decade ago. It also notes that the police presence in schools has increased since 2002, when former Chancellor Joel Klein started Operations Safe Schools.

Department of Education officials responded to the report, saying that in some cases principals can decide whether to respond to suspension-mandated offenses with lesser punishments.

“We are also working with our special education team to look at ways to address behavioral issues among special education students through stronger social and emotional mediation,” wrote DOE spokeswoman Marge Feinberg in an email.

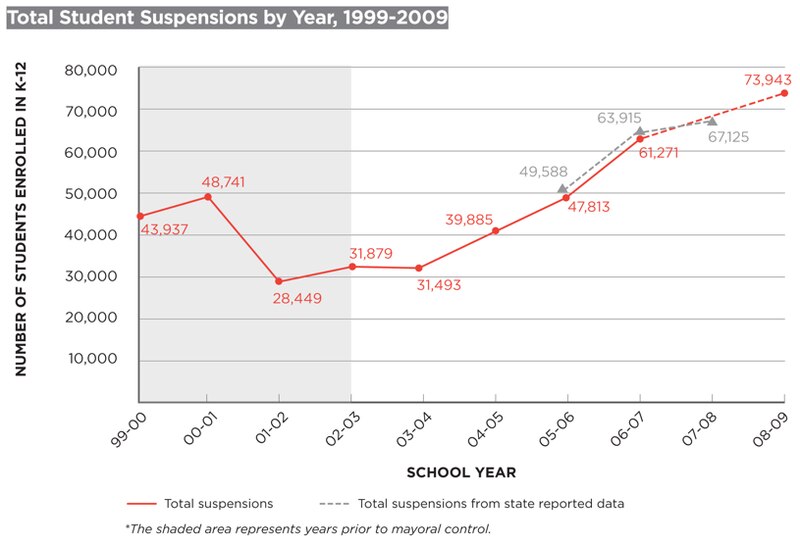

Analysis Finds Dramatic Spike in NYC Suspensions: Black Children and Students with Special Needs Most Affected FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 27, 2010 – The number of student suspensions in New York City public schools spiked dramatically over the past decade while the length of suspensions grew longer — a phenomenon disproportionally affecting black students and students with disabilities, according to a report released today by the New York Civil Liberties Union and the Student Safety Coalition that analyzes 10 years of previously undisclosed suspension data. “Education is a child’s right, not a reward for good behavior,” NYCLU Executive Director Donna Lieberman said. “Sadly, the growing reliance on suspensions in New York City schools all too often denies children — often the most vulnerable and in need of support — their right to an education. This harsh approach to discipline, combined with aggressive policing in schools, pushes kids from the classroom into the criminal justice system.” The report, Education Interrupted: The Growing Use of Suspensions in New York City’s Public Schools, analyzes 449,513 suspensions served by New York City students from 1999 to 2009. The NYCLU and Student Safety Coalition obtained the raw data for the report through a series of Freedom of Information law requests to the New York City Department of Education (DOE) in 2008 and 2009. Statisticians and academics at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University processed and analyzed the data for more than a year. According to the data, the number of suspensions served each school year nearly doubled over the decade – even though the student population has decreased over the same period. Among the report’s findings:

- One out of every 14 students was suspended in 2008-2009; in 1999-2000 it was one in 25. Last school year, students served more than 73,000 suspensions. In the 1999-2000 school year, students served 44,000 suspensions, even though the overall student population was much larger than today.

- Suspensions are becoming longer: More than 20 percent of suspensions lasted more than one week in 2008-2009, compared to 14 percent in 1999-2000. The average length of a long-termsuspensionis 5 weeks (25 school days).

- Students with disabilities are four times more likely to be suspended than students without disabilities.

- Black students, who compose 33 percent of the student body, served 53 percent of suspensions over the past 10 years. Black students with disabilities represent more than 50 percent of suspended students with disabilities.

- Black students served longer suspensions on average and were more likely to be suspended for subjective misconduct, like profanity and insubordination.

- Thirty percent of suspensions occur in March and May of each school year when students often are taking exams.

The report partially attributes the rise in suspensions to the DOE’s Discipline Code – the code of conduct for the city schools that catalogues infractions and the acceptable range of disciplinary responses for each one. From 1999 to 2010, the number of behaviors for which a student must be suspended grew by 200 percent. “If you increase the number of infractions that must draw a suspension, then more children are going to be suspended,” said NYCLU Public Policy Counsel Johanna Miller, the report’s primary author. “We encourage the DOE to continue recent steps to emphasize the need for non-punitive responses like peer mediation, guidance counseling, conflict resolution, community service and mentoring. These methods are proven to effectively address disciplinary issues while providing students valuable support and encouragement.” Research has repeatedly demonstrated that overuse of suspensions can worsen school climate and is linked to lower test scores. Studies also show that students who are suspended tend to be suspended repeatedly, until they either drop out or are pushed out of school. A study of secondary school students, published in the Journal of School Psychology, showed that students who were suspended were 26 percent more likely to be involved with the legal system than their peers. “The increasing and disproportionate use of suspensions in New York City schools negatively impact the school environment and drive down student achievement,” said Udi Ofer, NYCLU advocacy director and co-author of the report. “The Bloomberg administration must end its zero tolerance approach to school discipline and instead provide resources to schools to address the emotional and mental needs of children.” The overuse of suspensions combines with heavy-handed street policing tactics used in too many of the city’s schools to push students from classrooms into the criminal justice system. School safety officers, NYPD personnel assigned to the schools, have become increasingly involved in maintaining school discipline. Students, some as young as five, have been handcuffed, taken to jail, and ordered to appear in court for infractions such as writing on a desk or talking back. While school safety officers do not have the power to suspend students, they are often complaining witnesses atsuspension proceedings, and are usually involved when disciplinary infractions are treated as criminal offenses. The report offers the following recommendations to the DOE and state and city lawmakers:

- End the use of zero tolerance discipline. The DOE must ensure that suspensions are used only when truly necessary and that disciplinary responses complement rather than detract from a school’s educational mission. Other big-city school districts, like Los Angeles, Baltimore and Seattle, use discipline codes that are far less severe than New York City’s.

- Mandate positive alternatives tosuspensionwhen appropriate. In the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the second-largest school district in the country, a commitment to positive behavior interventions and supports reduced the number of suspensions by 15 percent in its first year. The DOE should follow LAUSD’s lead and ensure that all the city’s 1,600 public schools implement effective positive discipline, including restorative justice and positive behavior interventions and supports.

- Protect students’ constitutional rights insuspensionhearings. In order to protect students’ rights, the DOE must take steps to ensure that administrators are fully aware of and respect the procedural requirements for suspending a student.

- Increase transparency around discipline and school safety practices. Greater disclosure of data concerning discipline and school safety will help policymakers, educators, parents and advocates develop more effective policies – increasing the graduation rate and closing the achievement gap.

- Provide support services for students’ emotional and psychological needs. Schools must invest in guidance counselors, social workers and school aides who are trained in conflict resolution and restorative justice methods to handle disciplinary infractions. In addition, more schools should collaborate with medical, mental health and social service providers, as well as community based organizations, to address students’ non-academic developmental needs.

• Encourage meaningful public input in the discipline process. The DOE must show that it seriously considers the input it receives from parents and students during the annual Discipline Code revision process.