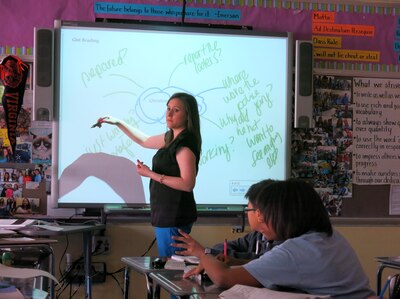

One bright afternoon this week, Catherine Miller’s 31 sixth-grade honors students sat inside a dimly lit classroom in the north Bronx and analyzed a 16th-century love poem. Its opening lines glowed on an interactive whiteboard at the front of the room: “Forget not yet the tried intent / Of such a truth as I have meant.”

The truth at The New School for Leadership and the Arts, or M.S. 244, the public middle school where Miller teaches sixth and seventh-grade reading and writing, is that the Common Core learning standards have transformed instruction over the past few years.

Miller now pushes her students to dig past the surface of challenging texts, like the poem by Sir Thomas Wyatt, and unearth their buried meanings. In the process, she says she’s made the standards her own. She selected the poem herself, for instance, and used it to supplement a publisher’s curriculum that is heavy on nonfiction.

The Common Core “is very much what you make it,” Miller said. “It can be your friend or foe.”

Chalkbeat spent Monday afternoon observing Miller’s reading class as part of our ongoing look at how the Common Core is reshaping instruction. Miller will join two other middle school teachers on a panel Thursday to talk about how the standards are playing out in their classrooms.

As when we’ve chronicled lessons before, we spoke with Miller after class and have included her thoughts in block quotes beneath highlights from the lesson.

12:58 p.m. As students opened their well-worn readers notebooks, Miller explained that the day’s lesson would explore the way writers use repetition to develop themes. In poetry, she added, repeated words are called a refrain.

A student went to the whiteboard and underlined the poem’s refrain, “Forget not yet,” then the class brainstormed other texts they had read with refrains. Next, Miller cut to the crux of the lesson: Why would Wyatt repeat those words?

“Remember, it’s not enough to tell me something repeats,” she told the class. “The real skill is explaining why there’s repetition — that’s what’s impressive.”

Miller said the purpose of the Common Core literacy standards is to prod students past a basic comprehension of a piece of writing to a more sophisticated study of the way authors assemble texts in meaningful ways. That shift has been apparent on the state exams, Miller said, which for the first time last year assessed students’ command of the new standards. “I remember on previous state tests, it was ‘Identify the metaphor,’” she said. “Now it’s, ‘How does that metaphor function and what’s the larger purpose of it within the piece?’” Last year, when citywide passing rates plunged on the new exams, more than half of Miller’s sixth-grade honors students saw their scores improve over the previous year and a third of her students earned 4’s, the highest possible score.

1:38 Miller turned the class’ attention to “Watcher,” a poem about Hurricane Katrina by the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, Natasha Trethewey.

Miller had chosen the first poem mainly for its use of the word “yet,” which was the subject of a recent grammar lesson. But she pulled in “Watcher” because it connected to their reading unit about natural disasters.

Before students tackled the text, Miller asked them to write and recite a few key vocabulary words from it. Then the class debated whether each word carried a positive, negative, or neutral connotation.

One girl argued that the word “looting” had a negative connotation because it suggested that people had taken advantage of chaos. In discussing the word “debris,” a boy referenced an article the class had read about space junk.

Besides previewing vocabulary in difficult texts, Miller also gives some historical context or has the class read related articles to gather background information. (In this case, they had already read about Hurricane Katrina.) The point is that before students can analyze texts, they have to make sense of them, Miller explained. “Without comprehension,” she said, “there will be no questions answered.”

2:09 Miller told the students to read the poem and underline instances of repetition. Then she asked them to reread it and jot down questions it provoked. She modeled this by writing a few questions on the board.

Next, the class drew charts in their notebooks with columns for the stanza number, textual evidence, and significance. The class had decided that the poem’s repetition centered on a character who watched New Orleans reeling after the hurricane.

Together, they found evidence of the repetition, then split off into pairs to document more. One boy and girl debated whether the focus of the final stanza was the character watching for remains or the speaker watching that character “bear the pain” of loss, as the boy put it.

The students knew to back up their arguments with examples from the poem, not their own experiences or opinions. As one student, Di’Anna Bonomolo, noted, “Ms. Miller doesn’t like first person.” Miller explained that many of her students had previously learned to preface statements about texts with statements like, “I think,” but that the standards called for evidence-based assertions. “You should be able to prove what you think,” she said, “so you don’t need to say, ‘I think.’”

Miller asked the students to fill in the significance column of their charts for homework: What was the point of all those moments of watching? As they do with most texts, the class would return to the poem the following day to dig for more meaning.

“It challenges you,” Ian Reyes, 11, said after class. “We’re trying to get deep inside the poem.”

Hear Miller and two other middle school teachers explain how they teach reading under the Common Core at a panel discussion co-hosted by Chalkbeat and the Bronx Library Center. The event is Thursday, May 8, at 6 p.m. at the Bronx Library Center.