Every fall, Scott Conti, principal of New Design High School in Lower Manhattan, faces the same challenge: absorbing a new cohort of students, many of whom didn’t pass the state’s math and reading exams in eighth grade.

Last year, of more than 100 incoming ninth-graders, only six who had taken the eighth-grade math test had passed. Only 15 had passed English.

Less than a mile away, there’s another school where the majority of ninth-graders passed the same exams — often with flying colors. And that school, New Explorations into Science, Technology and Math or NEST+m, is not alone: Dozens of city high schools have large concentrations of students who sailed through middle school.

The difference: New Design has little control over the students it admits, while NEST+m picks students based on test results and previous academic success.

“When the school opened, I don’t think we quite got how the admission policy would define us,” Conti said.

Indeed, high school admissions rules have placed New Design — and its students — in a system of staggering academic segregation. A small percentage of schools drain off the top students, leaving the majority of schools with very few students entering on grade-level.

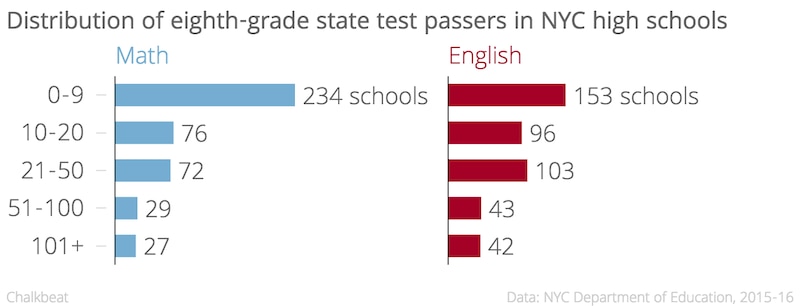

A Chalkbeat analysis found that over half the students who took and passed the eighth-grade state math exam in 2015 wound up clustered in less than 8 percent of city high schools. The same was true for those who passed the English exam.

Meanwhile, nearly 165 of the city’s roughly 440 high schools had five or fewer ninth-graders who took and passed the state math test in 2015. (Some students take algebra in eighth grade, so do not have to take the eighth-grade test.)

When it comes to English, the trend is similar, though less severe: There are 79 schools where five or fewer of last year’s ninth-graders had passed the eighth-grade test.

The city is engaged in a robust conversation about racial segregation in elementary school, which is driven largely by housing patterns. Yet high schools — which are open to students from every corner of the city — have maintained a parallel system of privilege by using academic “screens” instead of geography.

“Academic screens are a mechanism for sorting the students who have had educational privilege into places where they continue to get educational privilege,” said Megan Moskop, high school admissions coordinator at M.S. 324 in Washington Heights “And the students who don’t have that privilege continue not to have it.”

***

The city has long maintained some schools for very high achievers, including Stuyvesant High School, which started admitting students based on a test in the early 1900s. But between 2002 and 2009, there was a dramatic growth in the options available exclusively to high-scoring students.

In 2002, the year Mayor Michael Bloomberg took office embracing a platform of school choice, only 15.8 percent of school programs screened students for academic success, according to numbers provided by Sean Corcoran of NYU Steinhardt. By 2009, that share had increased to 28.4 percent. (Some schools house multiple programs with different admissions methods.)

The era marked an “under-the-radar explosion of screened schools,” said David Bloomfield, an education professor at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center.

At the same time the city whittled down the number of high schools designed to enroll students with different ability levels. In 2002, 55.4 percent of city high school programs were what’s called “educational option,” meaning they are set up to serve specific portions of high-achieving, low-achieving and average students. (In practice, few do.) By 2009, that share had dropped to 27.7 percent, according to Corcoran’s numbers.

The perils of screening have long been known. A team of researchers warned the city back in 1986 about some of the problems that remain in place today.

In 1986, then-New York City schools chancellor Nathan Quinones convened a group of researchers to examine high school admissions. The group, tasked with increasing access for students and maintaining school quality, warned explicitly against screened programs.

“As a general principle there should be no screened programs,” the report reads.

"I would hate to have my future determined by how I did in seventh grade."

Clara Hemphill

The report also argues against interviews, tests developed by schools, placement based on residence, and admissions credit for those who attend open houses. The goal was to avoid “invalid and/or biased admissions criteria.” Yet all of those admissions practices are commonplace in the high school admissions system today.

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has recognized these problems and started chipping away at them. The city is not interested in approving new screened programs, city officials said, and has reduced the number of seats in screened schools by 500 since 2015, a roughly 2.5 percent decrease in the percentage of screened seats. Officials also increased the number of educational option seats by 14 percent since 2015.

Additionally, many of de Blasio’s education initiatives have focused on strengthening high school curriculum and ensuring all students have access to advanced coursework.

“The work of fostering academic diversity goes hand-in-hand with our Equity and Excellence for All agenda to strengthen all our schools,” said education department spokesman Will Mantell.

Still, roughly a third of school programs today are either academically “screened” or require an audition. Floyd Hammack, a retired New York University researcher who worked on the 1986 report, said he sees echoes of the situation his team was trying to address.

For him, today’s high school landscape is like a bad flashback. “All this does, ultimately, is make people think that the system is a game that they’ve got to figure out how to play.”

***

The depth of academic screening in the city is eye-popping. Proficient students are concentrated in screened schools — which admit students based on tests, auditions, or prior academic performance — and at large comprehensive high schools, many of which set aside seats for high-achievers.

But there are fewer large high schools than in the past. Most of today’s schools are smaller, and may have few, if any, ninth-graders reading and performing math on grade-level.

City officials did not dispute Chalkbeat’s findings, but noted that about 18,000 eighth-graders took algebra in 2015 and since some of them skip the math exam, that muddies the statistics. (Those students are missing from the data as eighth-grade test takers, but it stands to reason they are also more likely to be enrolled in selective schools, meaning the general conclusions would likely hold.)

The city also said looking at the schools that enroll the most passers can be misleading, since those schools also enroll a disproportionate share of the city’s total students. Roughly a third of last year’s ninth-graders were in the schools Chalkbeat identified as home to more than half the city’s total English and math passers.

Still, the vast majority of students are not in those top schools.

The city’s intense academic stratification has consequences for student learning, explained Halley Potter, a researcher at the Century Foundation, a think tank focused on reducing inequality. Students in poor-performing schools often contend with ill-prepared teachers, lower expectations, and more behavioral issues, Potter said.

“When you sum up all of those studies, you see a really clear pattern that low-level tracks have harmful effects for students,” Potter said.

On the flip side, a number of studies, though not all, have indicated that mixing academic levels does not harm high-achievers. Potter pointed to a review of 15 studies conducted between 1972 and 2006 that showed that sorting students by ability level had virtually no effect, positive or negative, on average or high-ability students.

Alexander White, principal of Gotham Professional Arts Academy, had fewer than five incoming ninth-graders last year who passed their math or English exams the year before. He said he understands exactly why it’s so important to have a diverse mix of students. Imagine a class conversation about whether to keep the electoral college, White said. Having even a few high-performing students to guide the conversation could make all the difference, he said.

“Peer-to-peer education is like the secret ingredient in raising student achievement,” White said.

The stratification also means that many students are effectively shut out of top-tier schools. Just ask Gloria Carrasquillo, the guidance counselor at J.H.S. 151 Lou Gehrig, a school in the Bronx.

Each year, parents of eighth-grade students come into her office hoping to get their children into schools that send a high percentage of graduates to college. But Carrasquillo often has to break the news that there are few of those schools available to them, usually because their children don’t have the grades to qualify for screened schools.

“They don’t have the opportunity because they are blocked,” Carrasquillo said. “They are not admitted, so they cannot prove they can do better.”

"If we're just thinking about it plainly, screens are a function of exclusion for black and brown and low-income kids."

Matt Gonzales

Clara Hemphill, editor of the school-review website Insideschools, sees several problems with the current system.

Students in schools with mainly low-achieving peers may find there is no advanced coursework available to them, Hemphill said. Thirty-nine percent of the city’s high schools do not offer a standard college-prep curriculum in math and science, and more than half do not offer a single Advanced Placement course in math, according to a 2015 study by the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs.

The system also locks individual students into schools based on their seventh-grade grades and test scores, since that year is factored into high school admissions. That means there’s no second chance for a student to blossom academically in high school.

“I would hate to have my future determined by how I did in seventh grade,” Hemphill said.

***

While the city is trying to expand course offerings, including by allowing students on certain shared campuses to merge for Advanced Placement classes, other problems are more deeply entrenched.

At the top of the list: School screening has a long history of segregating students by race and income. Higher-income, Asian and white students are more likely to pass standardized exams than their low-income black and Hispanic peers.

While 25 percent of all city eighth-graders passed the state math exam in 2016, for instance, only 13.2 percent of black students and 15.9 percent of Hispanic students did. In English, 40.5 percent of all city eighth-graders passed the test, but only 29.2 percent of black students and 30.7 of Hispanic students passed.

The city’s most elite schools — the specialized high schools where admission is based on a single test — have come under fire for having few students of color. Only 4 percent of specialized school offers went to black students this year and just over 6 percent went to Hispanic students, though roughly 70 percent of the city’s student body is black and Hispanic.

But other screened schools reflect similar inequities, said Matt Gonzales, school diversity project director for New York Appleseed and an advocate for school integration. Any type of screen, whether it is a test, audition, or a look at previous academic history, will end up disadvantaging low-income students and students of color, he said.

Gonzales said high schools should be part of the citywide conversation about diversity, and that he hopes when the city unveils a large-scale plan to promote desegregation — which officials said they plan to do by June — it will include some measures geared toward integrating high schools. One of those measures, he said, could be further reducing the number of screened schools.

Screens “are designed to privilege and preference white and middle-class students,” Gonzales said. “If we’re just thinking about it plainly, screens are a function of exclusion for black and brown and low-income kids.”

Conti, the principal of New Design High School, knows firsthand that clustering higher- and lower-achieving students makes it harder for schools like his to succeed. He loves working with his students, but gets no extra support with the near-Herculean task of helping so many students entering the school below grade-level graduate on time.

Conti knows there are no easy answers. “It’s horribly complex,” he said. “It’s a knot right now that’s going to be very hard to untie.”