The Independent Budget Office released its third edition of the “Public Schools Indicators” report, a lengthy look at the makeup of the city’s school system.

This year’s report includes new information about the student population with the greatest needs, how often (and when) students leave the school system, where tens of thousands of students without permanent housing live, and how the city has used more than $100 million in Race to the Top funds.

The report comes out of a 2009 compromise with state lawmakers to extend mayoral control of the city schools in exchange for opening the Department of Education’s books to an outside fact-checker.

Here are five things we learned:

1. The federal funding floodgates opened to the city in the 2012-13 school year.

That’s when $107 million was earmarked to help implement Common Core learning standards in the first year they were aligned to new elementary and middle school English and math tests.

In 2010, New York state won a $700 million federal Race to the Top grant to improve evaluations, raise standards and upgrade its data system. About $300 million of that was set aside for New York City, but payment of the funds stalled, or had to be returned, because the city and the teachers union were unable to come to agreement on teacher evaluations and other key parts of the grant.

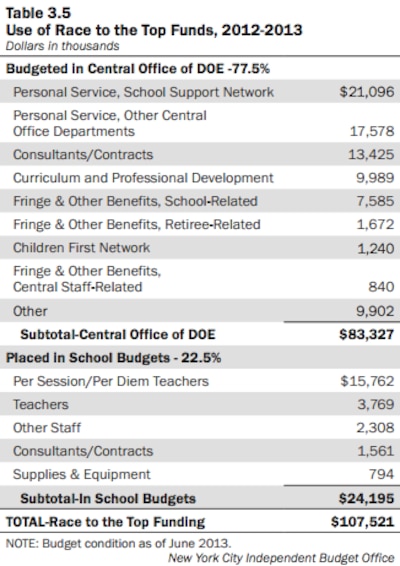

The city still received $62 million in grant money in 2011-2012, according to IBO Education Research Director Ray Domanico. But a bigger bulk came the next year as the state plowed forward in its implementation of the Common Core. More than three-quarters of the $107 million went to the Department of Education’s central offices, and $24 million went into school budgets. Almost all the money went toward manpower: an additional $21 million was spent on staff in school support networks, $17 million for staff in the central offices, and another $13 million for consultants.

When the money made it directly to schools, it was also spent on paying people: Nearly two-thirds of the $24 million allotted to schools was spent on teacher overtime and substitute teachers.

Ten million was also spent on curriculum and professional development, including a Common Core training program that Chalkbeat covered as it was rolling out in 2012.

2. Nearly one in every five English language learners also have a disability.

Students with disabilities and English language learners are often talked about as two separate groups that are historically underserved by the school system. But some of them fit into both categories, and their unique needs aren’t often a part of the policy conversation.

The percentage of English language learners with a disability is similar to the overall share of city students with a disability. But advocates said it was still alarming to see the numbers.

“These students are often among the most poorly served in the system,” said Kim Sweet, executive director of Advocates for Children. “With such significant numbers, this group really merits more attention from policy makers.”

Two-thirds of the city’s special education students are boys. Boys are also five times as likely to be identified as autistic as girls, slightly higher than the 4:1 ratio often cited in autism research.

3. Families are more likely to bolt from the school system when their children are young.

A look at students who started kindergarten in 2002 showed that just two-thirds were still in the system seven years later. Overall enrollment didn’t plummet, however, since new students were moving into the school system almost as often as those who left.

4. Students living in temporary housing increased 16 percent between 2010 and 2012.

The number of students living in homeless shelters is similar to the number in 2010, but a significantly larger share of students are “doubling up” as parents stay in a relative’s home. In 2010, 45 percent of students in temporary housing were “doubled up,” while 55 percent were in 2012.

5. Pre-kindergarten attendance lags.

Students in pre-K show up at a lower rate than any grade before high school. Pre-K attendance for the 2012-13 school year was 88.6 percent, more than two points below the 91.2 percent attendance figure for kindergarten students.

That’s a figure likely to be under more scrutiny soon, since Mayor Bill de Blasio has made pre-K expansion in the city his primary policy initiative through his first six months in office, promising that new programs will help narrow the achievement gap between poor and more affluent students.

Overall, student attendance was down slightly last year, from 89.8 to 89.6 percent, after several consecutive years of steady increases. The dip was likely related to the several weeks after Superstorm Sandy, when attendance rates in the most affected schools were low.

Other highlights:

— Principals have more leadership experience—but less teaching experience—than a decade ago. Principals during the 2012-13 school year had been in their positions for an average of six years, up from less than four years a decade ago. They had five fewer years of teaching experience, however—9.1 in 2012, down from 14 years in 2001.

— Teachers are sticking around. Prevailing wisdom is that urban school systems have a tough time hanging onto veteran teachers. But teachers actually have 1.5 additional years of experience, on average, than they did in 2005. (That period includes the recession, during which relatively few people looked to change careers, and an extended hiring freeze.) Last year, teachers had an average of 10.6 years experience.

— For a third year, we are reminded that co-locations don’t mean overcrowding. Co-locations are often portrayed as a source of the overcrowding problem in New York City schools. But single-school buildings are actually more over-capacity than ones in which schools share space.

The vast majority of the city’s 1,373 school buildings house just one school. Their average utilization rate, 105 percent, is significantly higher than the 88 percent utilization rates of 481 buildings with multiple schools.

— That doesn’t mean overcrowding is less of a problem. Since 2007, the share of city students who go to school in an overcrowded school has inched up, from 40 percent to 43 percent.

[documentcloud id=1211407-2014edindicatorsreport]

This post has been updated to reflect that 45 percent of students in 2010 were “doubled up,” not 48 percent.

Want the latest in New York City education news? Follow Chalkbeat on Facebook or @ChalkbeatNY on Twitter.