When a visitor walks into a second-grade classroom in Queens, she should see the same sort of work happening as in a classroom in Brooklyn, the Bronx, or any other borough, Chancellor Carmen Fariña said Tuesday while discussing her recent school-system overhaul.

“One of the things I was hoping the reorganization would do is that you don’t go into a school in one part of the city and a school in a different part of the city and see a very different focus,” she said. “You need to have more consistency. You need to have more kids all on the same page.”

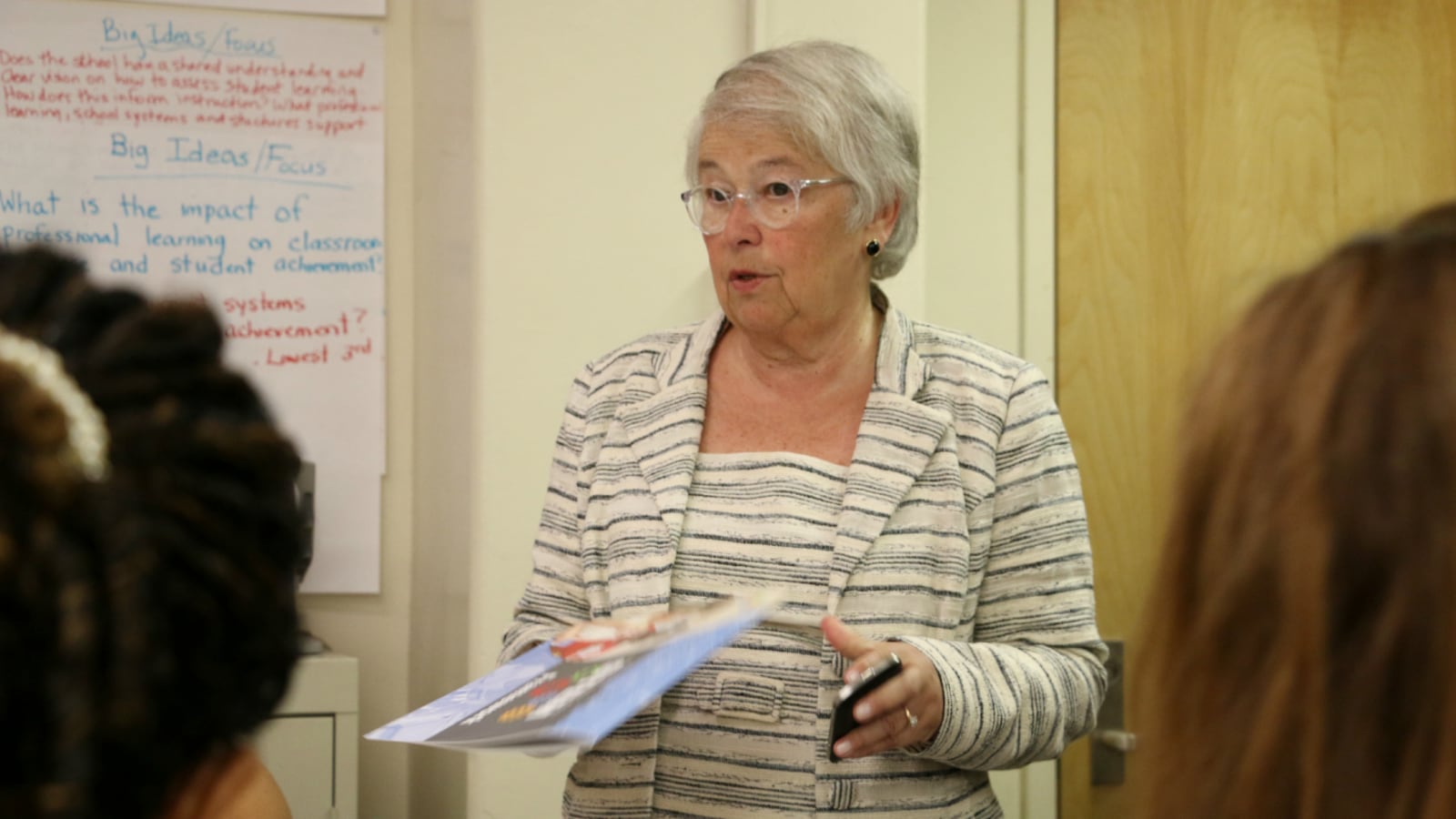

Fariña described her vision during a visit to one of seven new school-support centers, which the chancellor said will help create a more uniform school system by offering training and other assistance based on guidance from education department headquarters. The centers, which officially launched last week, are byproducts of Fariña’s school-system shakeup.

The new system, which put superintendents squarely in charge of principals and also established the help centers to assist principals, replaces a structure under the previous administration that gave principals considerable autonomy but left some feeling stranded with little support. Under the new centralized support system, all schools will receive the same high caliber of help but also be expected to reach the same high expectations, Fariña said.

That push for consistency makes sense, experts said, but it will be a heavy lift in a system of 1,600 diverse district schools.

“What she is trying to do is bring everybody up to a standard. The gap was widening when people were left on their own,” said Lily Woo, the longtime principal of Manhattan’s P.S. 130 who now runs a principal-training program at Teachers College. But, she added, “It’s much easier done in a system that’s much smaller.”

Under the old structure, principals chose from about 55 different multi-borough support teams, called “networks,” that helped schools manage everything from budgets and hiring to teacher training and curriculum. Now, principals will first turn for help to their superintendents, who will then refer them to one of the centers. Unlike the networks, principals do not choose their centers, they are assigned them based on location: Brooklyn and Queens both have two centers, while the other boroughs have one each.

The centers will act as a conduit for ideas from the chancellor’s office to flow into schools, Fariña said Tuesday.

For instance, the deputy directors at each support center in charge of instruction, special education, and services for English learners have been meeting with the education department officials who lead those divisions. The deputies will then oversee workshops at their centers on topics like reading instruction or special-education methods, which representatives from each school will attend, then train their colleagues on.

“There will always be a connection from the deputies to Tweed, so there’s one message only,” Fariña said, using the name of the education department headquarters. “This is not, ‘You decide what you want to do because you’re here, versus over here.’”

Under this model, superintendents are tasked with making sure principals get the help they need from the centers, and also that they are running their schools according to the city’s guidelines. With clearer instructions from the department about what should happen inside classrooms and during teacher trainings, superintendents will have an easier time supervising schools, said Kim Nauer, education research director at the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs.

“The giant philosophical change is that the principals now have bosses: the superintendents,” she said. “If you’re going to do that, you have to have some level of consistency in terms of what the superintendents are looking for in classrooms, and in terms of the supports they’re offering.”

However, the urge to standardize practices at schools comes with risks.

Former Chancellor Joel Klein — the same schools chief who created the network system that freed principals from much department oversight — ordered most schools to adopt standard reading and math programs. As Klein’s deputy chancellor charged with rolling out that initiative, Fariña was accused by some teachers of micromanaging what happened inside their classrooms. Klein eventually backed off that approach, and schools were later allowed to choose their own curriculums.

Nauer said that most schools could use guidance in certain challenging areas, such as adapting lessons for students with special needs, so it would make sense for the department to suggest research-backed practices. But it would be impractical to try to make schools serving different student populations adopt identical teaching methods, she said.

“This is a giant school system with all types of very different kids,” she said, “so I doubt you could take a single model of anything and make it work across the board.”

Fariña said Tuesday that she has no plans to do that.

She doesn’t want “robotic teaching or robotic principals,” but rather ones who make instructional decisions based on their students’ particular needs. And low-performing schools will receive personalized support, she has said.

Still, she recalled how as an elementary school principal she wanted sixth-grade teachers across the city to expect a certain level of preparedness from her graduates. With more uniformity across the school system, teachers today could have similar expectations of their new students no matter what schools they came from, she said.

“That’s really what I want to see,” she said. “I want to see more congruence and consistency.”