This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

It’s PTA night at George W. Nebinger School, and a dozen parents face a full agenda: the fall festival needs more face painters. The pie sale raised $1,700. The book fair needs volunteers, especially during the day.

Then, about half an hour into the meeting, parent Michele Ditto rises to report on the District’s new strategic planning process – an effort that could change everything at Nebinger, or nothing.

“We don’t know what the outcome is going to be,” said Ditto, standing by the door of Nebinger’s colorful new library. “But they showed us a slide of what could be” — closures, expansions, replications, consolidations, even redrawn catchment boundaries.

“Overcrowding, enrollment, everybody has different situations,” Ditto explained.

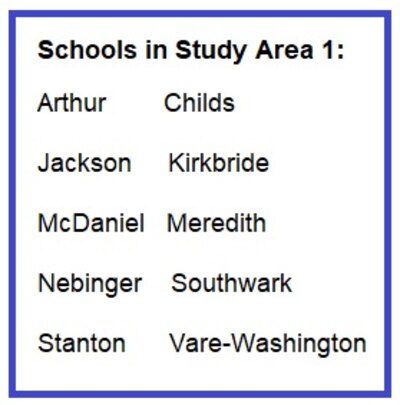

The night before, Ditto was part of a Nebinger delegation that met with District officials to discuss the Comprehensive School Planning Review (CSPR), a multi-year project designed to better align District policy with changing city demographics. Over 40 people from 10 South Philadelphia schools gathered to learn about the coming process. Parents, teachers, and District staff spent two hours talking about how to create a comprehensive education plan for the entire community.

The whole thing is just getting started, Ditto explained. But even the initial discussion helped the Nebinger team identify an early priority.

“Our concern was, are we going to lose choice? A lot of us are from out of catchment,” said Ditto. “That’s where we are now.”

The words “school of choice” mean a lot at Nebinger. Six years ago, the school was nearly half-empty and slated for closure. Now it’s bursting at the seams. Halls are clean, classrooms cheerful. Students have enrolled from across the street and across the city. Two-thirds are from out of catchment.

“We’re using every inch possible,” laughed Principal Natalie Catin-St. Louis.

Among the students are Dwayne Peel’s daughters, who come here each day from West Oak Lane – a 30-mile round trip. He’d been unhappy with his neighborhood school, and a friend from South Philadelphia recommended Nebinger. Peel visited and liked it immediately: the atmosphere, the principal, the offerings. Now he’s a committed booster, active on both the PTA and the School Advisory Council (SAC).

“I probably come farther to be here than anybody,” Peel said with pride.

Peel is the kind of parent the CSPR aims to help. Children like his shouldn’t have to travel 15 miles to find quality, District officials say. They should have a great schools right in their neighborhood, with a clear feeder pattern carrying them along.

But Peel’s is also the kind of family that CSPR could disrupt. If Nebinger’s feeder patterns are tweaked to attract more neighborhood students, out-of-catchment families like Peel’s could be nudged out. If Nebinger is reconfigured as a K-5, a families like Peel’s that include elementary and middle schoolers would have to split the kids up.

District officials know these kinds of complications lurk everywhere, and they promise that the CSPR process will tread carefully. But they also say that they’re committed to planning for entire neighborhoods, not just individual schools, and they know that could put them in conflict with parents who’ll fight to protect what they’ve already got.

Standing outside the library at Nebinger, Peel says that no matter what CSPR may propose, his goal will stay the same: to keep his kids where he wants them.

“Let me put it this way,” he said. “Come hell or high water, my children are going to get the education they deserve.”

Considering schools as a group

It’s highly unlikely that Peel’s children will lose their spots in Nebinger. Changes to catchments and feeder patterns take years to implement, and District officials have said they expect to “grandfather” in affected students in order to minimize disruption.

But the West Oak Lane father’s commitment to his South Philly choice reflects a pattern seen nationwide: few families oppose the concept of system-wide improvements. But whenever specific changes are proposed, they’ll fight hard to protect whatever advantages they already enjoy.

A case in point: Meredith Elementary in Queen Village, which like Nebinger is part of the South Philadelphia CSPR study area. Properties in the coveted Meredith catchment sell at a premium, and changing boundaries could hit homeowners square in the wallet. That’s why one Philadelphia real estate developer greeted CSPR with an email blast: “This could be the mother of all battles.”

The CSPR plan seeks to avoid such parochial paralysis by organizing its process around groups of schools, bringing together school delegations to collectively help develop “comprehensive” plans for entire neighborhoods.

Vanessa Benton, the newly hired planning specialist in charge of the District’s CSPR team, said she’s prepared for what could be a wide-ranging, emotionally charged public debate.

“People are passionate about educating their children, and they should be. I was passionate about raising mine,” said Benton. “Some people are going to love it, some people are going to hate it, and they have every right to express that. But it didn’t deter me from taking the job, and it’s not deterring me from doing the right thing.”

District officials have some basic priorities for South Philadelphia and this year’s two other “study areas” (parts of North and West Philadelphia). They want clearly defined K-12 feeder patterns, equitable distribution of programs, and full access to pre-K.

To reach those goals, officials say, all options are on the table. Schools may be closed, expanded, or reconfigured; whatever the data shows can help the entire community. “We are thinking of solving for the challenges of the entire study area – not [just] one school,” said Benton.

In South Philadelphia, that means the assembled school communities must work with the CSPR team to craft a proposal that deals simultaneously with issues at overcrowded, high-performing schools like Jackson and Meredith, and less popular, struggling schools such as Childs and Key.

They must grapple with the needs of newcomers and longtime residents, working class and professional families, college-bound and workforce-bound students. They must account for the needs of every race, gender identity, language and life condition. Pregnant students, homeless students, traumatized students, high-achieving students – the South Philadelphia study area plan must accommodate them all.

Joan Fanwick, a third-year special education teacher at Nebinger, said the opportunity is long overdue. “What I really like about the process is that it’s bringing the schools together,” she said.

The South Philadelphia study area is varied and representative, she said, including prosperous professionals, working- and middle-class families, public housing residents and immigrants. “We have a [diverse] slice of socioeconomics,” she said.

But South Philadelphia has a challenge too, Fanwick said: catchment boundaries have remained unchanged for so long that some residents feel “entitled” to their spots in the choicest schools. CSPR could force the Board of Education to consider some very unpopular decisions, she said.

“Catchments are something that has to be rethought,” Fanwick said. “It’s going to make a lot of parents unhappy, but we have to think about all of our kids.”

Nonetheless, Fanwick is optimistic, and so is Catin-St. Louis, the Nebinger principal. Now in her third year, she welcomes the chance to address South Philadelphia’s needs in a comprehensive way.

“We’re looking forward to the opportunity to work through obstacles, not isolated, but with neighbors,” she said. “Because we do have great ideas we can share.”

The demographic data that the District promises to make available may prove helpful, Catin-St. Louis said. “It depends what the data is, and where it comes from,” she added with a smile.

But the wisdom of the community will be invaluable, she said. Nebinger’s parents and staff are ready to work, she said, and they’ll deserve to see their contributions taken seriously.

“A commitment we’d want is that the plan we develop is represented in the final product,” Catin St.-Louis said. “Time and energy, you can’t get back.”

A narrow window, a closed door process

Catin-St. Louis has dealt with her share of thorny neighborhood issues; spillover from overcrowded Meredith, for example, cost some Nebinger families their kindergarten spots. She and other principals have some ideas about how to improve the situation, and CSPR could be their opportunity.

But with the District aiming to finalize its neighborhood proposals by early April, Catin-St. Louis will have just a few months to bring her ideas into the CSPR conversation.

And while District officials promise a “transparent” process, most of this winter’s discussions will take place behind closed doors.

Each study area “planning committee” – the group that comprises delegations from all the individual schools – will meet a total of seven times between November and March. These planning meetings will be closed to the public. School delegations will be free to discuss the proceedings with their school communities, Benton said, but the District will be “very careful” about what it releases.

“It’s not that we don’t want to share the data … but it’s complicated,” Benton said. “We don’t want to put something out that might trigger a reaction, when it’s incomplete … we don’t want to jeopardize success by sharing data prematurely.”

Benton said that if participants like Catin-St. Louis bring proposals, the CSPR team will test them to see how they might affect the entire study area.

“They bring that plan, we look at the data,” said Benton. “We can test that hypothesis and run it through the models.”

But specific proposals will also come from CSPR’s “advisory team” of senior District educators and department heads – a group of a few dozen people that will feed data and options to the planning committees and review their responses, “volleying” ideas and information back and forth throughout the process, Benton said

Each of this year’s study areas will also have two public meetings; one in January, as the process gets going, and a second in April.

By that month, Benton expects her team to have drafted neighborhood proposals for consideration by the Board of Education. Those plans will be publicly unveiled in April, and the month of May will be set aside for public comment and debate.

The Board’s final vote on all three study area plans is expected in June.

Benton hopes the combination of useful data and an inclusive process will result in policies popular enough to withstand public scrutiny. But she said she’s ready for what could be a contentious spring.

“I accepted this [job] with the understanding that it was going to be a challenging role,” she said.

Cautious optimism, quiet concerns

In South Philadelphia, many parents are cautiously optimistic about CSPR. They see the need for planning and welcome the opportunity to contribute, even if the process doesn’t promise immediate results.

“I am happy to see that the District is finally working toward a long-term plan to address overcrowding in our South Philly schools,” said Sarah Kloss, a parent at Jackson Elementary who’ll be part of the planning committee. “The study won’t address some of our short-term issues, like the annual scramble to see if next year will be the year we need that additional classroom … but it could be a step in the right direction.”

But skepticism is out there, too. “It’s going to be a nightmare,” said another Jackson parent, Aaron Edelman.

Edelman said that it’s clear that a better plan is needed for South Philadelphia and Jackson, a K-8 near the Italian Market. “When I moved in here, it was all Italian grandmothers,” he said. Now, he said, it’s full of young families who are likely to stay.

But Edelman has little confidence in the District’s ability to make good on promises, or the Board of Education’s ability to challenge the status quo. “Politically, it’s not going to happen,” he said. “Too little, too late.”

Benton knows there’s only one way for her and her team to defeat such concerns: by doing “what we say we’re going to do.”

At Nebinger, members of the School Advisory Council (SAC) greeted news of the CSPR with cautious optimism, and a few quiet concerns.

One reason for hope: the recent toxin-cleanup effort. After years of neglect, SAC members said, Nebinger has developed a productive working relationship with District facilities staff. Problems are getting reported and fixed. Fanwick said she’s eager to carry lessons from that partnership into the CSPR process.

“We finally feel heard,” Fanwick said. “It’s reassuring and empowering.”

But the Nebinger SAC also had questions: how candid will the committee meetings be? What data will be available and when? Once final proposals are drafted, will Nebinger and other schools get any more chances to weigh in?

Many of the answers remain unknown. Benton said that much of next year’s process is still being developed. Study area committees like South Philadelphia’s will continue to play a role, but exactly how she can’t yet say.

“We are looking at building the administrative procedures,” she said. “We’ll figure out how that works in the second year.”

That leaves parents and staff at Nebinger focused on the positive. As November’s PTA meeting came to a close, Michelle Ditto said she’s excited by the possibilities CSPR offers, like replicating popular magnet school programs. She didn’t want to dwell on the pitfalls; she knows there’s a long way to go. “It’s so early!” said Ditto with a smile, as children streamed past her into the library. “I’m just excited about the process.”