This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Last Monday morning, Adrian Jackell was ecstatic. It was his first day back in his early childhood center in more than three months. The plastic gowns and face shields he saw on his teachers may have been new, but the wide smile on his 3-year-old face was the same as ever.

“He loves it,” Rob Jackell said of his son. “He’s been excited to come back. I think he’s going to be happy to play with other kids, since it’s been so tough for him.”

Adrian’s parents, Rob and Mara, brought the boy to St. Mary’s Nursery School, a fixture in University City for decades, as soon as its doors opened at 9 a.m. He was greeted warmly by his teachers and couldn’t wait to start playing with his friends. Soon he would be happily sitting on a classroom floor, poring over a book with a classmate, as if nothing had changed since last spring.

But all was not normal.

As parents arrived, they found the St. Mary’s entrance blocked by a desk with a clear plastic barrier protecting teachers from children. Center director Traci Childress and her staff greeted families while looking like something out of a science fiction movie, with clear plastic face shields and colored plastic gowns covering their clothes. Oversized ID tags showed pictures of the smiling faces hidden by their masks – so the children will be less confused, Childress said.

As the morning birds sang amid dappled sunshine, the Jackells stood six feet behind their son, watching him approach the desk like a tiny traveler checking in at the airport. There, a staffer scanned his temperature and watched him carefully sanitize his hands. Then, with words of praise and smiling eyes, they escorted the boy past the barrier and into St. Mary’s. He turned for a last happy wave at his family and then disappeared into the building.

It was the center’s first day open since it abruptly closed on March 16 – a joyful occasion, but also one filled with uncertainty and fear for the future of Philadelphia’s child care sector.

‘Underfunded and under-enrolled’

“It was a broken model before, an underfunded model before COVID,” Childress said. “Now it’s underfunded and under-enrolled.”

Experts, parents, and advocates agree: The U.S. economy cannot function without reliable child care. Families like the Jackells depend utterly on places like St. Mary’s.

Mara and Rob Jackell. (Photo: Bill Hangley)

“We need to be able to work. So they need to be open,” said Rob Jackell after his son was safely inside. “I don’t know what we’re going to do if they close again. Especially if they’re open for only a few weeks and they close again.”

The same is true for thousands of families across the region as the sprawling and diverse child care sector struggles to adjust to an unprecedented challenge. As the states and federal government during the coronavirus shutdown have been crafting various rescue plans designed to reopen businesses and help furloughed workers make ends meet, child care has received some help. But, advocates and providers say, it’s not nearly enough.

For most of the time between March and last week, Childress and her staff worked tirelessly to prepare for when they could resume business. They made sure that they followed every federal Centers for Disease Control & Prevention guideline, took every possible precaution, and could handle any eventuality. Childress became an expert in best practices and made presentations to her colleagues in the field.

She also had to reduce her staff, stock up on personal protective equipment (PPE), and keep in touch with families who, she knew, may or may not come back when the center reopened.

Even if all the families do want to come back, it’s not that simple. For although St. Mary’s had to spend extra money to pay for PPE and cleaning, social-distancing guidelines say that it cannot enroll the same number of students unless it rents another room. Every day is a new challenge, as changing directives translate into new costs and new questions. Among the center’s many changes: They gave up five rented parking spots in order to save $10,000, which will help balance the ever-growing PPE budget.

“Last week, the governor said children needed to wear masks … so we went ahead and ordered children’s masks. But that was quite expensive,” said Childress. “That came out Friday, and we’re opening today, and the masks aren’t here yet. And that was two and a half thousand dollars.”

Operating on a shoestring

For child care centers like St. Mary’s, this is just one more expense, leading to a grim bottom line: COVID-related costs and demands are going up, while revenues are going down.

“Think about having half the kids and twice the cost for each kid,” Childress said.

Traci Childress, director of St. Mary’s Nursery School. (Photo: Bill Hangley)

In the best of times, the child care sector operates on a shoestring, especially in a city like Philadelphia, where so many families are low-income. It’s a tight margin business, marked by the paradox: The workers are generally not well-paid, while the costs, especially for private-pay families, are high.

In the city, most of the students who are eligible for publicly subsidized programs such as Head Start, Child Care Works, and PHLpreK attend privately run centers like St. Mary’s, which receive a subsidy for each child. And most providers in Philadelphia serve a combination of children – some subsidized and some who are “private pay” and assume the full cost. In addition, the subsidized families contribute a co-pay that varies based on their income.

With the centers now resuming business after more than three months, many child care providers are afraid that policymakers will take it as a sign that they are in good shape and that the state rescue plan for the sector did its job. But that is not the case.

“Just because we can reopen doesn’t mean everything is fine,” said Jackie Groetsch, public policy field organizer for First Up, an early childhood advocacy group that until recently was called the Delaware Valley Association for the Education of Young Children (DVAEYC). “That’s important for elected officials to know.”

Programs like St. Mary’s, she said, “are taking it extremely slowly and weighing decisions in a thoughtful and intentional way,” she said. “Do they have the ability to open safely and maintain all the CDC guidelines?”

Through the federal CARES Act, Pennsylvania received $106 million in federal Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG) funds. The state distributed $51 million of that in June, and the second portion of this funding, $53 million, will be distributed in July.

In addition, Gov. Wolf and the General Assembly chose to devote $125 million in CARES Act funding designated for education in general to early learning programs. Of this amount, Groetsch said, $116 million will go to child care, $7 million to Pre-K Counts, and $2 million for the Head Start Supplemental Assistance Program.

The child care funding will be allocated based on recommendations from a study being conducted by Pennsylvania State University on the impact of the pandemic on the sector, she said, and the Pre-K Counts and Head Start funds will be issued separately to current grantees on a per-slot basis.

To help child care and early childhood centers weather the pandemic, the William Penn Foundation and Vanguard set up a $7 million emergency fund, which is being administered through the Reinvestment Fund.

City-wide survey on child care

As part of this, the Reinvestment Fund, Philadelphia’s Office of Children and Families, the Public Health Management Corp., and United Way are conducting a city-wide survey to understand child care needs as people head back to work and school.

The survey will be open on the Reinvestment Fund website for two weeks and is available in eight languages.

“The CARES Act funding is a positive initial investment, but additional significant relief is still needed to support the child care industry so programs can keep their doors open to meet the needs of working families,” said Groetsch. Some centers also received Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans.

But already, Groetsch said, 65 centers across the state have said they will not reopen.

St. Mary’s teacher Genevieve Abaara shows off her ID tag. (Photo: Bill Hangley)

There is movement on the federal level for considerably more support. Sen. Patty Murray of Washington state and Rep. Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut, both Democrats, have introduced the Child Care is Essential Act (S. 3874 and H.R. 7027), which would create a $50 billion Child Care Stabilization Fund. Murray is the ranking member and DeLauro is the chair of the committees that oversee the sector in each house of Congress.

Whether this or legislation like it will pass, given the political atmosphere in the nation’s capital, is another question.

“This is an industry that had tight margins to begin with,” said Nelida Sepulveda, early childhood policy director for Public Citizens for Children & Youth. “Any bump in the road may push them over the edge.” Without further assistance, she said, “some of our more savvy, more sophisticated providers don’t see the model working past six months.”

If schools in the fall do not resume on a full-time, in-person schedule, as now seems likely, the pressure for reliable child care only grows, she said.

“Parents need to go to work,” she said. “Is the child care sector able to absorb kids outside the normal age group they work with? Who will take care of these children?”

Many centers haven’t even started thinking about that, she said. “Folks are just struggling with reopening, trying to figure out how to be viable as a business, provide quality care, and ensure safe and healthy conditions to the degree they can control it.”

Childress and other providers said the problems were daunting and the questions endless.

“They said you don’t have to reduce the size of your classes, but if you follow all the guidelines on the mats for naps, where you had 20 kids, you can’t get in more than 10 or 11” in the same space, she said. But that number of children “puts me at less income.”

Before the pandemic, 138 families sent children to St. Mary’s in three programs: toddlers, pre-K, and afterschool, ranging in age from 18 months to 12 years. The toddlers and preschoolers would be separated during the day, then combined when the afterschool contingent came in.

But because it is so hard to socially distance young children, the CDC guidelines recommend not mixing the age groups. To continue with the three programs, she will have to find another room or severely cut down on the number of children served.

Then there is the issue of whether parents want to come back. Childress said that 31 of her children said they were coming back in July; normally, she said, she would have 70 children for the summer program. As of the beginning of July, she had 41 children enrolled for the fall, compared to 100 in normal times.

“My hope for September is that I can find additional space for afterschool programming, and we can increase our enrollment with those kids,” she said.

The state continued to pay the child care centers their subsidies through the pandemic. But the centers still lost income from the parent co-pays and the private-pay clients. Some St. Mary’s private-pay families sent in a check for April even though the center was closed, but it and other centers hope to eventually refund that money. And some centers got forgivable Paycheck Protection Program loans to help with payroll.

But to stay solvent, Childress still had to reduce her staff from 30 to 17.

Mounting costs

And other costs continue to mount. The plastic gowns cost $4 each, and they are recommended by the CDC for one use while changing diapers. That means that one staffer could go through three or four a day. The alternative is to invest in a washer-dryer, but that also would involve the installation of a water line.

Through the CARES Act, St. Mary’s received $10,000, based on its March enrollment of roughly 100 kids.

“When we were at 30 staff members, that didn’t even cover our payroll,” she said. “It’s helpful, but it’s not enough. We’re opening at a deficit, and we’ll run at a deficit until we can increase the number of children we serve. What we need is money to finance high-quality programming and make sure we get through this.”

Other providers say the same thing.

Between March 13 and June 5, when they reopened, “we lost $330,000,” said Susan Kavchok, CEO of Childspace, a center with locations in Mount Airy and Germantown. The first round of PPP loans covered $269,000 of that, and Kavchok tried to fundraise for the rest. And some families also paid the April tuition even though the center was closed. “A lot of our parents were very understanding,” she said.

Childspace, which first opened in 1988, didn’t lay off any teachers and asked them to do virtual teaching from home, but as a center that serves a combination of private pay and subsidized clients, it was tough to make ends meet. In some ways, centers in which most of the students are subsidized were better able to survive, because the state continued to pay the subsidies. Some centers also laid off more staff members so they could collect unemployment benefits, so they didn’t have to use the state money to meet payroll.

And some centers feel they have to hire additional teachers to make sure they can maintain staffing ratios and their high state ratings, in case of illness. Then there are the additional cleaning costs, for materials and staff. Childspace spent $2,500 on supplies and $1,500 on a cleaning service.

“If we get sick, we’re not cutting classrooms down,” Kavchok said. “We hired three additional staff to do that.” The CDC recommends this, and parents expect it, “but on a financial level, how viable can that be beyond July and August?”

She doesn’t want to think about what will happen in the fall if students are not in school full time.

“What I’m finding unbelievable is that there is no discussion of what families are going to do if these kids are not in school,” she said. “I’ve heard this, that school is not day care, but the fact is that many parents rely on school so they can work. I don’t know how the economy will reopen if we can’t get these people back to work.”

Smaller, home-based centers are also uncertain about the future.

Kimrenee Patterson runs a center out of her West Oak Lane home that, at its peak, accommodated 10 children. The younger ones were full time and a contingent of older siblings came after school. The group includes some of her nieces and nephews. She was able to stay open for much of the time since March because several of her parents are essential workers with a few children.

Patterson worked hard to attain high-quality status from the state’s Keystone Stars program, earning the maximum four stars. Keeping that status during the pandemic has been daunting.

“It’s a lot more work,” she said. Student-staff interactions follow a whole different rule book. “It’s not a typical day with a lot of instruction. And it’s very different compared to our day where we do a lot of affection, can’t do any of that right now.”

Then there are the safety guidelines. “The staff is mandated to keep masks on as much as possible,” she said, adding that in the heat, that can be “overwhelming” but the rules are rigid about it when it comes to diapering, naptime, “and anything where we have close proximity. Handwashing is constant, wipe-down is constant, there is twice as much sanitizing of toys. One thing I stress to parents and staff, I want to take the ‘f’ out of fear. We don’t want to put fear in the children, but we want to make sure we put healthy practices in place.”

Patterson, who opened her business in November 2017, has consulted a nutritionist and has put more fruits and vegetables in the children’s diets to boost their immune systems. She asks parents to be careful where they go so they don’t expose their children, and therefore the staff, to additional risk. She even lets parents drop off the children when they go on supermarket runs to minimize their contact with others. Toys are sanitized after the children use them, and sheets are washed after every nap.

“The most important thing during this time is trust,” she said. “Our families have been with us since we opened. We don’t have high turnover, so it’s easier to talk about the realities of what we’re all going through with parents.”

Financially, due to the pandemic, she said, “I’ve lost 25% of my income.” But she has been scrimping and saving to make it work. Like the others, she has no idea what will happen if students only attend school occasionally in the fall and are expected to spend a lot of time doing schoolwork virtually.

“The parents want to know will [the older children] be able to come here with their computers full time, and if we can help them with their assignments,” Patterson said. “I told them I didn’t know, I would find out as we move along.”

Parental decision-making

Parents are doing their best to make the right choices in an ever-shifting landscape. Laura Nikoo and her husband, both administrators at the University of Pennsylvania, are faithful Childspace parents. Of course, they want to do what is best for their family and their children, but they also worry about the future of the industry.

“I think that this issue of child care sits at the nexus of all of the intersectional competing issues during COVID,” Nikoo said. She and her husband were both able to work from home, and they appreciated spending more time with their three children, who are 1, 3, and 6 years old.

But even if work habits change permanently and parents spend more time at home – and despite some concerns about safety – Nikoo wanted her children to return to Childspace.

Laura Nikoo and children Anna (left) and Simon on their first day back at Childspace. (Photo: Dale Mezzacappa)

“We knew we wanted to support the health and vibrancy of a community that has supported our family for six years,” she said. “The people and teachers there helped us raise our children.”

When it closed in March, they continued to pay the center in April “without question,” she said.

She and her husband carefully weighed the risks and benefits of sending the children back, doing research, and going through what she described as a “roller coaster of emotions.” Ultimately, the benefits won out. She took her 3-year-old and 1-year-old back to Childspace on July 2, the day her 6-year-old started his summer camp.

“Anna [the 3-year-old] was most articulate about that,” Nikoo said. “She said, ‘I miss my teachers and my friends.’ We had real concerns about whether we were making the right choice ethically and through a public health lens, and we decided the pros outweighed the cons. We want them to be playing and coloring and running through the sprinklers.”

Childspace impressed her with its “comprehensive plan” for reopening and how the center “balanced safety concerns for the children and all staff and teachers with an eye toward what it means to be a child in this moment.”

Regarding St. Mary’s, the Jackells went through a similar process in making their choice to send Adrian back.

While Rob Jackell wants his son “to get back on track for reading and writing and everything else,” he said, he thinks that “the most important thing right now is for kids to remember what it’s like to be with other kids, how to play and function and socialize. That’s number one. As much as I wish it were academics … it takes a back seat right now.”

The city should be “prioritizing child care and schools,” said Mara Jackell. Rob adds that as important as business is, Philadelphia should not be opening up its bars and restaurants, especially because they can accelerate the spread of the coronavirus.

“Prioritize getting the numbers down low enough that we can safely open schools in September. And honestly, they need to spend some money on it – we can’t be having budget cuts right now,” he said.

Both agree that the mayor and governor need to do more to support child care and early childhood – it’s tough given the pandemic’s impact on tax revenues, but necessary, the Jackells assert.

“The mayor and the governor both have emphasized what people have to do and very little about what they’re going to do to help us,” Rob said. “The economy can’t function without health care and education.”

At St. Mary’s, amid all the technical and procedural challenges, staff members say they’re trying to keep the warm and loving attitude that puts children at ease.

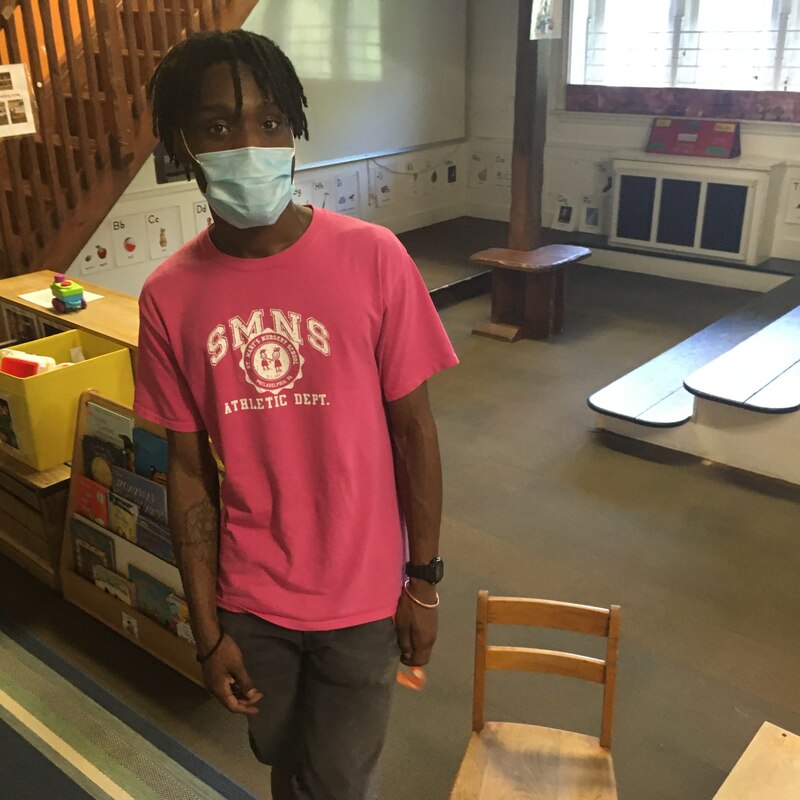

“I just stay positive, keep an open mind,” said teacher Andre Houslin. “Keep it very simple, relating to the kids as best I can. … This pandemic has been a lot for them, so getting them to talk about their emotions and how they feel is one of the biggest things to me.”

St. Mary’s teacher Andre Houslin in his newly organized classroom. (Photo: Bill Hangley)

His colleague, teacher Genevieve Abaara, added that the center will do its best to balance strict social-distancing rules with the need to make kids comfortable. Staff are replacing hugs with jolly waves and greetings, she said – and as long as the kids feel the love, they don’t mind the change.

“The fact that we’re still interacting the way we normally do, even though we’re not in close contact, that’s big for them,” said Abaara. “We’re not isolating them.”

Childress, St. Mary’s director, knows the challenges have just begun, but she hasn’t lost faith. She tells her staff that if they stay honest and open, the center and its kids can ride out the storm.

“I keep saying to my staff, our approach is to be transparent,” she said. “I don’t know if we’ll make it through this year, but we’ll do our best.”

The Notebook’s coverage of early childhood education is funded by the William Penn Foundation.