Philadelphia teachers are weighing a job action as contract negotiations have yet to yield an agreement.

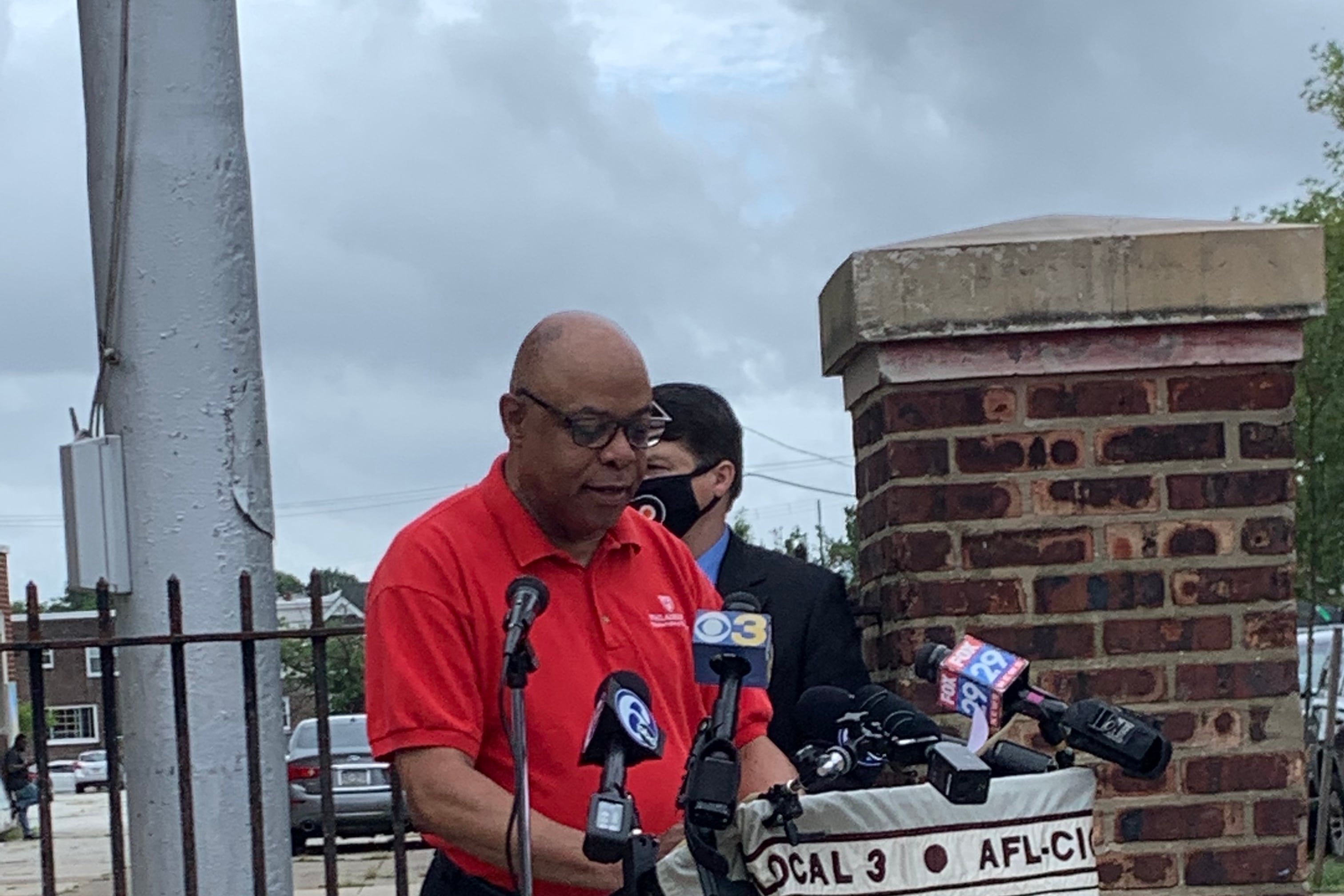

Teachers in the school district have been working without a contract since Aug. 31 and are seeking a one-year extension with what Philadelphia Federation of Teachers President Jerry Jordan has called a “modest increase” in compensation.

On Monday, Jordan emailed his 13,000 members, which also include secretaries, counselors, nurses and paraprofessionals, and raised the possibility of a “work to rule” action in which they would do the minimum required within school hours under their now-expired contract. He sought members’ input on such a move.

How “work to rule” would play out while educators and students are teaching and learning remotely is not known.

Last month, Jordan said that the district was trying to “shake down” the teachers by insisting they sign off on a plan to reopen school buildings before discussing a possible pay increase. At the same time, however, he asked his members for a two-week window to continue negotiations and reiterated that he considered a strike or other job action to be a last resort.

Without divulging details, both Jordan and Superintendent William Hite said at the time that they were hopeful about reaching an accord, although they disagreed about whether the district could afford to raise teacher salaries.

Now, following more than a month without an agreement, the rhetoric is ramping up. The district is planning to reopen school buildings under a hybrid learning plan in November, after going fully remote in March and starting the year exclusively online.

“Compensation is the outstanding issue,” said the union’s legislative affairs director Hillary Linardopolous in an email to Chalkbeat.

Before COVID-19, the perpetually cash-strapped district was planning to end fiscal 2020 and 2021 with money in its coffers. But due to a plunge in state and local tax revenue as a result of the pandemic, it is now forecasting a shortfall exceeding $800 million by 2025 to maintain its current level of service and pay additional COVID-19-related costs.

“We know the district has the funds to secure steps, lanes, and across-the-board wage increases for a one-year extension,” Linardopolous said. Steps and lanes are the increases teachers get for accumulating additional years of experience and advanced degrees.

She noted that other city unions have negotiated raises this year. The police union received a 2.5% increase, while AFSCME District Council 47, representing white collar workers, and District Council 33, representing blue collar city workers, each got 2%.

The Board of Education, which governs the district, has no taxing power and relies on the state and city for almost all its revenue. In February, Mayor Jim Kenney had sought a small increase in the property tax rate to help the schools, but the city council never took up the proposal.

When the district was under state control, teachers were forbidden from striking and they went without a contract for more than five years. During that period, salaries were essentially frozen, and many teachers never made up the difference they would have received for additional experience and education. Partly as a result, teachers salaries in Philadelphia, once among the highest in the region, have fallen behind surrounding districts.

This is the first contract being negotiated since the district returned to local control in 2018, ending 17 years under the state-dominated School Reform Commission.