Black boys are unarguably the most vulnerable population in our school system.

They are suspended and pushed out of schools at a higher rate than any other student population. They are disproportionately likely to find themselves labeled as needing special education services. They are more likely to drop out of school, are incarcerated at a higher rate than their teenage peers, and are less likely to have post-secondary learning experiences.

It should be no surprise to see educators pursuing drastic reforms, including establishing single-sex schools, to counteract these effects. These initiatives are great. But it is also up to educators to come up with solutions for the thousands of black males in urban public schools who do not have access to these initiatives.

I’m suggesting we take the pressure off of individual teachers and parents and focus on advocating for — and building partnerships to create — more literate communities.

Too often, black males students’ schools and communities give them access only to uninspired, rote literacy experiences. The students are less likely to have access to literary field trips and experiences like plays, poetry slams, library visits, author visits, and drama clubs.

Many black males live in communities where most black-owned bookstores with specialty titles have closed. They are less likely to find either larger chain or indie bookstores within a close distance of their communities. They do not have access to book festivals, large or small.

In schools, the “book deserts” can be even worse. Additionally, school-level policies, like rules restricting students to checking out one book per week, can reduce students’ opportunities to develop vocabulary and explore different genres.

Black males in urban settings are also more likely to find themselves in financially strapped schools where leaders have scrapped Reading Recovery services or the reading specialist. Their teachers may not have access to training focused on on motivating children to read.

Ironically, literacy is not always the focus or specialty area of school leaders. This can lead to buying “teacher-proof” materials, instead of using funds to inundate the school with books, magazines, and nonfiction audio, print, and electronic materials.

We know all of these issues exist. But as report cards roll around every year, black males are made to pay for this inequality.

They are made to pay with comments related to their “grit.” They are made to pay with frustration about their lack of progress expressed by teachers, parents, and administrators. They are made to pay with behavior referrals as pressured teachers lose patience. They are made to pay when school administrators eliminate recess or when schools limit recess to 20 minutes instead of a full hour. They are made to pay by being forced to do rote tasks instead of having interesting, inspiring literacy experiences.

The real issues here are inequality and the fact that many black males live in book deserts.

Literacy professionals like me see that the lack of authentic literacy experiences eliminates the motivation for black boys to read. Those issues lead black boys to get bored, and then they are pushed out of school through suspensions. The emotional toll that this takes on many black males who fail at literacy should not be ignored.

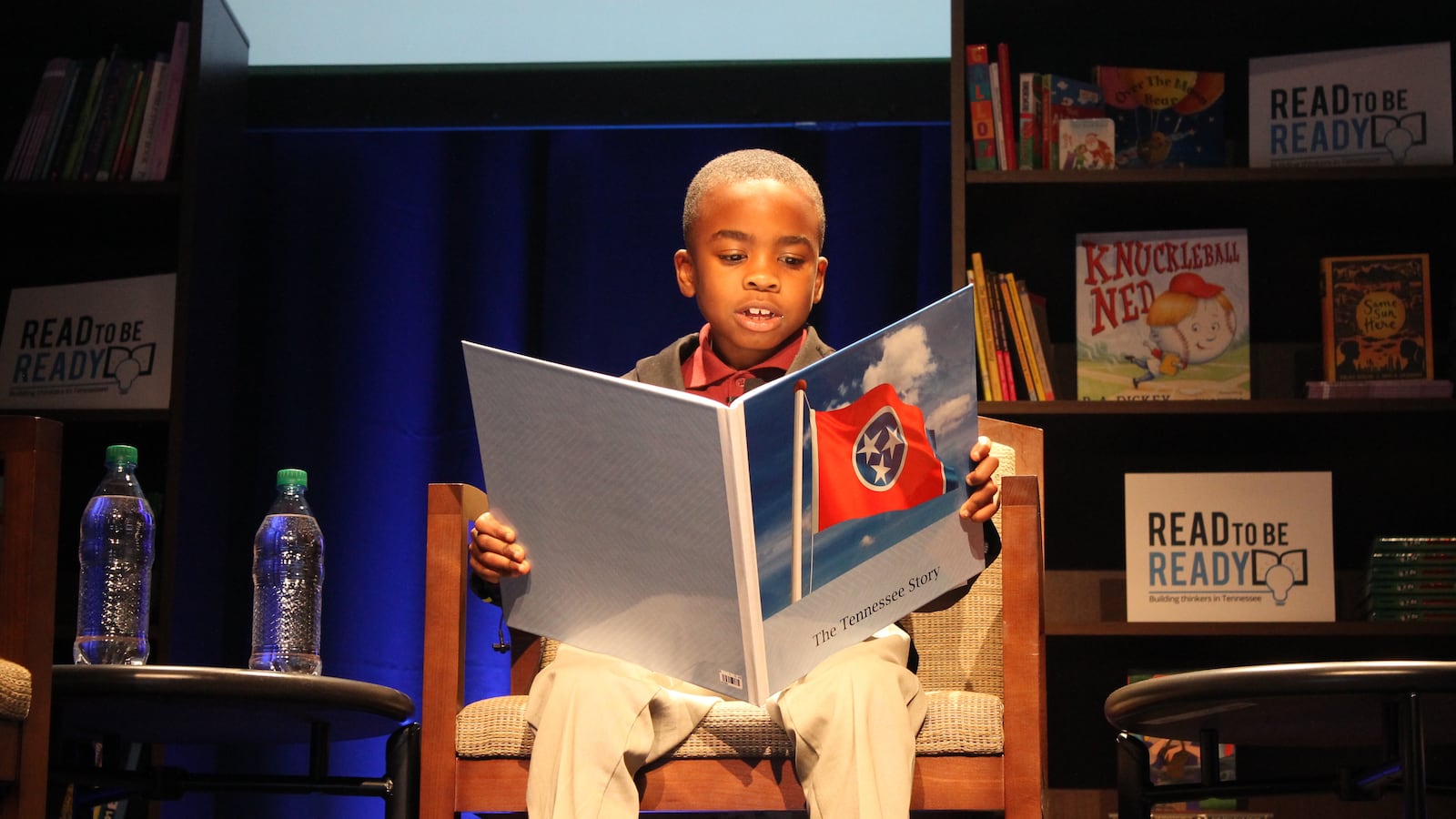

It is time to reclaim authentic literacy that inspires and motivates black males. Black males need access to books which reflect their experiences and motivation in the form of purposeful and leisure reading. We know leisure reading, and the freedom to exercise choice in reading, are what inspire children to read when no one is looking. These opportunities can also inspire black males to read and recite their favorite poems and make up their own.

There are so many ways to inspire black males to read. Equally important are:

- the social justice framework, or using news stories, essays, speeches, and biographies focused on real community issues that need to change

- debates and town hall meetings, where black males can use critical thinking and discuss topics such as police brutality, sports, friendship, family issues, and tragedies

- the ethnic studies approach, in which black males learn black history narratives and events, which allow them to develop a passion for learning who they are in relation to the greater world.

As we embark on a new school year, we must do so with the idea that we have the power to change this reality. Book deserts in urban communities can be eliminated as easily as they were made in the first place. Our advocacy efforts must be community wide, district wide, school wide, as well as in local classrooms.

We must do our part to forge community partnerships to change this reality — or black males will continue to be treated as both victims and perpetrators of their own reality, and punished for being both.

This piece first appeared on Literacy & NCTE, the blog of the National Council of Teachers of English.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.