A Milwaukee high school student walks into his class on “Romeo and Juliet.” But there’s no teacher walking students through Shakespeare’s turns of phrase and no peers to discuss them with.

Instead, “The student toggled between his phone and the lesson on the screen, texting while the lecture played and talking to a student nearby,” researchers who observed the course recorded. “The instructor came by and told him to take notes, but he did not follow through.”

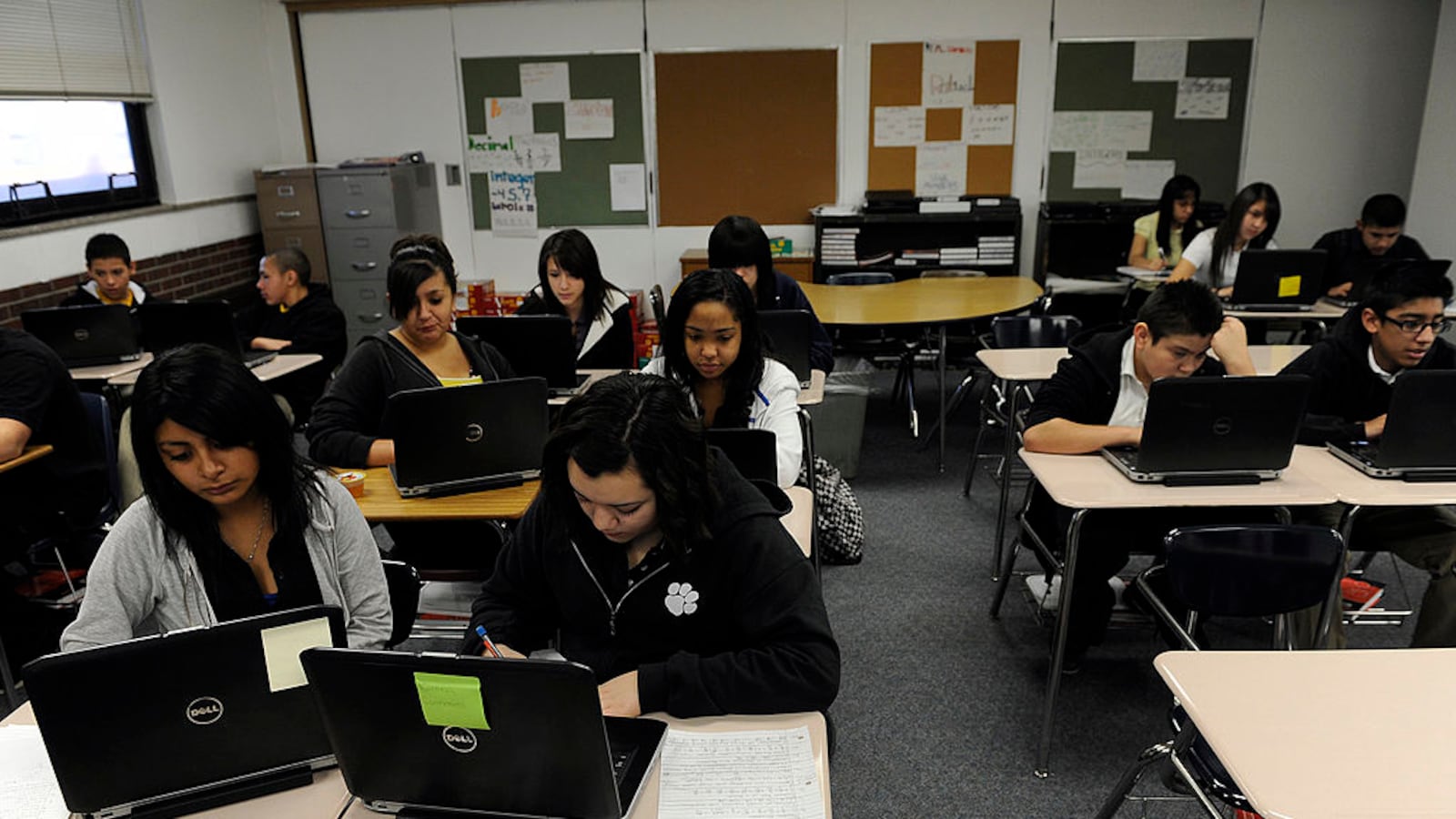

Welcome to the world of online coursetaking, where regular public high schools farm out some instruction to computer programs, often in an effort to help students rapidly earn course credits. In Milwaukee, one in five credits earned in middle and high school in the 2016-17 school year came through an online class.

New research finds the approach does help students graduate — but raises big questions about whether it actually helps them learn.

Researchers who spent years watching students take online courses in 18 Milwaukee high schools found teachers struggling to monitor large groups of students, classes that effectively segregated students with behavioral problems, and students habitually searching the Internet for answers. Taking the classes also appeared to actually hurt students’ year-end math and reading scores.

The research underscores the risks of allowing students to accumulate credits through online courses, a practice that appears to be spreading. Edgenuity, which created the program the Milwaukee students use, says that 4 million students use its programs each year, though not exclusively for credit recovery.

A spokesperson for the Milwaukee Public Schools did not respond to a request for comment, but both the district and Edgenuity tout their partnership. And some educators report that the courses offer valuable second chances, keeping some students in school who might otherwise drop out.

“Online learning, whether implemented within a school, virtually, or both, empowers and benefits students,” Edgenuity spokesperson Lauren Nussbaum said in a statement.

Accounts of similar programs in San Diego, New Orleans, and the Florida Panhandle have found similar issues as the Milwaukee researchers, though, with students appearing to gain little from the course recovery work. The results offer one potential explanation for the increasing disconnect between high school graduation rates, which are rising, and federal test scores, which are largely stagnant.

“These are dangerous programs because they scratch itches you want to scratch and it is hard to feel the damage that they do,” said Nat Malkus of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, who has studied credit recovery programs.

In Milwaukee, researchers find steep challenges, frequent cheating in online classes.

Most U.S. high schools now offer some form of credit recovery, often via an online program, though estimates vary on what share of students participate in such programs each year. One analysis from the 2015-16 school year estimated that 15 percent of high school students did, while another found that it was just 6 percent.

There is also evidence that these programs are more frequently used in high-poverty districts like Milwaukee. There, most of the online courses taken were core academic classes like math and English, though some students also took elective courses.

In a new peer-reviewed study, Vanderbilt and University of Wisconsin researchers examined those classes from the 2010-11 school year through 2016-17. Visiting schools, they watched students take in video lessons and then answer questions to show what they had learned, usually under the supervision of a teacher during the school day.

But it was difficult for the teachers to offer thorough supervision, much less teach, they found. Class sizes were large, and teachers spent much of their time helping students log in to the system and maintaining order. Teachers also struggled to help students with disabilities or English learners, many of who encountered challenges using the programs.

Their job was especially difficult because the students were all taking different classes, many of which were outside the teachers’ subject area.

“As a non-math person, I find it difficult,” one teacher explained. “I can do it if I watch the whole video, but I don’t have the time to watch the entire video to answer the questions with a student.”

Students enrolled in online courses entered with lower test scores and were absent for more days than other students in the district. Many of the students had unique circumstances, like being teen parents. Students with behavioral problems were often placed into online courses, too.

The classes were a “dumping ground,” a number of teachers said.

Some teachers worked intensely to help students, but others were open with their negative attitudes or low expectations. When one student came into the classroom and slept all period, an instructor indicated that she was 19 and would probably “just sit here until she is 21 and will call it a day.”

At one school, one teacher was “effectual and engaged, while another sat in a corner working on his own stuff, and a third just gave the students the answers,” the researchers observed.

A spokesperson for Edgenuity said that schools can guard against cheating by with settings that disable other tabs or browsers while students are working through the program.

“Edgenuity’s digital curriculum is used successfully in a wide variety of online and blended learning models, and is designed to be implemented with qualified teachers to facilitate student learning,” said Nussbaum.

The researchers said the district has made efforts to improve the quality and rigor of the online courses, including limiting courses taken by ninth and 10th graders and trying to tamp down on cheating.

Students may benefit from easier path to graduation — but that raises bigger questions.

Edgenuity, which has received hundreds of thousands of dollars in contracts with Milwaukee Public Schools, has described its partnership as a “success story.”

Indeed, in a separate study, some of the same researchers show that online courses seem to be achieving their key goal of helping students graduate in Milwaukee. The effects were quite large: students who took an online class were 13 percentage points more likely to graduate than similar students who didn’t.

From a student’s perspective, that’s a good thing. And teachers told researchers that the online courses offered real benefits.

“Teachers and other staff suggested that if it were not for the online course-taking option, some of these students would not be in school at all or would be disruptive in the regular classroom,” the study says.

Still, the researchers’ observations suggest that the students there may not be experiencing much actual learning. Of course, instruction in many traditional high school classes might not hold up to detailed scrutiny, either. But the study also finds that the online classes may have hurt Milwaukee students’ year-end math and reading scores — a finding that’s consistent with research on online credit recovery in particular and virtual instruction in general.

The findings are especially significant at a time where states’ graduation rates are increasingly disconnected from their students’ test scores. An analysis by Malkus of AEI found that graduation rates had increased at slightly higher rates in high schools that had more credit recovery programs.

“If you keep kids that would otherwise not graduate, it’s hard to argue that’s not a good thing,” he said. Still, he added, “The dangers come in a number of forms: Did we allow some of those kids shortcuts so they didn’t learn some portions of these courses?”

This story has been updated to remove reference to an analysis by Edgenuity purporting to show higher course passage rates by students who used the program for credit recovery. That report compared students taking an in-person class to those in an online Edgenuity course. But it only included those Edgenuity students who completed certain class activities with a passing grade or who were marked to have completed the course by a teacher; it did not use the same approach for students taking in-person classes. That likely led to a slanted comparison.