As teens, Page Valentine Regan and Robyn Tomiko felt like they couldn’t be fully themselves inside their school buildings. Now, these queer educators work to make classrooms welcoming spaces for all students. Below, they reflect on their personal histories and the work that lies ahead.

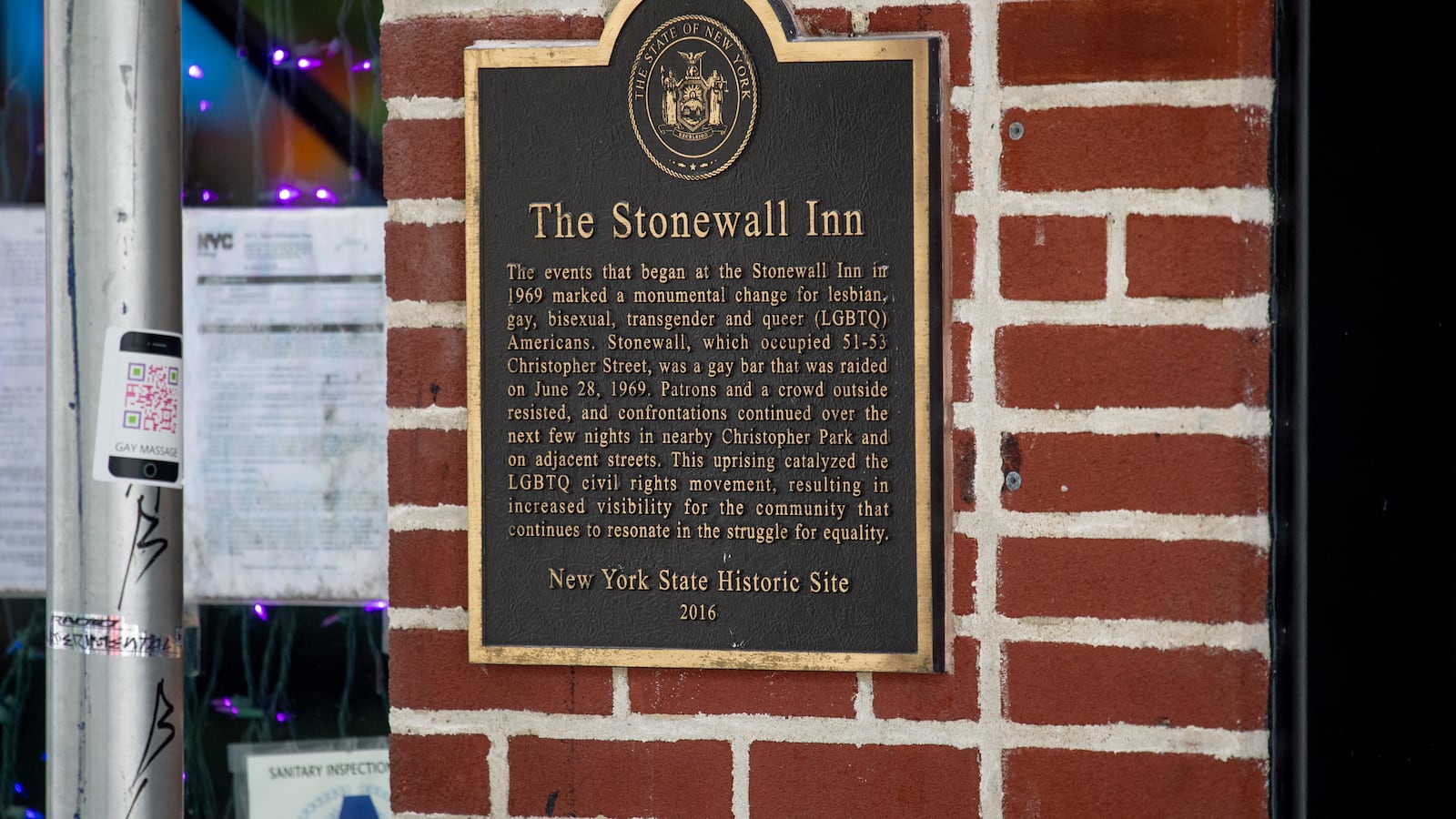

PAGE VALENTINE REGAN: In a brief and subtle nod to the history of LBGTQ+ rights, my 10th grade teacher put Stonewall on the list of possible topics for group projects. I chose it, and although it was cool to have the option, the outcome remained impersonal and held queer identity at a distance — an “issue” rather than a point of pride or awareness about my 16-year-old self.

I always knew that my gender expanded beyond the scripts I received as a child, yet, growing up in Denver, the only exposure I had to anything remotely similar to my experience was the documentary on the devastating Brandon Teena story that I came across at the local public library. Brandon was brutally assaulted and murdered because he was transgender. Thus, to live authentically, my only options seemed to be spontaneously waking up in a boy’s body, as I had long prayed for, or death.

ROBYN TOMIKO: I graduated high school in 2000, and there were zero queer kids in my school. Not one in the whole rowdy bunch of us. Not even among the 150 staff members was there a hint of queer. For the first 37 years of my life, and until I came out to my parents, there was not one queer person in my family. This was the only “truth” that folks in our small, conservative Texas town could handle.

In reality, at school, all the queer kids clumped together in the safe alcoves of the hallways. We were kept under wing by our theater teacher, who had a “roommate” who would bring her lunch. We’d occasionally let slip our fancies and proclivities in front of the wrong company and get cornered in the auditorium or behind the tennis courts. For the most part, though, our secret club was kept safe. And quiet.

More than two decades on, I now teach middle school 15 minutes away from where I grew up. There are a few kids who choose to be visibly queer where I teach; there are out teachers, too. I’m allowed to wear a rainbow-colored lanyard to hold my badge. I’m even allowed to acknowledge the existence of LGBTQ+ people and topics, so long as I’m careful. It can be tricky, given that Texas is one of a few U.S. states that still has a so-called “no promo homo” law, limiting how teachers can talk about LGBTQ people and issues.

If I introduce a text that has queer characters or families, or if I hold a Socratic seminar on how character development is influenced by gendered expectations, I have to be prepared to defend the material to school administrators should parents complain. I’m not one to shrink at pushback or questioning of my instruction; I just don’t want to get fired.

In 2014, Brett Bigham, an Oregon Teacher of the year, lost his job after coming out publicly as gay. In 2017, one Texas teacher, Stacey Bailey, was put on leave after showing her elementary art class a photo of her and her fiancee; three years later, Taylor Lifka was suspended in a Texas border town for displaying Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ+ posters in her virtual classroom. Even though the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County now ensures that I won’t be fired simply for being gay, I’m still not able to post a photo of my girlfriend in my classroom or discuss what might be construed as a “homosexual agenda,” whatever that is.

So, I choose to “queer my instruction” the best I can within these confines. When addressing my students, I use “friends and folks,” rather than “ladies and gentlemen”; I offer my pronouns upon introduction, and I no longer write or read aloud she/he without adding /they. I hold Socratic seminars on what it means to be a “good guy” or a “bad guy,” and then ask students to label Batman one way or the other. The discussion is less about Batman and more about seventh graders recognizing the duality of human nature and questioning society’s rules for what counts as “good” or “bad.”

PAGE VALENTINE REGAN: As a component of my work with a southern nonprofit, I contributed to district-wide efforts to make schools more accepting and affirming of gender and sexual diversity. Research shows that using a curriculum that includes LGBTQ persons, training teachers in the diversity of these identities, and providing safe spaces (places where students can express themselves and be free from trauma) contributes to less discrimination and greater educational aspirations for students.

On one occasion, I was brought in to teach a lesson on gender to a second grade class. Given the presence of a recently out transgender student, the school requested the session to help students better understand the child’s transition. Twenty-five children participated enthusiastically when I had them move along a taped off ‘gender spectrum’ in response to a series of prompts. One end of the line was pink, the middle purple, the other end blue. The students clumped together for certain prompts like “trucks” and “Barbies” at respective, stereotypically gendered sides, while words like “salad” and “Legos” revealed more nuance. One student, in response to “Barbies”, remarked, “If boys like Barbies, my dad says that means they’re gay.” In our reflections after the activity, I asked the students if they knew about the word gender; in response, a cisgender girl in the class pointed to the out transgender boy, and said, “we have that problem.”

Clearly, my lesson was not enough. While the administration at the school felt satisfied that we “tried,” I went home feeling like I had failed the transgender student and his classmates. What might it have looked like for me to be called in as a collaborator charged to work with the classroom teachers who valued their students’ evolving understanding of gender? What needs to be in place so that students aren’t seen as “problems” that need fixing?

ROBIN TOMIKO: Few things move me to the level of passion and ire I feel when I consider that my students in 2021 are still experiencing the silencing and violent disregard that I went through 30 years ago — and that my idols experienced decades before that.

Not knowing exactly how to change things is frustrating, debilitatingly so sometimes, but queer kids won’t benefit from my surrender. So I keep learning. This summer, I’m attending professional development focused on “queering” educational spaces. My hope is to learn and unlearn with like-hearted humans devoted to this work. In some ways, I’m still that queer kid, huddled in the auditorium, the only gay person in my family, trying to keep my life quiet. But I also know now that I have more to give.

PAGE VALENTINE REGAN: Our stories align with our mission to continue leaning into what “queering” school spaces can look like. When we think about queering classrooms, we do not mean mere inclusion or visibility; rather, we invite students to question what’s “normal.” Asking students why certain rules are in place also opens up the dialogue about race, ability, and how clinging to “traditional” ideas limits students’ capacities for authentic expression and full lives.

We often hear questions from educators like “What if we say the wrong thing?” and “What if parents pull their kid out of our school?” And these concerns are valid. There are always risks involved in “doing the work.” Yet we hold onto the hope that if we, as teachers, listen to students and continue to challenge the status quo in the ways we can, the classroom will remain ripe with possibility.

Robyn Tomiko (she, her, hers) is a middle school English teacher in Texas and an advocate for educational equity. She will begin a doctoral program in the fall to explore the ways public education can function in the service of social justice.

Page Valentine Regan (they, them, theirs) is a former coordinator for after-school programs for queer young people. They are currently a Ph.D. candidate exploring the complex ways that transgender and non-binary emerging adults of color navigate love.