As teacher educators and historians who study American education, we know that how and what we teach students about race has been controversial and contested for centuries. Progress is frustratingly slow, and the forces of retrenchment and reaction are always present. Yet some victories, even seemingly small ones, can be meaningful and build momentum for broader change. With that in mind, we feel it’s time for teachers and textbook makers to capitalize the “B” in Black and teach the 143-year (and counting) struggle behind it.

The rationale for “Black” when referring to the racial group is as simple as it is compelling. It recognizes the distinct and vital roles that people of African descent have played in American society. In author Lori Tharp’s words, using the lowercase “b” is “in effect deleting the history and contributions of my people.”

For educators, teaching the foundational place of Black history in the history of the United States is essential, as is teaching about the evolving nature of our everyday language. Capitalizing Black opens opportunities to engage with Black history and learn valuable lessons about how social change is made.

The movement to capitalize is not new. In 1878, just after Reconstruction, Ferdinand Lee Barnett wrote the article “Spell It with a Capital” in his newly established newspaper, The Chicago Conservator. Barnett, who would later marry the American investigative journalist Ida B. Wells, was referring to “Negro,” the prevailing term of the time that has long been spelled in the lowercase. In the same vein, Edward A. Johnson noted in his groundbreaking 1894 textbook, “A School History of the Negro Race in America, from 1619 to 1890,” “I respectfully request that my fellow-teachers will see to it that the word Negro is written with a capital N. It deserves to be so enlarged, and will help, perhaps, to magnify the race it stands for in the minds of those who see it.”

W.E.B. DuBois followed this lead in his first book, “The Philadelphia Negro,” staking his argument for the capital “N” in a first-page footnote: “I shall throughout this study use the term “Negro,” to designate all people of Negro descent … I shall, moreover, capitalize the word, because I believe that eight million Americans are entitled to a capital letter.” DuBois would go on to co-found the NAACP and, through his personal correspondence as well as the organization’s decades-long letter-writing campaign, lobby publications like the New York Times and the New Republic to standardize “Negro.” By the 1950s, concerted pressure had made this common usage.

The 1960s was an era of changing racial consciousness, and the terms “Negro” and “black” overlapped in the popular discourse. Dr. Martin Luther King used both in 1963’s “I Have a Dream” speech, but as the decade moved on, “black” and “Black” typically indicated a more activist and change-oriented mindset as well as a way of proactively redefining racial solidarity. The matter of capitalization varied, though. Kwame Toure, known previously as Stokely Carmichael, popularized the phrase “black power” and used the lowercase throughout his book of the same name. Conversely, the Black Panthers’ “10 Point Program” used the capitalized phrase “Black People.”

Among student activism movements of the time, there is similar variation, but many already regularly employed the capital “B.” The University of North Carolina’s Black Student Movement and San Francisco State’s Third World Liberation Front both capitalized the B in 1968. The Black Student Federation, a high school student movement that led an anti-segregation walk out of Boston Public Schools in 1971, also used the capital B.

While the fight for capitalization has stretched well over a century, our schools and the major textbook publishers have been slow to adapt. All of the three largest companies’ most recent high school-level American history survey texts use “black”: McGraw-Hill’s “Unfinished Nation,” Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s “American History,” and Pearson’s “The American Journey.” “The American Yawp,” a popular scholarly, free, online textbook, just revised its text to “Black” last fall.

So when we capitalize Black in our classrooms, by editing our textbooks and updating our handouts, we join a long tradition of educators, intellectuals, and activists who have evolved our language in order to change our world. And when we teach our students why we have made this change, we demonstrate how Black history has shaped our lives and invite students to inquire further.

As we make this shift, we need to use Black and other race identifiers as adjectives, not nouns. We should also strive to be as specific as possible, noting nationalities, ethnicities, and other identities particular to the people being studied for accuracy and to resist stereotyping. For instance, “Asian” is a category that covers over four billion people, so indicating precisely that we mean Koreans or the Uyghurs of China or Kurds spread across several countries is important. Finally, it is vital to acknowledge that all peoples are racialized, and we should also capitalize the “W” in White so that we don’t implicitly make White people the default or the aspirational “people without a race.”

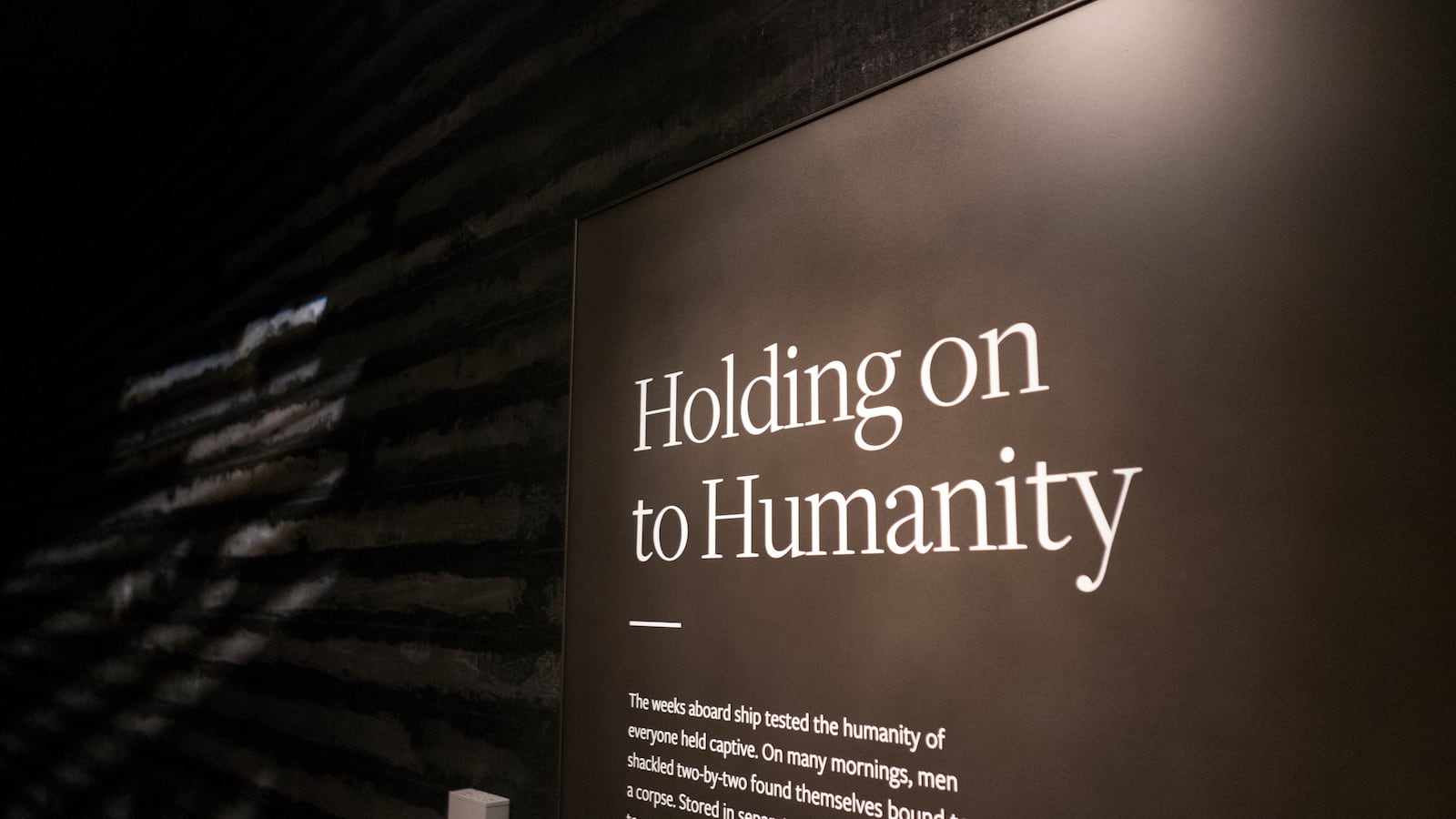

Capitalizing the “B” in Black isn’t just a typeface change in our classrooms. It is a milestone within a long historical struggle for oppressed people to self-define and assert their humanity in the face of racism. And when our students engage with this past, we invite them to take part in its future. Our young people must learn that how we refer to ourselves — our racial identities, our pronouns, and beyond — is powerful; it is an act of self-naming in the pursuit of freedom. As the historian Nell Irvin Painter so eloquently put it, “Spelling may not change the world, but it signals willingness to try.”

Charles Tocci is an assistant professor of education at Loyola University Chicago and co-author of “The Curriculum Foundations Reader.”

Michael Hines is an assistant professor of education at the Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, and author of the forthcoming book, “A Worthy Piece of Work: The Untold Story of Madeline Morgan and the Fight for Black History in Schools” from Beacon Press.