Four.

That’s my score on the Adverse Childhood Experiences survey, or ACE. Four is also a relatively common score. One in six adults has an ACE score of four.

The original ACE questionnaire asks 10 questions about childhood trauma. The questions gauge a person’s experiences with such traumatic events as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, parental neglect, and the mental illness or incarceration of a member of their household. ACE scores range from 0 to 10, and each endorsed question counts as one.

A score of four or more correlates with an increased likelihood of facing mental health challenges, financial instability, and adverse health outcomes, and it ups a person’s chances of partaking in risky behaviors in adulthood. There is no ACE score that necessarily leads to specific outcomes, bad or good. But the higher the ACE score, the greater the negative impact tends to be on adult life.

Sometimes, my ACE score makes me angry and makes me wonder how my life would be different if my upbringing had been different. At the same time, it gives me insight into my role as a public school psychologist and better equips me to support students facing trauma. (Three of four high school students have an ACE score of at least one, and one of five report a score of four or more, numbers not likely to surprise today’s educators.) Plus, I’m not sure if I would have even entered this field if my upbringing were different.

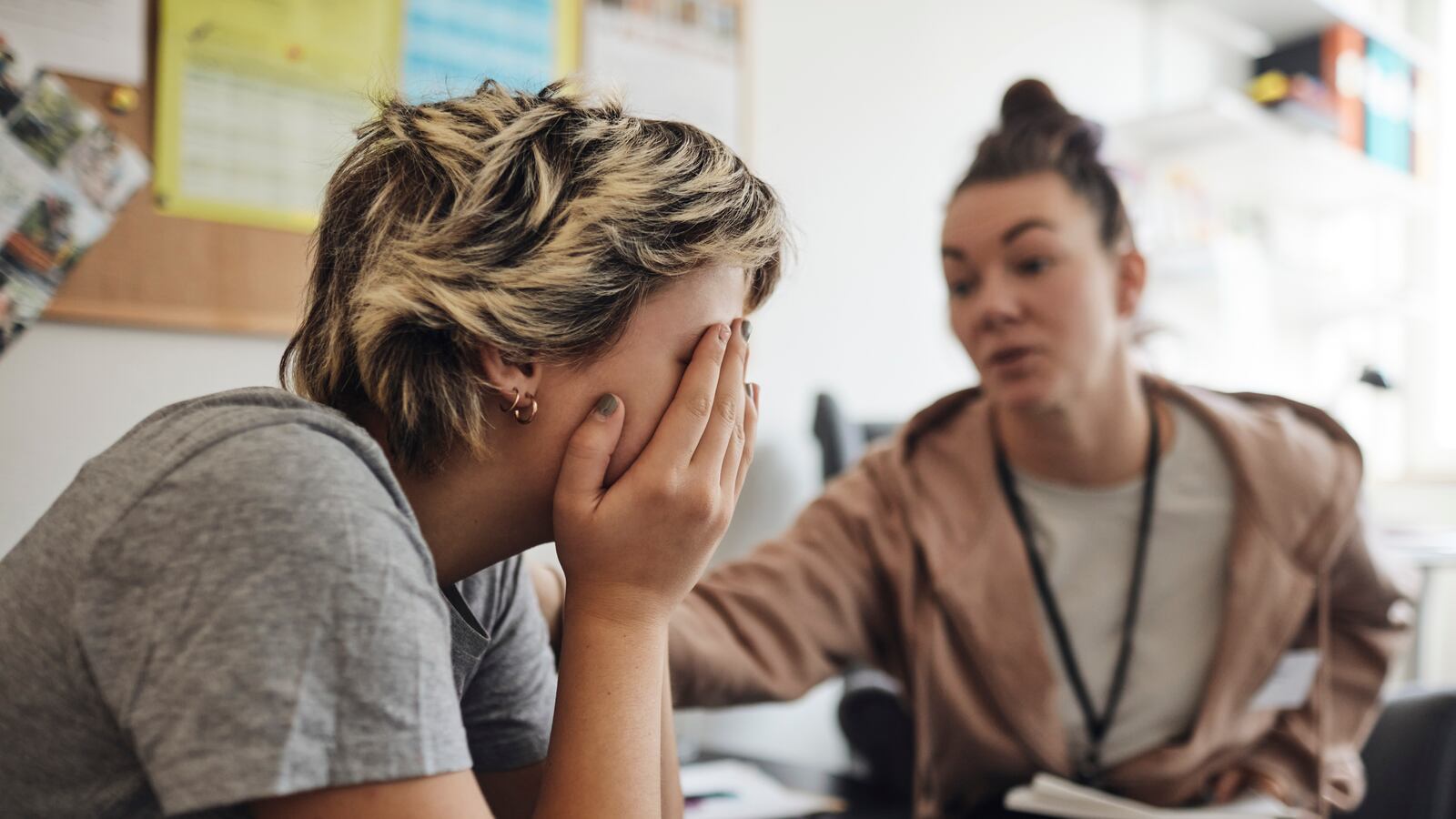

Educators know that when kids step into schools, it’s not just about teaching them core academic subjects. It’s about providing a safe, supportive environment, and sometimes giving that little extra attention to those who need it. Plus, supportive, engaging classrooms can help students work through adversities.

As a school psychologist, I frequently have the privilege of providing that little extra attention to students. In doing so, I often learn about a student’s traumatic experiences.

In one-on-one settings, school psychologists help students complete self-assessments of their social-emotional/behavioral well-being, and those experiences really open the conversation. I might ask, “Would you say you never, sometimes, often, or almost always feel happy to be at school?”

I recall one student’s answer: “I guess often, I’d rather be here than home. But I still don’t like reading.”

“Do you want to talk about what’s going on at home?”

His mom worked a lot, he told me, and he had to take care of his younger sister when he’d rather be on his scooter with friends. He’d talk about how his mom had a new boyfriend and it was going just “OK.” His father was in prison, but he was supposed to talk to him on the phone the following week. Then, he asked, “Do you have any snacks? I’m starving.”

And another student’s response: “I hate it here, I feel like I can’t get a break.”

“Tell me more about what you’d like a break from.”

This student shared how the pressures of school and getting good grades were hard to juggle while also feeling hungry for both a good meal and affection most nights at home.

If I could change traumatic experiences for these kids, I would. I think we all would. But I’m not sure I would change my own ACE score because it helped lead me to become a school psychologist.

When I reflect on my own experiences in schools, I am grateful to see how far things have come. I’m grateful that more public schools are acknowledging the importance of mental health and amplifying what’s available under the umbrella of special education services. At the same time, I’m terrified for students without access to these types of services. The opportunity to support young people at a time when so many are struggling feels like a gift and one that I hope continues to evolve with the needs of our students.

Brittany Lewno-Dumdie, Ph.D., NCSP, is a school psychologist in Washington state. When not working with students, she enjoys writing about school experiences, school psychology, and strategies for helping students.