As AI dominates the education zeitgeist, I think it’s time to highlight an effective teaching tool as tried and true as a Ticonderoga No. 2 pencil: high-quality IRL relationships with students.

I learned this first — and best — from my high school Spanish teacher, who, as the matriarch of the Spanish department, went simply by “Señora.”

Señora started class with “Qué hay de nuevo?” (What’s new?) She learned what had happened at our most recent swim meet, band concert, or football game. She laughed as she gently unearthed the chisme (gossip). I loved this part of class. It seemed so useful, like I was actually learning to speak Spanish, and it involved one of my favorite things, talking.

Years later, when I became a high school Spanish teacher, I understood Señora was up to something deeper than building conversational Spanish skills.

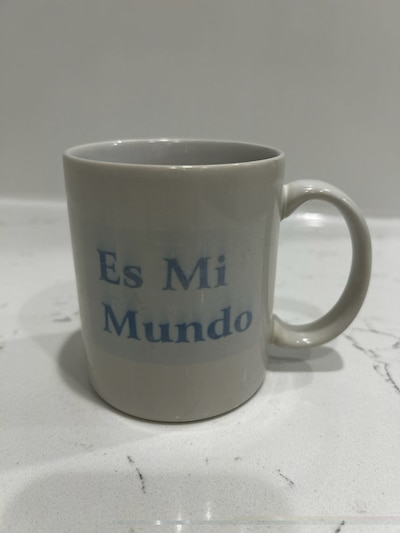

She held court over those sessions, sitting atop her tall stool, sipping coffee from the mug with two of her favorite sayings, “Es mi mundo” (It’s my world) and “Todo es posible, nada es seguro” (Everything is possible, nothing is certain). All the while, she was busy taking mental notes on which students were uncharacteristically quiet, who hadn’t slept, who wasn’t OK.

We also learned Spanish. I remember my brother telling me how he announced to Señora’s whole class that he had taken a shower with a Japanese man, confusing Japón with jabón, the word for soap. That lesson stuck.

Some of my favorite class periods involved the slide projector. On those days, we would join Señora on her travels across Latin America, like the time she navigated border crossings as the official interpreter for an Airstream caravan tour. We’d listen, rapt, about her trip to Machu Picchu during which — you won’t believe it — she slept in the ruins. From our desks in a random Wisconsin public high school classroom, we gallivanted through Amazon waterfalls.

Senior year, having exhausted our school system’s Spanish progression, two friends and I asked Señora to teach us “Spanish 6.” Without pausing, she said “¡Sí!”, voluntarily giving up her planning period for us.

Only after becoming a teacher did I recognize Señora’s level of sacrifice.

Each day, fourth hour, we’d sit in a fishbowl cubicle in the library. On Wednesdays, we worked from the “Book of Questions,” asking and responding entirely en español. I learned Señora’s opinion about soulmates (good for frolicking through the aforementioned Amazon waterfalls, not for unloading the dishwasher or changing diapers), tattoos (always regrettable), and travel (¡por supuesto!).

Señora was ever present with us, existing in the physical world of pencils and people and spending exactly zero momentos chasing ed tech hacks that would “transform” her teaching. Her ace was building relationships with and among her students, deploying the original AI — Authentic Interactions — to forge real connections.

I was in college when cancer forced Señora to leave the profession prematurely.

More than half a dozen years into Señora’s illness, her classroom storage closet remained exactly as she left it. Por si acaso — just in case.

“For when she comes back,” the other Spanish teachers said.

I know because I got to visit it. By then, I was teaching Spanish. Señora knew she wouldn’t teach again, so we planned to meet at her classroom for the official baton pass when I was home for a visit.

But time and life being what they are, months passed before I made it home again. By then, Señora was bedridden. Señorita Jolley would let me in, she told me. And “take anything you’d like.”

I called a close friend who was also in town. I wanted una amiga with me.

Only after becoming a teacher did I recognize Señora’s level of sacrifice," writes Becca Katz.

In the time capsule closet, we sat amid Señora’s belongings. Piles of papers, decades of planners, and dozens of meticulously labeled manila folders with handwritten transparencies and photocopied, handwritten worksheets shared shelves with books, lesson plans, and slides. Crisscross applesauce on the closet’s green linoleum floor, we sifted through the layers.

I assembled original copies of her worksheets and transparencies, hoping the cursiveish font de Señora would buttress my confidence in a room full of discerning high school juniors. My friend assembled Señora’s books and posters of Spanish art. I added her 1998-99 planner to my stash, sentimentally marking our graduation year.

As we were leaving, I remember seeing her mug — the one with her favorite sayings on it — and I took that, too.

When I returned to my school to teach, I excavated a dust-covered overhead projector from a supplies closet. I literally typed up Señora’s worksheets and transparencies one by one. I could have Googled resources on the subjunctive mood or passive voice, but transcribing Señora’s work felt like the right thing to do. I didn’t wholesale avoid technology; I just recognized where my priorities as a real human teaching real humans should lie — with them.

I started class with “¿Qué hay de nuevo?” sipping tea from Señora’s mug while taking mental notes about who was uncharacteristically quiet, who hadn’t slept, who wasn’t OK. And I followed up with those students after class in a way no bot ever could.

Becca Katz is an educator, mother, friend, partner, nature-lover, writer, activist, and edupreneur. She co-founded Good Natured Learning to grow educators’ capacity to integrate nature connections into their routine teaching practices. Becca writes Learning, by Nature, a Substack about all things nature.