Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

The operation starts before dawn and continues until late in the evening.

Volunteers pick up vulnerable Fridley Public Schools employees and make sure they make it to schools. These teams from Education Minnesota, the state teacher’s union, make sure everyone gets home safely too.

School leaders track unfamiliar vehicles and field calls from concerned families. One can’t make rent. Another is running low on food. They check in with the families of students who aren’t in school. Have they been detained by ICE?

Superintendent Dr. Brenda Lewis also has a new morning routine: She visits every school accompanied by security.

“People are always like, ‘Did you see ICE?’ We see ICE every day, right?” Lewis said, as Steve Monsrud, a district security official, drove her around the perimeter of school buildings on a recent February morning.

At each stop, she checked in briefly with the principal before moving to the next school.

She was looking for more than just suspicious vehicles. She was watching for immigration agents encroaching on school grounds or interfering with the school day. And she’s making sure they know that she’s watching.

“Our role isn’t to spot ICE,” she said. “Our role is to ensure that our children and staff and families are safe at school.”

Fridley Public Schools is a diverse, tight-knit community just north of Minneapolis. Its 2,700 students include significant numbers of Somali and Ecuadorian students. The district has long been a place where school means more than just education, where social workers help families with basic needs.

But Operation Metro Surge, in which the Department of Homeland Security flooded the Twin Cities area with some 3,000 immigration agents, has compelled this district to dramatically expand how it supports families.

In Fridley, the school district has become more than a collection of schools. It has become the first line of defense: a logistical support system, a crisis response team, and for many families, a rare point of stability.

For Lewis, the role of public schools has never felt more clear — or more strained.

Lewis recalled walking through a school building recently when a student stopped her and asked if she was the “ICE fighter.” With a bewildered smile, Lewis said she responded that her job is to keep students safe.

“We shouldn’t normalize this,” she said.

Students are learning at home, but it’s not like COVID

Lewis said immigration enforcement became the district’s business when it disrupted the basic promise of public education: that children can access school without fear.

Enforcement has always been inconsistent and unpredictable, Lewis said, but in recent weeks, it has crossed new lines.

Lewis described an incident in early February when ICE agents blocked off a roundabout near a Fridley school, interfering with dismissal. Children couldn’t cross safely, and agents intimidated crossing guards, she said. Agents yelled at the principal and followed a school board member who lives nearby. They also followed a mother as she left pickup.

The incident occurred the same day Fridley Public Schools, along with Duluth Public Schools and Education Minnesota, filed a lawsuit against the federal government seeking to restore “sensitive locations” protections that would bar immigration agents from operating within 1,000 feet of schools.

Days later, the Fridley Police Department informed Lewis that it would send patrols to school grounds. Lewis is hopeful their presence will deter federal agents.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment.

Lewis said she is “cautiously optimistic” that border czar Tom Homan’s promise to wind down Operation Metro Surge will give schools some relief.

Multiple school districts in the Twin Cities have created virtual learning programs for students whose families don’t want them to leave their home. Lewis said Fridley launched its program in just four days. The district has extended virtual learning through the end of February, with approximately 400 children signed up.

Some have compared the district’s shift to virtual learning to the COVID-19 pandemic, Lewis said, but this moment feels fundamentally different: “That was a virus. This is man-made.” The threat is more targeted and only directly affects certain students and families.

During the pandemic, Lewis said, everyone was home. “Now only some are, and they are afraid.”

For students with disabilities, the disruption can be even more difficult. Teachers and paraprofessionals are doing what they can within the limitations of virtual learning, but the kind of support that happens naturally in a classroom is harder to provide through a screen.

Students are also cycling in and out of school, and that instability creates its own challenges for learning and for district operations.

Lewis pointed to one student who was detained with their family and recently released. The student’s mother told her, “My son is so excited to come back.” But because the child had been out for more than 15 days, the district lost funding for that student.

District stepping up to help with groceries, rent

Multiple times a week, Danielle Thompson, Fridley’s director of student support services, delivers boxes of food and other necessities to families who are sheltering in place. In the beginning of January, she created an online form to track what families needed. Now her team is helping around 60 families.

The school pantry is overflowing. Staff shop directly for fresh ingredients. Thompson described using gift card donations to purchase specific items families request, even something as particular as fish tank conditioner.

Thompson’s official role is to oversee special education, food assistance, and other support services, but she said families’ needs have grown far beyond that. With parents afraid to go to work, rental assistance has become an urgent need. Thompson and her team spend full days coordinating financial assistance, gathering documentation, speaking with landlords, and triaging emergencies.

After work, her own children have asked her if they are going to go shopping for themselves or to help someone. She said she hopes, at least, that she’s providing an example for her kids.

When asked how long the district can continue operating like this, she said at some point, the money will run out.

She applauds her team, who are “working hours outside of their school day,” she said. “They are just going above and beyond, and they’re my people.”

Thompson looked out the window and began to cry.

“Every day just feels like, ‘OK, what am I doing? Am I actually helping?’” she said. “Last week there was a day, I just cried the whole day, because it was like, ‘How are we going to help everyone that needs help?’”

Community support can’t erase students’ burden

As dismissal time neared, Monsrud, the security officer, repeated his route, with neighbors waving as he passed by. His patrol has become part of their routine.

The route remained quiet at first. Then his phone rang.

A neighbor reported a suspicious-looking truck with out-of-state plates parked in front of a board member’s home. Steve turned down quiet suburban streets glazed with ice, scanning for vehicles that seemed out of place, checking in with other security officials at points along the way.

They could not locate the vehicle after its initial sighting.

Lewis described the aftermath of previous incidents, when the district put out calls and observers flooded in. Volunteers arrived to watch the entrances, standing nearby, bearing witness. She called it both “brutal and beautiful.”

It has been horrible, Lewis said, to feel like she needs to protect schools from a federal agency.

Amid this uncertainty, the normal activities that make up the school week continue.

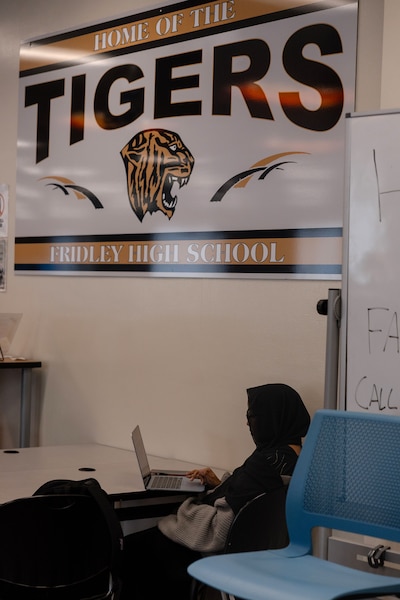

The next evening, the Fridley High School gym filled with noise. Sneakers squeaked, cheerleaders practiced their routines, and band members carried their instruments to the upper bleachers.

But the game was more sparsely attended than it normally would be. The students cheered loudly for the varsity girls basketball team, which was playing their rival Columbia Heights — another Twin Cities-area school district that has been heavily affected by Operation Metro Surge.

Fourteen-year-old Olga said she worries when her parents go to work because they are immigrants, even though they are here legally. Another student said they missed their friends and didn’t think any of this was fair.

The game ended with a win for Columbia Heights. The students didn’t linger, and the building quickly emptied.