Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

On a recent Tuesday morning, Mayor Brandon Johnson visited classrooms at Kelvyn Park High School in Hermosa to present certificates of recognition to teachers for Teacher Appreciation Week.

Flanked by an alderman and the chief of finance for the teachers union, Johnson posed for photos and created a scene rare to find before last year: The mayor standing side-by-side with teachers, some wearing bright red Chicago Teachers Union shirts.

The scene was an indicator of the pivotal role education has played in Johnson’s agenda in office.

When Johnson, a former middle school teacher and Chicago Teachers Union organizer, was elected last year, it was no surprise education would be a central priority.

The union catapulted Johnson into office, and his win was the result of a decade of CTU organizing against how previous mayors approached public education. Instead of a system in which schools compete for students and parents choose the best option no matter how far they may have to travel, Johnson promised to focus on bolstering neighborhood schools, many which have seen declining enrollment and fewer resources.

As Johnson hits the one-year mark in office, his appointed school board has overseen a change in the district’s funding formula and directed district leaders to come up with a new five-year strategic plan, to be voted on this summer, that would rethink the city’s school choice system, which includes charter, selective enrollment, and magnet schools that require applications for admission.

“We have to fund our schools based upon the need,” Johnson said in a February 2023 video interview with Block Club Chicago. “Every single school should have a social worker, counselor and nurse as the bare minimum.”

But Johnson faces a big challenge in carrying out his education agenda: Chicago Public Schools is facing a projected $391 million budget deficit next fiscal year and has provided little detail on how it will close the gap. Federal COVID money is running out and he must bargain a new contract with the teachers union.

Johnson’s agenda also called for free public transit for students, housing for the district’s 20,000 homeless students, and creating up to 200 more Sustainable Community Schools – a partnership with the CTU that provides wraparound services at needy schools. None of these promises have seen any progress.

Still, education may be the one area where Johnson has made progress during his first year in office, said Dick Simpson, professor emeritus of politics at University of Illinois at Chicago and a former alderman.

“In comparison to, say, his other problems — solving crime, for instance — he is much further along on the school agenda,” Simpson said.

The speed with which Johnson can deliver on his education promises is important because he will soon lose exclusive control over the Chicago Board of Education, as the school board begins to transition to a partially elected body this November.

In an interview with Chalkbeat, Johnson said his focus on education “has more to do with the urgency that families are calling for.”

“We’re talking about decades upon decades of school closures, the defunding of our schools, the attack on veteran educators, particularly Black educators,” Johnson said. “So our urgency is really centered around the needs of our young people and the needs that our families have.”

Bolstering neighborhood schools, but not without backlash

Johnson’s plans to bolster neighborhood schools kicked into gear last December.

Just before winter break, the board of education passed a resolution aimed at boosting neighborhood schools and rethinking Chicago’s school choice system, which encourages kids to enroll in public schools outside their attendance zones. Half of all elementary students go to schools that are not their zoned neighborhood schools and more than 70% of high schoolers do.

Johnson has described the choice system as a “Hunger Games scenario” that forces schools to compete for students and resources and results in less investment in neighborhood schools. The resolution said the choice system “reinforces, rather than disrupts, cycles of inequity” and must be replaced with “anti-racist processes and initiatives that eliminate all forms of racial oppression.”

Though many selective enrollment and magnet schools were created under court-ordered desegregation, many still lack the diversity of the city and are largely segregated by race and class. A couple dozen are integrated, but serve more white and Asian American students than the rest of the school district.

The board’s resolution did not change any current policies or suggest the closure of any schools. Board members emphasized that public feedback would drive any changes, such as to admissions policies. Board members have, however, said they plan to scrutinize charter schools more.

The resolution was praised by advocates who have long pushed for more investment in neighborhood schools and the Chicago Teachers Union.

Johnson “ran on equity,” said Stacy Davis Gates, president of the Chicago Teachers Union. “He said that our school district had to be more equitable, and the resolution that came from the Board of Education is speaking to the inequity and their efforts to ameliorate inequity that are often disproportionately experienced by neighborhood schools.”

But the resolution also sparked backlash from families whose children attend schools of choice, including those already frustrated that CPS was not providing bus service to general education students, largely those attending selective and magnet schools.

Those concerns pushed state lawmakers to file a bill that is up for a final vote this week, which would prevent the district from changing admissions policies for selective enrollment schools – something the current board signaled it may do. The bill would also prevent CPS from cutting funding for selective enrollment schools or closing any school until 2027, when the school board will be fully elected. The bill is supported by powerful state lawmakers and Gov. J. B. Pritzker.

Johnson said the bill would prevent the board from taking actions to help create “real equity” and would prevent the district from balancing its budget. He began rattling off the relatively small percentages of Black students at some of the city’s most sought after selective enrollment high schools and noted how those figures were higher about two decades ago.

“What I’m troubled by is that you have a school district that is hypersegregated and that stratification has continued to grow because you haven’t had leadership like mine directing the school board and the Chicago Public Schools to commit to real equity,” Johnson said. “So is Springfield intervening to protect segregation?”

Simpson noted that Johnson has “a more strained” relationship with the legislature and Pritzker, meaning he doesn’t have a lot of clout to fight for what he wants.

CPS changes funding formula

In March, CPS announced it would change how it distributes money to schools, delivering on another major promise Johnson made on the campaign trail to end student-based budgeting, which provides schools a set dollar amount for every child enrolled.

The new funding formula will now give every school a base level of staff and discretionary money based on need, which principals can use flexibly. This “needs-based” formula is meant to break a cycle in which underenrolled schools in underinvested neighborhoods lose money because they’re losing students.

That change, too, has drawn a fresh batch of concerns.

Parent leaders at selective enrollment and magnet schools said their budgets provide for fewer staffers next year under the new formula. Some Local School Councils are voting against their budgets for next year.

CPS officials have said that overall funding to schools remains the same as last year but individual schools could see changes. The district is looking for cuts at the central office to address the $391 million deficit, CPS CEO Pedro Martinez has said. CPS has not yet released school budgets for next year to the public.

The union also raised concerns about the formula, saying it lacks guaranteed positions, such as teacher assistants, and said some neighborhood schools have also seen cuts. Davis Gates blamed Martinez – not the mayor – for those flaws, because she said he is not explaining the changes well to the public or lobbying the state legislature hard enough for more money to prevent staffing cuts to some schools.

Sylvia Barragan, a spokesperson for Chicago Public Schools, said “multiple staff members” have visited Springfield throughout the session to advocate for more funding, and Martinez has pushed for more funding “for well over two years in Springfield, at our Board of Education meetings and beyond.”

CPS officials have said that no type of school is being disproportionately impacted. But Martinez has acknowledged that they are working to fix concerns at individual schools.

Mayor inconsistent on police out of schools

Some education-focused organizations have criticized the mayor’s administration for pushing big changes through or flip-flopping on commitments without properly engaging the public.

Hal Woods, director of policy and advocacy for Kids First Chicago, shared some examples. For one, the board publicly posted its resolution stating its intent to rethink school choice two days before the board voted, leaving little time for the public to digest it, Woods said. The district is currently holding hearings to collect feedback for the next strategic plan.

Parents and schools have also demanded more information about why the district is changing its funding formula, Woods said. He added that the former formula wasn’t working for many schools, but the district hasn’t shared enough about the new formula or its impact on schools.

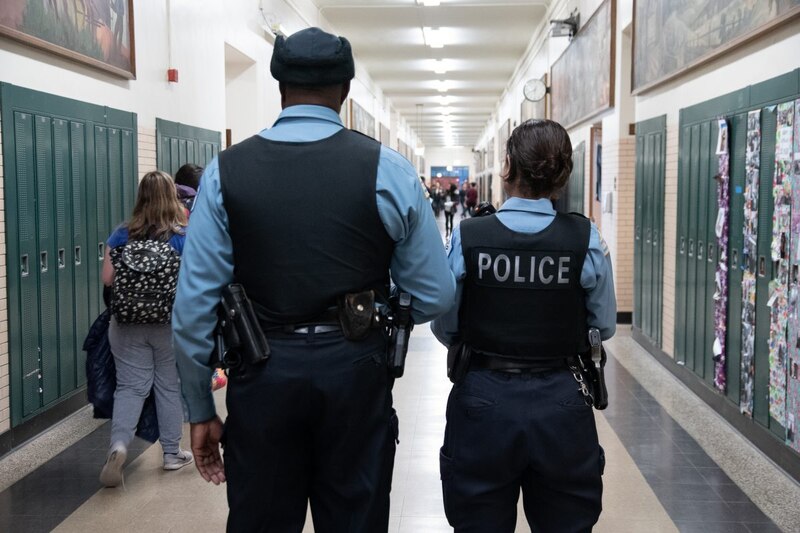

Woods also said the mayor could be more clear with communities on his position to remove police from schools. Johnson supported getting rid of campus police on the campaign trail but later said local schools should have the power to choose whether to have school resource officers. Then in February, the mayor backed the school board when it voted to unilaterally remove officers from all campuses by next school year.

“There’s plenty of data that shows how police in schools impact youth mental health, right, and the disproportionate impact on Black students and Latino students, but … they’re kind of making a decision based on their values without kind of educating the public on why they’re making that decision,” Woods said.

Johnson said “he will talk to anyone” and rejected the idea that his administration isn’t transparent enough. He pointed to the handful of board of education meetings that have been held at high schools in the evening instead of downtown during the day. He believes some of that criticism comes from people who “have had unfettered access” to previous mayors, and there are “people who now have access who were shut out before.”

“I’ve said all along,” Johnson said, “there’s plenty of room at the table for everyone.”

Fulfilling other promises before school board shifts

There are several promises Johnson hasn’t made progress on, including expanding Sustainable Community Schools, a CPS partnership with the teachers union that pairs needy schools with community organizations that provide wraparound services to families. Each program costs about $500,000.

While Johnson has shifted focus toward neighborhood schools, his administration is struggling to support the 8,900 migrant students and families who have arrived in Chicago from the southern border since at least August 2022.

As a candidate, Johnson promised to invest more money in bilingual education. Between August 2022 and last August – five months after he was elected – the number of bilingual-certified educators grew by 90, according to CPS. Between last August and the end of April, that figure grew by another 106 teachers.

CPS and the city also opened a welcome center to help migrant students enroll in school and access other resources. CPS said it helps direct families to schools with the proper resources when they are struggling with enrollment.

Still, the union, lawmakers, and families have reported that many schools are struggling to meet the needs of migrant children, most of whom are learning English as a new language and are homeless. Those challenges include lacking enough staff to help children with specialized English instructions.

Johnson again blamed state lawmakers for their efforts to protect selective enrollment schools, saying it would “prevent us from having the type of budget, autonomy, and flexibility to invest in those schools” that lack resources to help English learners.

Johnson also hasn’t gained ground on providing the district’s 20,000 homeless students with housing — a bold promise tied to a signature campaign promise to pass the Bring Chicago Home referendum. That ballot measure, which would have used a tax on property sales over $1 million to help fund housing for homeless families, failed in March.

Ultimately, Johnson’s education legacy and the fate of his preferred policies will depend on what the future elected school board does, Simpson said.

“I do think the new school board, as it begins to take shape, will revisit these issues and either move forward with the general direction of Johnson and the current school board, or will roll them back to an extent,” he said.

It could also depend on the ongoing financial challenges for Chicago Public Schools. Asked how he will achieve his goals in the absence of more money from Springfield, Johnson said he’s exploring other “measures and steps that we can take as a city.” When pressed for details, Johnson’s office declined to elaborate.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.