President Obama’s recent call for less standardized testing spurred lots of national chatter, but many of his specific proposals involve steps Colorado already has taken.

For example, the “testing action plan” released Saturday by the U.S. Department of Education recommends that states cap the percentage of instructional time students spend taking required statewide standardized assessments so children spend no more than 2 percent of their classroom time taking the tests.

In Colorado, 2 percent of classroom time is about 21 hours in a school year, said Department of Education spokeswoman Dana Smith.

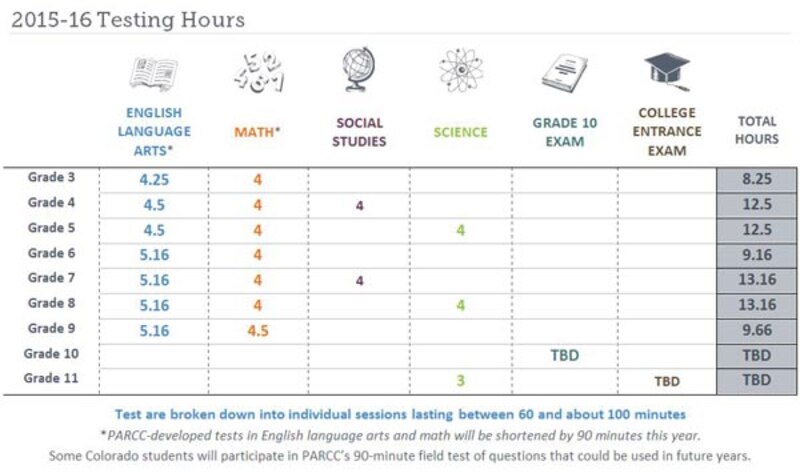

But the statewide CMAS tests will consume only a low of 8.25 hours in third grade to a high of about 13 hours in seventh and eighth grades next spring, according to CDE. The time needed for college-readiness tests in 10th and 11th grades isn’t known because those exams haven’t been chosen. (See graphic at the bottom of this article for details.)

The federal action plan also says, “Low-quality test preparation strategies must be eliminated” and calls on districts to take concrete steps to “to discourage and limit the amount of test preparation activities.”

Colorado testing critics have complained about the overall burden of testing, including preparation for state tests and tests chosen and given locally. But the state has no requirements for control over test prep or local testing.

Similarly, the action plan’s recommendations for flexibility in use of test scores for educator evaluation mirror things Colorado already is doing, said Katy Anthes, the state education department’s interim associate commissioner.

“The Administration has adjusted its policies to provide greater flexibility to states in determining how much weight to ascribe to statewide standardized test results in educator evaluation systems” and will work to help states use such flexibility, the plan states.

“There’s nothing in here that’s not already built into our system,” Anthes said.

Colorado law requires that 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation be based on students’ academic growth. But districts can – and do – use other measures in addition to growth based on multiple years of state test results.

During the 2014-15 school year, districts could choose to not use growth measures or to use less than 50 percent. And a testing law passed last spring bars the use of data from state tests for evaluation in the current 2015-16 school year.

The testing action plan acknowledges the role of the Obama administration in the growth of testing but says assessment problems are the “unintended effects of policies that have aimed to provide more useful information.”

Along with calling for such high-level goals as quality tests, assessments aligned to what students are learning in class and the linking of tests to improved learning, the document also promises federal financial support for states to improve and streamline testing programs.

And the action plan draws a bright line in calling for the continuation of annual statewide tests, a requirement some testing critics would like to eliminate.

Changes in Colorado’s testing system have been driven both by cutbacks required by a 2015 law and by time reductions made by PARCC, the consortium that provides the language arts and math tests currently used by the state.

But those changes aren’t likely to dampen legislative interest in testing, which was the top education issue during last spring’s legislative session.

“Until we have an assessment tool that parents trust, I’m confident that we will continue to see high opt-out ratios and annual legislation to withdraw from PARCC,” said Parker Republican Sen. Chris Holbert, a member of the Senate Education Committee.

Learn more about the Colorado testing system in this archive of Chalkbeat Colorado stories.