A broad coalition of education reform and civil rights groups is lobbying against a proposed change to the way Colorado rates its schools, arguing that it would fail to provide a complete picture of how schools are educating the state’s most at-risk students.

State Department of Education officials say that few schools’ ratings would change as a result, and that the new system would better gauge how smaller schools are doing.

The State Board of Education is set to vote this week on the revision to the rating system, known as the School Performance Framework.

But it’s uncertain whether the move would be accepted by the federal government. As it stands, proposed guidelines for the nation’s new K-12 education law — the Every Student Succeeds Act — would prohibit it.

The proposal is one of several changes to the state’s accountability system the state board is scheduled to consider this week. Schools that fall at the bottom of the state’s rating system for more than five years face sanctions such as being handed over to a charter school or being shut down. The system has been on pause for a year because of a switch in state assessments.

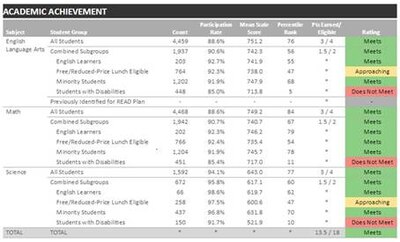

Under the current system, schools are rated based on students’ state test scores and other measures, including graduation rates in the case of high schools.

Schools get points based on the performance of all students, and also on the scores of students in each of five categories of historically underserved populations, such as English language learners, students with individualized lesson plans and those living in poverty.

School districts have complained that the current system penalizes schools with large populations of students that fall under multiple categories, known as subgroups.

“It’s an imbalance and it’s not a fair appraisal,” said Scott Graham, executive director of student academic support for Weld District Re-8. “… Is it fair to count students three or four times?”

In a letter to the State Board of Education supporting the change, Graham and other Weld officials say more than one-third of Fort Lupton students are counted three times.

Education department staff are recommending that schools earn points based on the scores of all students, and then all five subgroups lumped together. State officials say the result will be a more streamlined system that will be more understandable to parents, teachers and others.

But in a May letter to the state board, a coalition of 22 education reform advocacy and civil rights groups argued the change “would have significant implications for educational equity.”

One argument in the letter is that schools receive funding to meet the needs of subgroups, such as federal Title I funds for the state’s poorest students.

“As of right now, there are dedicated funding streams for educating each of those kids,” said Ross Izard, senior education policy analyst for the libertarian Independence Institute, which is part of the coalition. “As long as we’re funding special needs programs, each of those programs need to produce results and each one needs to be accountable to taxpayers.”

Another signee, the Colorado Children’s Campaign, analyzed state data and predicted results for about 30 of the state’s more than 1,800 schools would be inflated as a result of the proposed change, said Leslie Colwell, the nonprofit’s vice president of education initiatives.

“When you lump all of these groups together, it sends a message that all these kids have the same needs — and that’s not true,” Colwell said.

The districts that got a bump under the advocacy group’s analysis ran the gamut in terms of how they have scored historically on the state system, she said.

The proposed change has begun to attract national attention. On Monday, a Washington D.C.-based civil rights organization, The Leadership Conference, called it a “sleight of hand.”

“You can’t fix a problem that you don’t identify,” Wade Henderson, the conference’s CEO, said in a news release. “Coloradans deserve to know how all students are doing and to expect that the state will use that information to make smart policy decisions about how to help struggling students.”

Graham said the needs of students from historically underrepresented groups would be met under the change. As part of the proposal, reports on each school will still include data on each student subgroup; but when it comes to assigning scores, all those groups will be counted as one.

“Teachers will be able to work with the same data they’ve always had,” he said.

Schools also would be responsible for addressing how they plan to improve instruction for any subgroup of students that does not meet state expectations.

State education department officials point to another upside to the proposed change: a far fuller picture of how small rural schools serve students from underserved populations.

Under the current system, schools are not judged on how they do with a subgroup with fewer than 16 students — the threshold the state uses to protect student privacy. Putting all the subgroups in one large group means those districts will be held into account for those results.

Several states, including Mississippi and Michigan, have taken a similar approach to school ratings under flexibility previously granted by the U.S. Department of Education.

However, proposed guidelines released in-late May state clearly that such ratings would be unacceptable under the new Every Student Succeeds Act, or ESSA.

Alyssa Pearson, interim associate commissioner for Accountability/Performance at the Colorado Department of Education, said the department is taking a wait-and-see approach with ESSA regulations.

Pearson added that the state will need to make even more changes to its accountability system by 2017, when ESSA goes into effect.

“This will be an ongoing conversation,” she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly named the new federal law, the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Update: This post has been updated to include an image of the proposed school performance framework. This post has also been updated to more accurately reflect Ross Izard’s comments.