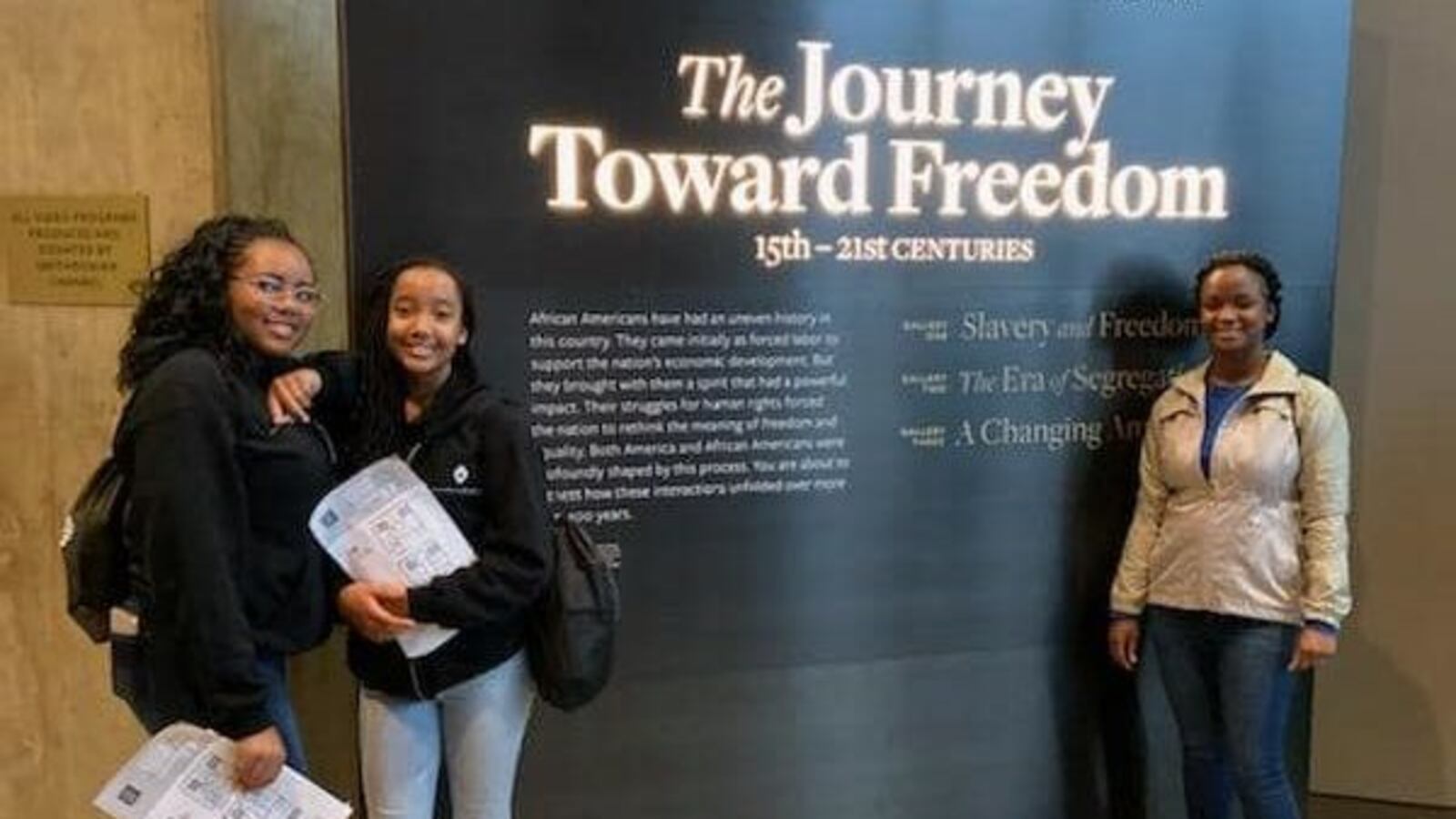

Inspired by what they learned and frustrated they hadn’t been taught it in school, Denver students who visited the national African American history museum last fall are pushing the school district to include more black history in its U.S. history curriculum.

“After experiencing the D.C. trip, I can now say it’s unacceptable for any black student to have to travel over 1,000 miles away in order to be enlightened in the way that I have,” said Kaliah Yizer, a freshman at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Early College in far northeast Denver.

“Growing up, my grandma always reminded me that closed mouths don’t get fed,” freshman Dahni Austin told the district’s school board last week. “We want to learn more about other African Americans who have made a change or stood up for what they believe in.”

It’s wrong, students said, that the black history taught in schools is centered around oppression, with minimal attention paid to the contributions and strength of African Americans. Junior Alana Mitchell said it’s sad she knew Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492, but didn’t know until going to the museum how young Martin Luther King, Jr. was when he died.

“It’s unfair that hundreds of schools in Denver provide the kids of white descent with every inch and minute of their history, but we have almost no recollection of black history,” said sophomore Savoy Proctor. “Please help us become stronger as a unit and wiser as individual kings and queens.”

Denver Public Schools officials were quick to agree. This latest criticism comes on the heels of similar concerns about the way the middle school curriculum treats Native American history.

“The one thing that motivates me to be up here is to be sure students are seen and heard,” said school board Vice President Jennifer Bacon, who has pushed the district to improve education for its 12,000 black students. “We will partner together to fix our curriculum.”

Some changes are already underway, sparked by a recent district audit of high school history curriculum that found it lacking in diverse narratives, said Tamara Acevedo, deputy superintendent of academics. And she promised that there are more to come.

The teachers at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Early College aren’t waiting. They testified that they’re already making major changes to their history curriculum, adding units on the cultural and political history of Africa, American slave rebellions, Marcus Garvey, Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, and Hurricane Katrina’s impact on communities of color, to name a few.

“Our students, as you’ve heard, asked for change,” ninth-grade geography teacher Lindsey Kartchner said. “Our idea of what was good enough in teaching black history was not.”

But black history, the students said, should not be “supplemental” — an add-on to a curriculum that has long focused on white stories. Acevedo said the district doesn’t see it that way.

“The work we’re doing to put in texts and resources that do tell a more complete story and a story that’s important, we don’t see that as supplemental,” she said. “It’s a required part of the curriculum,” and she said the district is coming up with new language to make that clear.

Still, the students and educators at Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Early College are pushing for the type of fundamental change that will make such advocacy unnecessary in the future.

“You cannot teach American history without teaching African American history,” said senior Zyeria Turner-Johnson, whose yearn for knowledge about her past helped inspire the trip to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in October.

“I saw how much my ancestors fought for me to be where I am today and I’m going to continue the fight,” junior Jenelle Nangah, who went on the trip, told the school board last week. “Now my question for you is: Are you fighting with or against us?”