A 12-year-old girl set her alarm clock for 6:30 a.m., as if she were going to school.

A bleary-eyed college student blinked awake, thinking about yesterday’s test and hoping that multiple internet outages didn’t stop it from going through.

A school counselor donned a face mask and gloves to pass hundreds of lunches through car windows.

A stressed-out parent sat alone with her 8-year-old son’s math assignment. Her son had taken refuge behind the couch, frustrated he couldn’t figure out the problem.

In Colorado and around the nation, K-12 schools and universities began to close in mid-March and will remain closed at least through the end of the school year.

College students returned home. Teachers at every level tried to pivot to online instruction. Districts scrambled to provide laptops and hotspots and set up meal distribution sites. Schools planned online proms and delayed graduations. Parents found themselves thrust into new roles.

Many child care centers, meanwhile, remained open, with air high fives replacing cuddles.

As a heavy spring snow blanketed the state, journalists from news organizations across Colorado set out to chronicle one day in the life of the state’s residents during this extraordinary time.

The stories from April 16 that we’ve collected here present a snapshot of education in the time of coronavirus. School closures have been a key part of the social distancing strategy deployed to slow the spread of coronavirus, and it’s not clear when — if ever — the old normal will return.

Pete the Cat and air high fives: Caring for young children in a coronavirus world

Dressed in purple scrub pants and a coordinated print top, Catherine Scott started her work day with a spray bottle of bleach solution, wiping down door handles, tables and a laptop keyboard.

Scott is not a health care worker, but a preschool teacher — often tasked with opening the child care center where she works in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood.

When children began arriving at Venture for Success Preparatory Learning Center with their parents, Scott met them at the front door, thermometer in hand. After temperature checks, parents logged their child’s arrival on the laptop, and everybody washed their hands in the sink up front.

Scott, who the youngsters call “Miss Cathy” or “Miss Cappy,” had just three children in her classroom — a 2-, 3-, and 4-year-old — two of them new to the center. It was a far cry from the usual 15 she would have on a day without coronavirus.

After many child care providers closed last month, state officials made a recommendation that caught some by surprise: Stay open, with precautions, to care for the children of working parents.

Scott and her co-teacher recorded morning “circle time” so the video could be posted to a private YouTube channel for children whose parents kept them home. They sang their good morning song in English and Spanish and read the book “Pete the Cat and his Four Groovy Buttons.”

One of the biggest challenges of preschool in the coronavirus era is social distancing. Instead of the usual snuggles and hugs, Scott has switched to distance hugs, air high fives, and pats on the back. One student spontaneously jumped into her lap, then quickly realized her mistake.

“I sorry,” the girl said. “Air high five.”

— Ann Schimke, Chalkbeat

Maintaining a routine, in hopes that one day things will be normal again

The 12-year-old girl still sets her alarm for 6:30 a.m. to get ready for school even though class is now in her home’s kitchen.

Most of Elizabeth Vitela’s family, including three other kids, are up later.

The younger ones, 3 and 10, are getting restless, Vitela said. The 10-year-old boy’s attitude was on display that morning.

Just after 9 a.m., he ran into a problem on a math assignment. After he picked a shape and wrote about five of the shape’s characteristics, the online system wouldn’t accept his answers.

Mom suggested he go back to look at the instructions. Just once.

Her next step: “I said ‘OK, we’ll do it your way,” Vitela said. “If I insisted it would have been a big argument.”

At 10 a.m. when the boy had a video call with his teacher and his class, he asked for help. They identified the problem: The program only wanted him to enter three characteristics of the shape — not five.

In the afternoon, Vitela had a video call with her 3-year-old daughter’s preschool class. The teacher gets four preschoolers on a call to read them a story, and ask questions.

But Vitela’s daughter wasn’t interested.

“I had her sitting still and she didn’t like that,” Vitela said. “Finally when the teacher had them looking for shapes and things around the house, she was happy doing that.”

Usually the teacher assigns reading or some work after the call. Some parents in the Adams 14 district were having trouble with the platform, so the teacher cancelled the assignment. Instead she promised to record her reading sessions with questions and pauses so parents could play them for their kids whenever they show more interest.

Vitela still puts her children to bed about 8 p.m., “so they keep their routine for when they go back to school,” she said.

Despite the challenges, Vitela is happy to spend more time with her kids.

“I like having them home,” Vitela said. “I’m glad to be able to help them here.”

— Yesenia Robles, Chalkbeat

COVID Diaries

Feeding mind and body, with grab-and-go meals

The vehicles pulled into the parking lot on the west side of the school.

Michelle Cunningham was there, at Avery Parsons Elementary School in Buena Vista, in a surgical mask and gloves, greeting parents and students by name and giving them thumbs-up signs and smiles in lieu of high-fives and hugs.

The school counselor has been struck by the volume of families showing up for free meals. Though nearly one-third of the school district’s roughly 1,100 students are eligible for government-subsidized lunches, a measure of poverty, only about 40 children a day typically take advantage, she said. Now the district is handing out 400 meals a day, she said.

“As counselors, we know brains work best when physiological needs are met,” Cunningham said. “Its benefits go beyond food. I’m out where I connect with families. We give them a warm smile, a ‘How are things going?’... It’s a highlight of the kids’ day — a daily field trip to go get your lunch! This check-in connection can make it easier for them to ask for help.”

In communities across the country, school buildings closed for learning remain open for meal distribution, extending a social safety net during the crisis. That holds true in Buena Vista, a tourism-dependent community set amid the majestic Collegiate Peaks.

With retailers, restaurants, and other small businesses closed, hundreds of families are out of work. Many just received their last paychecks. The virus caused the cancellation of a summer whitewater festival in nearby Salida, part of a $75 million rafting season for the local economy.

Even so, Cunningham said she is proud of how the community has rallied.

“The school board, the business owners, the community leaders, the churches, the school’s lunch ladies … Everyone is stepping up in so many ways to support each other.”

— Jan Wondra, Ark Valley Voice

Fighting bad internet to finish college from his parents’ home

Rashib Basnet woke with slightly bloodshot eyes at about 8 a.m. to the sound of his parents talking on the phone downstairs. Those daily phone calls, the 21-year-old said, can be a sometimes unwelcome early-morning alarm for a groggy college student accustomed to sleeping in.

The first thing that came to Basnet’s mind as he began to think about his day was a test that he took the day before. “My Wi-Fi died a couple times, so I hope that my test went through,” he said.

Basnet returned home last month to Colorado after the novel coronavirus upended his senior year at the University of Washington in Seattle. His experience is representative of college students across the country and state who must now finish school in new and unfamiliar ways.

“I just don’t associate staring at a screen with a PowerPoint while sitting in my bedroom as, like, an actual class environment,” Basnet said.

Basnet’s new homebound college experience comes with a daily 9 a.m. exercise routine where Basnet works out in the basement of his parents’ Centennial home with a single 20-pound weight and tattered resistance bands. He cursed at his unreliable, worn-down treadmill, which only allowed him to run about 10 minutes and decided to jump rope instead.

He settled into his first class at 11 a.m., praying that his internet wouldn’t cut out.

Basnet, an aspiring pediatrician whose days are also filled with studying for the MCAT, had a busy schedule for the day, including a Zoom lecture about COVID-19 in his infectious diseases and the environment class.

The daily shifts from coronavirus are difficult for many reasons, he said. It’s hard to finish out your senior year without the prospect of a formal graduation. And there are logistical and mental hurdles to overcome.

“You find yourself not focusing as much as you would in an actual class,” Basnet said.

There are positives, though.

He feels fortunate to spend more time with family members, who aren’t able to work during this time. He’s learned that his resolve to further his education is stronger than ever. And someday he hopes he’ll be able to help others if another pandemic occurs.

But next time, Basnet said, he’d opt for more reliable Wi-Fi.

— Jason Gonzales, Chalkbeat

Remote learning blurs lines between home and work. Fun Fridays are a silver lining

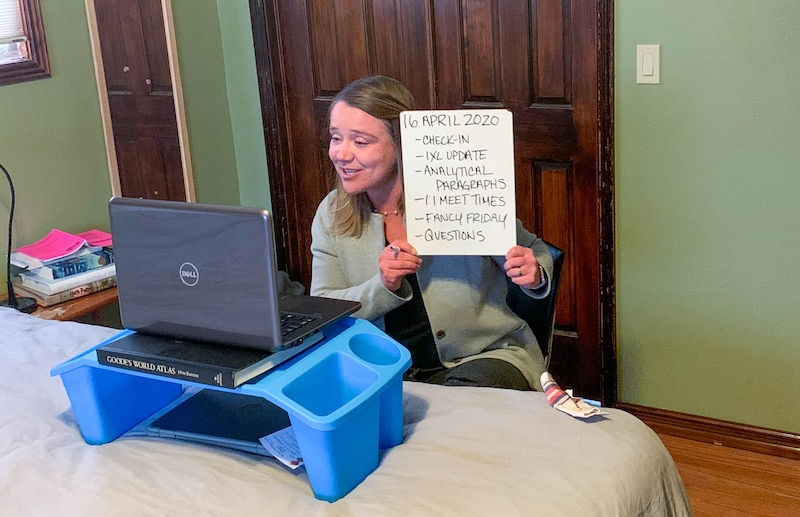

“Everything is different. There was no preparing for this, even though I thought I was prepared,” said Robin Fritsch, an eighth-grade teacher in Buena Vista, who, like teachers around Colorado, has made the shift to online learning. “From having my students in school to having to structure a way to create those authentic learning encounters at home, while maintaining my connections with 82 students.”

Fritsch’s husband is also a teacher. They’ve both had to adjust to teaching from home and handling the education of their own small children. They juggle schedules; who is online interacting with students, who has conference calls.

Fritsch started her day with phone conferences with parents, then connected with students via emails and prepped low-tech versions of lessons, before getting on a video conference to begin online lessons.

The line between home and school “has vanished,” she said. And she deeply misses the physical connection she used to have with students.

“I’ve spent the whole year building relationships with these students. Not seeing them every day, not being able to have the personal relationship to keep them moving forward is absolutely painful – it is crushing.”

The digital divide is a major challenge. She worries not just about students with no internet access, but those with unreliable broadband in the far reaches of her rural district.

“At Ranch of the Rockies, if there’s a gentle breeze, the internet goes out,” she said.

But the internet has also let her into her students’ homes, especially on Fun Fridays.

“Last week it was bring your pet to class,” she said. “I met pigs, lizards, birds. Tomorrow (Friday) is Fancy Friday. We’ll get dressed up as if we’re going to a fancy party — of course, it’s mountain formal.’”

— Jan Wondra, Ark Valley Voice

‘He’s hiding behind the couch right now’: Remote learning can be a struggle

Natalie Perez woke up at 6:30 a.m. to the sound of her husband’s alarm nudging him to get up for work at their family’s Mexican restaurant. Before the coronavirus, Perez would go too. But now she spends the weekdays at home with their 8-year-old son.

Perez lay in bed in her southwest Denver home. These days, she often finds it hard to get up. She fell back asleep until 8:45, when her son Roman was set to check in with his third-grade teacher by phone.

After the call, mother and son debuted the family’s new waffle maker. The waffles they made were huge and fluffy, topped with strawberries and Lechera, a sweetened condensed milk.

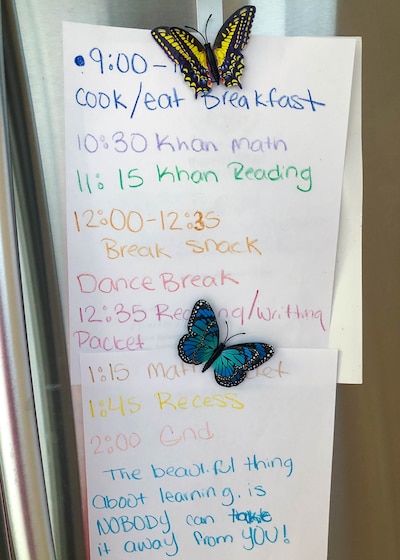

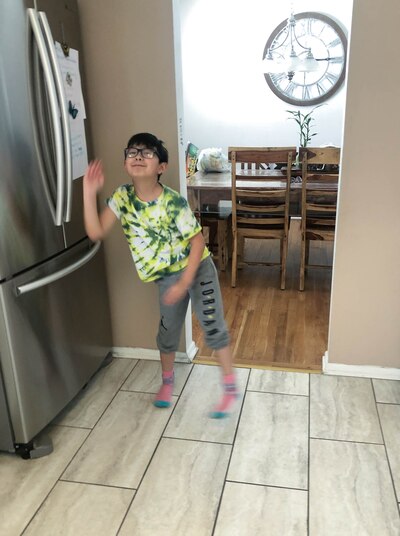

Roman started his online schoolwork at 10:30. Perez cleaned the house and showered, then fed Roman a snack of orange slices. He took a dance break, grooving in his stocking feet to a cover of the ’90s hit “I Like to Move It” from the movie “Madagascar.”

Next up was math. It was going well until the last part: a word problem that asked Roman to convert 50 kilometers into half meters. Perez didn’t understand it either, and Roman got frustrated. “He’s hiding behind the couch right now,” Perez said. “This is every day.”

They moved on to reading and writing, finishing around 3:30. Roman spent the late afternoon watching a fantasy show called “Trollhunters” while Perez took a nap.

Not being busy has been difficult on her. At first, she was nervous about her family getting sick — especially Roman, who has breathing problems. But lately, she’s also found good in the situation. It’s brought her closer to her dad, and she cherishes the time with her son.

Before, she said, “I was always in a rush. I felt like I couldn’t really enjoy things.”

Now, “there’s no rush for anything.”

Around 7 p.m., Perez cooked hot dogs for dinner. At 8, the family stood outside and howled in solidarity with front-line coronavirus workers. Usually, they hear neighbors howling too.

But on this snowy night, they were the only ones.

— Melanie Asmar, Chalkbeat

This story is powered by COLab, the Colorado News Collaborative. Chalkbeat and the Ark Valley Voice joined this historic collaboration with more than 20 other newsrooms across Colorado to better serve the public.

More stories from the project

Click on the map to find more articles