Brianna and her friends were all smiles in the car, soaking in their high school football team’s win. The 14-year-old replayed the joys of the day in her head: the corny jokes, prank calls, improvised dance routines.

Then she was jolted by the sound of a loud pop. A man with a rifle was shooting at someone in the street. The smell of smoke filled the air as the onslaught of bullets blasted through the car, leaving Brianna with bullet fragments lodged in her forearms.

Soaked in blood and covered in broken shards of glass, she was rushed to the hospital, where she spent the night surrounded by a chaotic swarm of adults trying to figure out what happened. She has never forgotten that night.

“I could have been gone,” she remembered.

Many of Detroit’s young people have dealt with trauma — from crime, poverty, abuse, environmental issues, and currently with the coronavirus pandemic. It’s a reality that causes immeasurable disruptions in learning. Often, teachers don’t have the necessary training to provide support, and if students don’t have a trusted peer or adult they can confide in, they are left on their own to deal with the impact.

Brianna, a senior, is among a group of teens helping the city’s youth combat trauma. The students, all enrolled at Detroit Collegiate High School, a charter school on the city’s east side, created Detroit Heals Detroit. This group brings together young people from across the city for periodic healing circles that help them process their trauma through discussions, writing, and group activities. They’ve also published a collection of student reflections.

The healing circles, held on Saturday afternoons on the second floor of the Chandler Park Library in Detroit, are usually focused on the everyday traumas students experience.

But none of them could have anticipated the trauma that has come as they cope with a pandemic that has closed their school buildings, and left them with a growing uncertainty about the future.

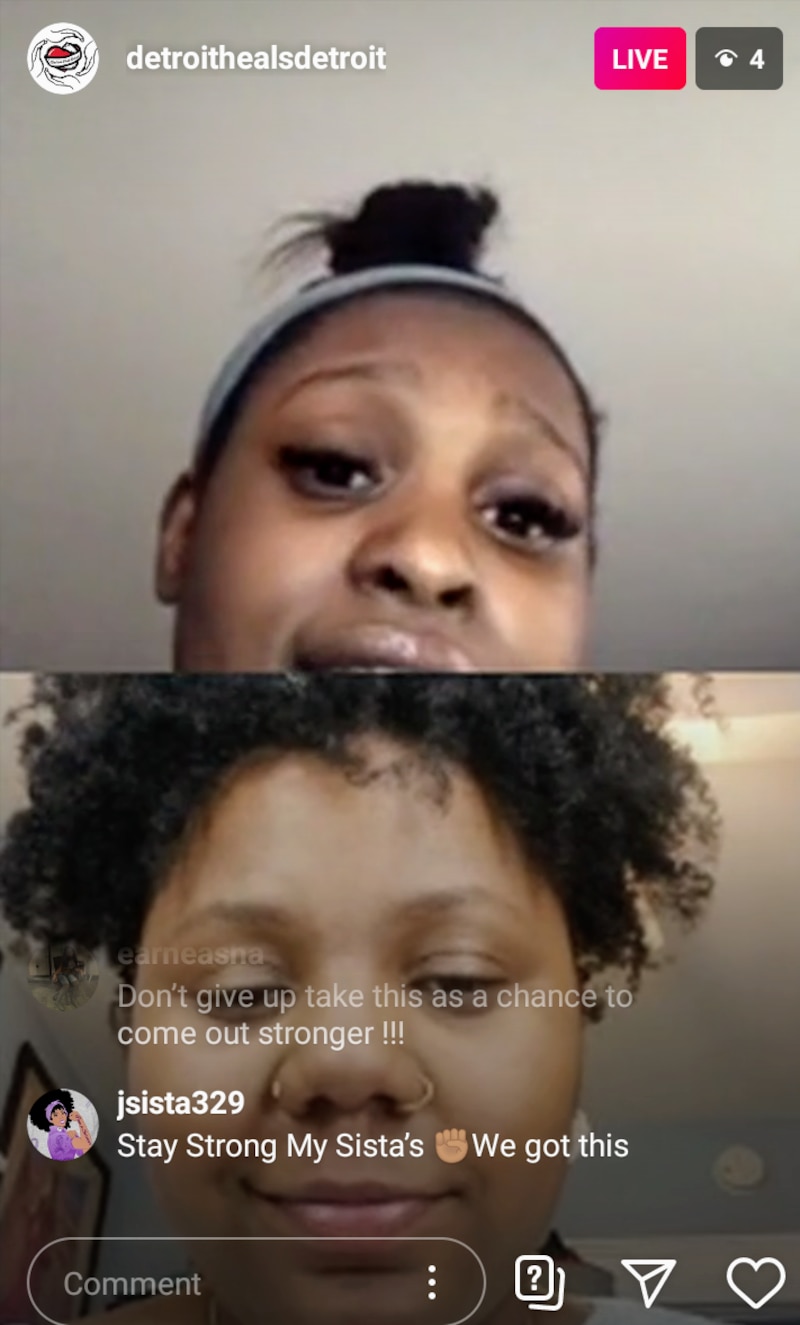

That’s why they held an impromptu, virtual healing circle on Instagram Live recently, giving each other a chance to come together while confined to their homes. Brianna and junior Earneasha Byars moderated the discussion, giving their peers a chance to share their feelings and mourn the lost school year.

“Being in the house is depressing for one. Not being able to go to school is upsetting because this was our most important year,” Earneasha said. “It stopped our daily lives. It’s like we’re on a break from reality. No education. No money. No nothing.”

🔗The consequences of trauma

The pandemic has halted the face-to-face healing circles. But it hasn’t stopped these students from putting the lessons they’ve learned into action.

The conversations they’ve had since this group formed has allowed them to talk openly and honestly about their pain, without fear of being judged.

“You may not even know it because even the smallest thing can really hurt you. And it made me more in touch with my feelings, being able to actually say when something hurts me,” Brianna said.

Someone who experiences trauma — an emotional response to a harrowing event — may have experienced violence, abuse, neglect, family dysfunction, death, poverty or even racism. It is an unrelenting hurt. If left unaddressed, bad grades, missed school days, or dropping out of classes altogether can result. A person may feel hopeless and powerless, or perceive the world only as a source of danger.

Brianna, now 18, was terrified of leaving the house. Even though the shooting incident happened four years ago, random, loud noises still disturb her.

For many of Detroit’s young people, the long-term effects of trauma can provoke a series of lifelong problems: depression, substance abuse, or entering the criminal justice system. In a Detroit district survey, a significant number of students said they felt unsafe at school, contemplated suicide or felt depressed during the school year. These feelings are often the result of one or more traumatic experiences.

Trauma is felt across the state — and nation — and impacts not only children, but also adults. In 2016, the state health department surveyed thousands of Michigan adults about their childhood experiences and found 39% of respondents reported being verbally abused, 29% reported substance abuse in the household, and 18% reported physical abuse. One out of five respondents reported experiencing four or more traumatic experiences.

One study found that even though traumatic experiences are prevalent across income and education levels in the nation, youth of color, those from low-income backgrounds, and LGBTQ youth are significantly more likely to face these types of adversities and experience trauma as a result.

Yet students shouldn’t be seen as “broken” or victims of their circumstances, said Dr. Roland Coloma, an assistant dean of education at Wayne State University and co-director of the Kaplan Center for Research on Urban Education. Students should be taught how to build upon the resilience in themselves.

🔗Learning to heal, together

By showing vulnerability, Brianna helped build resilience. After the shooting, she needed to be closer to her family and friends. They helped her, and she now feels a deep sense of purpose to support people who suffered the way she has.

At Detroit Collegiate, Principal Michille Roper-Few is working to make the school more “trauma-informed” by creating a culture of sensitivity, awareness, and understanding.

Roper-Few said she’s been impressed with the students’ selflessness and how they model good behavior for their classmates. They’re quick to try to diffuse verbal confrontations between their peers and will alert the teachers when something bad is happening or will happen.

“They’re a great group of kids. They always have been,” she said. “They’ve been through a lot. They’re trying to give back to others while also finding their way.”

Those close friendships have been important to keeping senior Silyce Lee on a positive track.

“I never had that. There’s somebody out there that cares about you,” he said. “I have family but the support is, like, low. We all love each other but everybody’s busy.”

Sirrita Darby, director of Detroit Heals Detroit, started conducting healing circles when she was a teacher at Detroit Collegiate because she saw a need. At first, students were shocked to see their teacher show so much honesty and vulnerability about her own childhood trauma. The experience helped eliminate the gulf between them.

“We’re like, ‘Oh, I feel comfortable talking to her. I feel like I can tell her my story,’ ” Earneasha said. “She’s not going to judge me.”

When it came to writing about their trauma, Darby encouraged students to let the emotions flow without worrying about spelling, grammar, and other rules typical of writing assignments. This freedom actually helped her write better, Brianna said.

“Sometimes that can be hard for students because they feel like they’re judged because they can’t write as well as others. They can’t put their thoughts into a paper,” she said.

Darby no longer teaches at Detroit Collegiate. But her work at Detroit Heals Detroit focuses on empowering youth to imagine hope and possibility for themselves while also researching the root causes of trauma.

Being a part of the conversations has contributed to her own healing as well, Darby said.

Silyce, Earneasha, Brianna and other members of Detroit Heals Detroit are now a tight knit clique. They still live with trauma, but they survived and are now moving forward.

Earneasha, for instance, has lived with the constant threat of gangs and the fear that one day, her mother will get an unbearable phone call saying she has to bury her daughter. But Earneasha is still tough-minded.

Silyce is still mourning the loss of a family member who died in a car accident. His cousin was the sun to him, and he misses her warmth and kindness. Despite the grief, Silyce loves making people smile.

Brianna is witty, gentle-hearted and perceptive. Even though the memory of the shooting still lives with her, she continues to put the pieces of her life back together and now feels whole again. The memory, she said, has helped her cultivate empathy for others, especially students like her. She doesn’t want them to be afraid for the rest of their lives.

“I stayed in the house for so long and until recently I just decided okay, yeah, I’m gonna go … I’ll go to this party,” she said in an interview before the coronavirus crisis. “I was scared for so long because it was such a freak accident. This was just something that just randomly happened but for other kids, this is happening” every day.

The shooting, the death of a loved one, and the threat of gangs are burdens, but the students won’t let them derail their aspirations.

“Yes, that’s who I am,” Earneasha said of her experience. “But that’s not who I will be and what I will do.”

🔗How trauma is heightened in the pandemic

During the recent online healing circle, students talked about the isolation they’re feeling being at home.

They didn’t stop there. After the online healing circle, the students reached out again on Instagram, offering mental health check-ins to anyone who needs to talk. As part of that check-in, they’ve urged young people to fill out a survey, in which they ask a series of questions. “How are you? Like for real, How are you?” is one of the questions. “What are you most concerned about? What are your worries?” is another. The hashtag couldn’t have been more appropriate: #DetroitYouthSupportingDetroitYouth.

Because of the statewide shutdown of schools, many Detroit students lost a place of security that school provided, leaving many of them disconnected from trusted peers and adults.

The loss of school compounded with past trauma and current fears of the virus could be taxing for youth, which can worsen existing traumatic feelings, said James Henry, a Western Michigan University trauma expert.

That fear could only be heightened during the pandemic, he explained. “ ‘I don’t know what’s gonna happen to my family. Who’s gonna die? What does all this mean?’ That fear is dominant,” he said.

“With the loss of safety and this lack of predictability, you lose relational connections that are the primary factor in helping to mitigate all those [traumas]. We need to seek out ways to be able to find connection,” he said. Social distancing guidelines that dictate people stay 6 feet away from each other mean students must find new ways to connect.

Students flooded the Instagram Live feed with their frustrations over high school life being canceled, their fears over the coronavirus, hopeful prayers that nobody in their families would get sick, and reflections on the uncertainty they’ll confront when they return to school. The feelings were summed up in one comment from a student during the discussion.

“The world will never be the same again.”