Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy

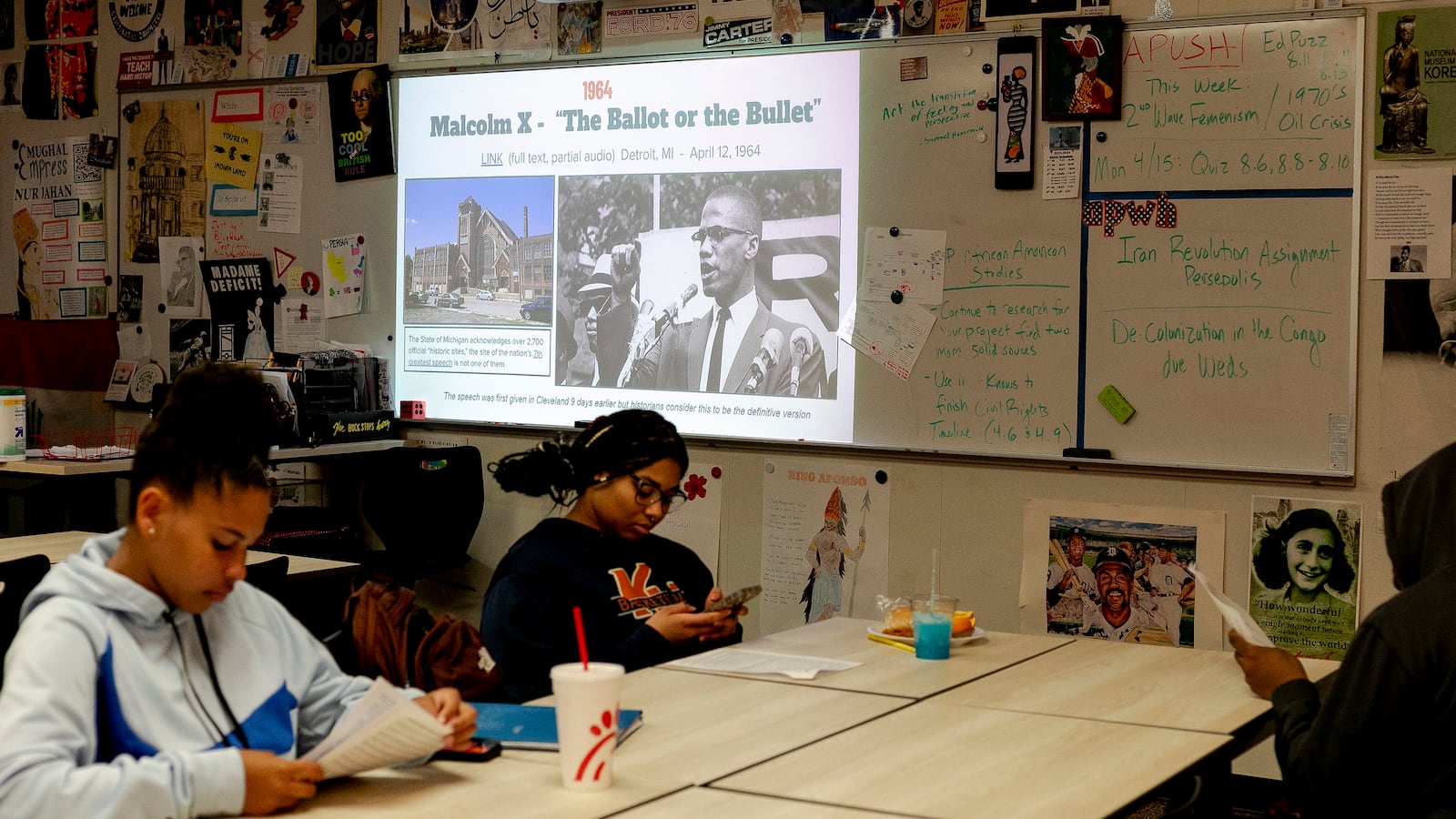

As a crackling recording of Malcolm X’s “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech resonated in the background, eight students took their seats in a classroom at East Kentwood High School. They carried themselves with purpose.

The seniors were not only there to learn history. They showed up to make it.

The course they are taking during fifth period at the west Michigan Kentwood Public Schools campus – Advanced Placement African American Studies – has become a lightning rod among some conservatives who think it teaches so-called “critical race theory” and should be banned. Their school is one of only 17 in the state and 700 across the country to offer it this school year.

For the students, all of whom are Black, it is a chance to delve deeply into diverse perspectives of their own history – which, they emphasize, is American history.

The topic that day: “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” which the slain civil rights leader wrote with Alex Haley.

In the small classroom, made colorful by Black Lives Matter posters, previous students’ artwork, and flags from around the world displayed on its white brick walls, the kids talked in small groups about the latest chapters of the autobiography they had read. They talked about the man Malcolm X was at different points in his life and how his experiences changed his views.

What critics of the course get wrong, said Da’kyiah Sanders outside the East Kentwood classroom, is that the much-debated AP African American Studies course doesn’t teach just one viewpoint.

“It’s everyone’s history,” she said, “every point of view, every perspective.”

Why has the class garnered so much attention?

“Mr. Vriesman, you said there would only be two people on Friday,” one girl said, addressing the observers in the April 15 class, who came close to outnumbering the students in attendance that day. “That’s five people.”

A few of the students were absent that day as they traveled to Washington D.C. The same group spoke about what they’re learning in the pilot program at a State Board of Education meeting earlier this month.

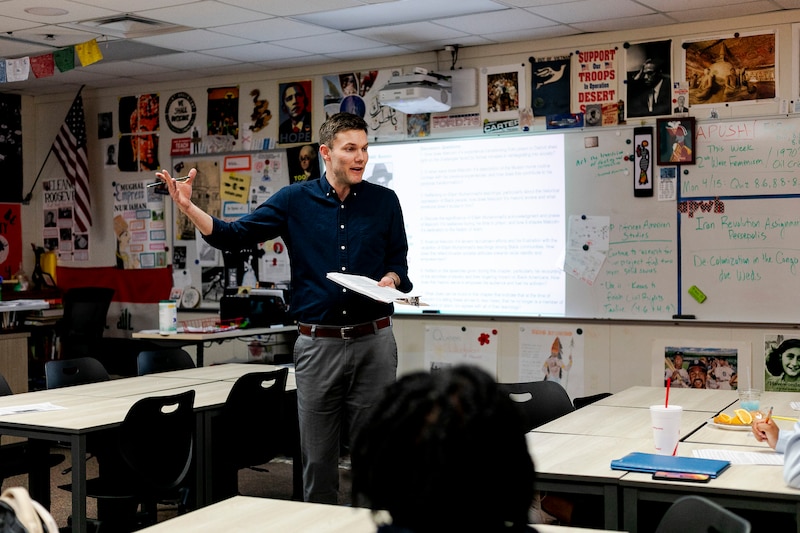

Matt Vriesman, the instructor, is white but focused his final master’s degree research on Black political history in the 20th century. Through that experience, the educator said he noticed the gap between what historians write about Black history and what is included in basic high school texts. He created a website that offers resources and lesson plans that cover race, slavery, and injustice in U.S. history available to all teachers.

Vriesman told the students he wanted to take the time to allow them to be interviewed by reporters so they could share what the experience has meant to them.

“Because, you know, not everyone thinks this class should exist,” he told the class. “And I think your guys’ voices are really important.”

The AP African American Studies course came under fire when it was first piloted in 2022-23, as conservative groups and politicians began to decry so-called “critical race theory” and lessons that teach students about race and racism in America. Republican Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis went as far as banning the class from his state, saying it lacked educational value.

While the College Board, a not-for-profit membership organization that develops syllabi for its Advanced Placement Program, pushed back on such claims, it eliminated mentions of many Black writers and the Black Lives Matter movement from its formal curriculum. The revised framework for the class made those subjects and others “optional.”

Vriesman, who was named the 2023 National History Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Institute, said the conservative argument incorrectly and “ridiculously” concedes there is only one Black perspective.

“There are so many different ideas and strategies and perspectives within the Black community and Black history,” he told Chalkbeat, adding a great deal of the class is about conflicting perspectives.

It covers debates among Black people in the Antebellum period over whether churches should be African churches and whether America is for Black Americans.

“You have David Walker saying, of course it is,” said the teacher. “Others argue after Antebellum that African Americans should leave and move to the Caribbean. There are so many debates within Black history about what’s the best liberation strategy.”

There are plans for the new AP course to officially launch and be available to all high schools in the country in 2024-25.

The overall goal of the college-level course is to use multiple disciplines to examine diverse African American experiences through primary historical sources. Students must engage with sources in a variety of disciplines, such as data, imagery, visual arts, music, news publications, and historical records.

It covers everything from African culture, connections between contemporary Black culture and the African diaspora, political movements, intersections of identity, and multifaceted contexts of social movements. There is room in the curricula to also focus on local Black history.

The class allows the time and space for teachers and students to go more extensively into subjects that might otherwise be left out of U.S. history courses, said East Kentwood senior Adeola Ojo.

“I think they don’t really focus on how African Americans felt,” she said of her previous American history classes. “It’s more about how white Americans may have reacted.”

Seeing history beyond a narrow white perspective can help all students to “understand everyone’s narratives,” said Da’kyiah. Learning different cultural perspectives can also break cycles of oppression and allow for change, she added.

“I wish more people knew about this so that they didn’t stay so ignorant on these topics,” she said, “and so that they could just create a different world, a new world, and not continue to stay along the same path with it.”

The lessons hit home for students

In class on the mid-April day, Da’kyiah and her peers talked about how Malcolm X’s transition from prison to life in Detroit shed light on challenges for formerly incarcerated people reintegrating into society.

As an image of Malcolm X at the Nation of Islam’s Temple No. 1 in Detroit was projected on a white board, the students discussed the significance of the moment for the activist.

“He had never seen Black Americans dressed like that,” said Vriesman of the photo. “All the Black Americans he knew were Christian. They never wore suits and ties.”

A boy in the class said it was the first time Malcolm X describes seeing “pride in being Black.”

“That was perfect AP-level analysis,” said Vriesman of the discussion.

When Malcolm X’s niece, Deborah Jones, visited the class earlier in the semester, she told the students about a school board decision in 1968 to close the predominantly Black Grand Rapids South High School in an effort to racially integrate schools.

The board didn’t listen to the Black community, who wanted it to stay open because it was considered a place of Black excellence, Jones told the class. Instead, it was closed and there were reports Black students were sent to overcrowded, underresourced schools.

Kanyla Tyler, 17, said the lesson on South High hit close to home.

“I ended up asking my family about it, and my granny ended up being part of that last class,” she said.

The lesson opened up a chance for Kanyla to talk with her grandmother about her experience at the school and what it was like to see it shutter.

Lessons on West African culture connected to East Kentwood senior Adeola Ojo’s personal history as well. For the first time in school, she learned about her father’s Nigerian heritage.

“Our first unit taught us about the kingdoms in West Africa and how slaves were taken from there,” she said.

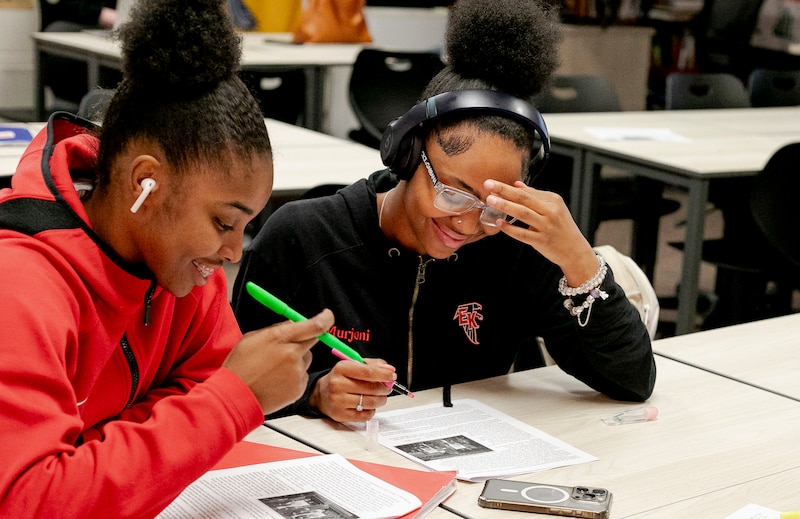

Just before fifth period ended, Kanyla and her classmate, Murjoni McIntosh, 17, stood outside the classroom and smiled when asked what they would say to people who think the course shouldn’t exist.

“I really say skip the haters because Mr. Vriesman makes it a fun experience to actually want to learn more about your culture,” said Murjoni.

“This is like a class where we get to learn more about ourselves and we discover ourselves more,” added Kanyla. “So I would say the same: Skip the haters.”

Then, as the sixth period bell rang and the hallway began to flood with students, the two teens high-fived each other.

Hannah Dellinger covers K-12 education and state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.