Six months after Indiana lawmakers voted to scrap the state’s problem-plagued ISTEP exam, the committee charged with replacing it has made a stunning lack of progress.

With less than three months left before the ISTEP replacement committee must make recommendations to the Indiana General Assembly, the state is no closer to a solution for a new testing system than it was at the start of the process.

And ISTEP is expected to become defunct in 2017 after it is given to students for the last time next spring.

The delay in figuring out what should replace ISTEP has some school advocates wondering if the committee’s charge was too ambitious and suggesting that lawmakers perhaps should not have been so quick to demand a complete dismantling of the state’s testing system without more information about how to rebuild.

Even the architect of the plan to scrap ISTEP acknowledged that the short time frame is a challenge but said the committee has also had to invest time in bringing members up to speed.

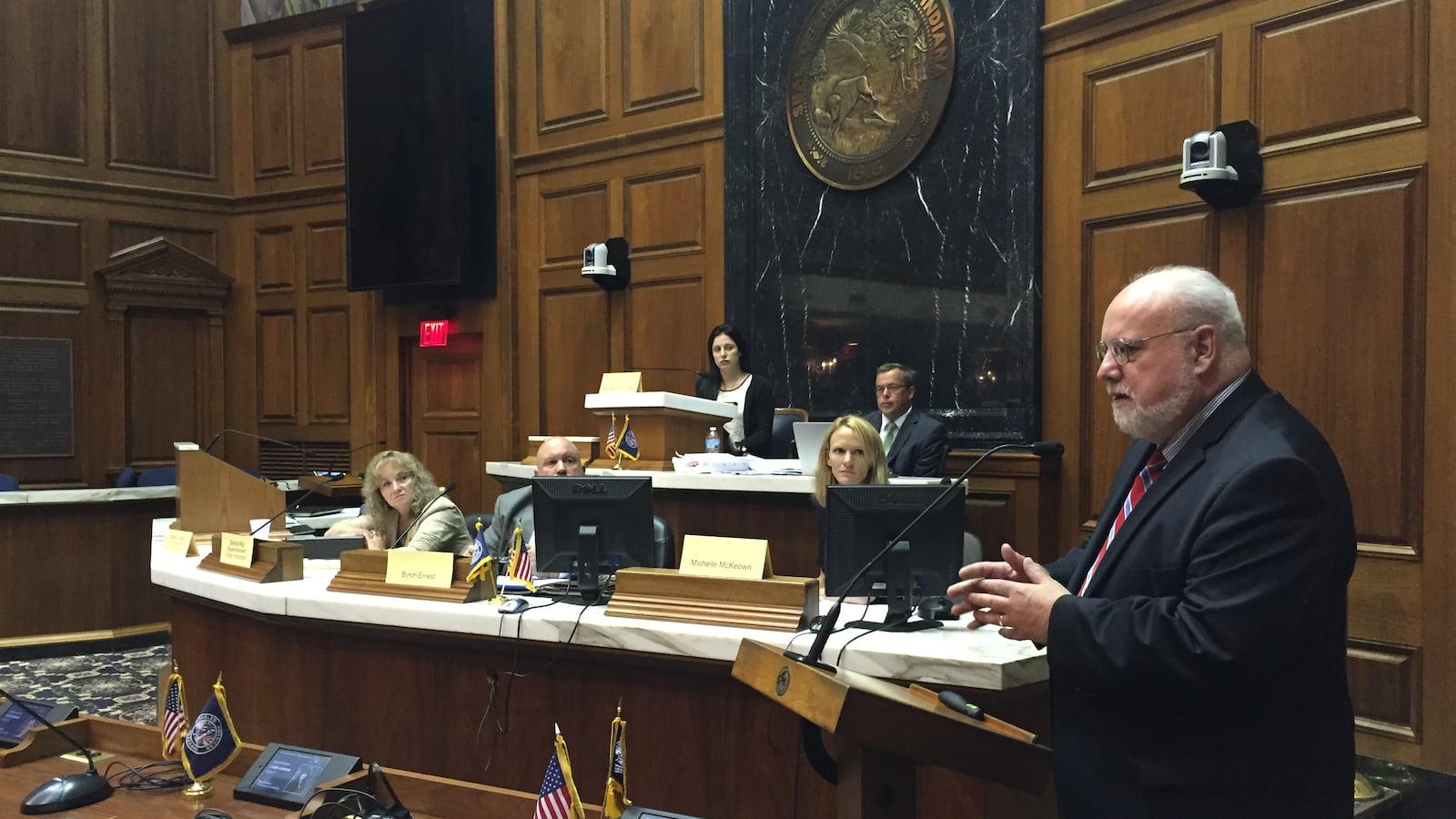

“There’s a lot of people, even on this panel, who are assessment-illiterate,” said committee member Rep. Bob Behning, R-Indianapolis, the House Education Committee chairman who wrote the original bill to repeal ISTEP during the last legislative session. “That’s a significant problem when we talk about what this world is going to look like.”

Whether the ISTEP committee comes up with recommendations or not, current law still says the test will become obsolete in the near future.

Read: They rejected multi-state Common Core exams. Now what?

Indeed, It’s still not clear what new state exams would entail or the differences teachers and schools could expect in the future — if any. The committee has spent hours hearing from experts about the intricacies of test design, with little to no consensus coming out of discussions along the way.

Panelists have barely even begun to discuss the most prominent — and most criticized — test in the system: The English and math test used to test students in grades 3-8.

The panel has spent most of its time focused on some of the lower profile exams, such as those for high school students, which, while important, are given in just one or two grades rather than six.

As the panel used much of a meeting Tuesday to discuss high school tests for the second time, state Superintendent Glenda Ritz acknowledged that there might not be one magic bullet that gets broad support.

“I don’t know that we will ever come to an agreement that will satisfy us all,” Ritz said.

But Ritz and other key committee members say they’re still confident the panel can complete its work to find ways to reduce testing time and cost and explore new options once ISTEP is retired after 2017.

“I am dedicated to changing what we are doing now with this ISTEP test,” Ritz said. “We’ve got the vision … so now we actually have to put the meat on the bones, so to speak.”

That fleshing out of ideas, Ritz says, is coming in October, when the education department will present findings from a “request for information” from test vendors.

“We aren’t evaluating vendors,” said Michele Walker, the education department’s test director. “We’re really looking at the products and services currently out there and in development so (the panel) can have a better handle on what’s possible.”

Steve Baker, a committee member and principal at Bluffton High School, said he has no control over the politics at play or the timeline for their decisions — he’s been part of many policy groups, and sometimes, this is how it works.

“I’ve got to keep my focus on the goal and the end game, and not let other things distract me from that,” Baker said. “If I didn’t have this attitude, I would come in with a headache, and leave with a headache.”