In November of my junior year of high school, I watched from outside my body as I spoke before the Newark Board of Education. As someone who had always shied away from being under any kind of spotlight, it was uncharacteristic for me to be delivering this speech. However, when it was time to decide if I was going to speak up or remain silent, I remembered a quote by the incomparable writer Zora Neale Hurston: “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.”

The passage of time has blurred the details of that night about a year ago, but I distinctly remember that the air in the room had shifted when I was done speaking. It was as if I could see on the faces of the adults before me that a rug had been pulled out from beneath them. I had just brought a significant amount of attention to an issue that most Newarkers seemed to know about, even as few spoke up: the culture of segregated schools in our city. (Many schools here are either overwhelmingly Black or overwhelmingly Latino.)

At Newark School of Global Studies, where I was enrolled, the situation had escalated from kids teasing each other to the minority Black student population being the targets of racist harassment and hostility. At the time, the high school had been open just three years, and from the beginning, students spoke among themselves about the divisions and racism that marred their experience there.

During my sophomore year, a number of my friends and I attempted to rationalize the way we were being treated. Maybe our classmates just didn’t like us, we thought. But by the end of that school year, it was impossible to deny that there was something larger at play and that the institution at which we were enrolled was part of the problem.

One instance in particular that has stuck with me took place in June of my sophomore year. Ironically, it happened to be our school’s cultural appreciation day. I had just finished taking the written exam for my driver’s ed class and was preparing to tell my favorite teacher that it had gone well. While en route to her class, I felt someone’s fingers digging into my arm and pulling me to the side of the hallway.

I turned to realize that the person pulling me was my best friend and that she was visibly upset. The sentence that soon fell from her lips would alter the rest of my high school career.

“Reuben [not his real name] shoved me and called me a n—,” my friend told me.

For a moment, time stood completely still. We stood completely still. I could hear and feel the bass drum that replaced our heartbeats. We did not speak, nor could we meet each other’s gaze. Very briefly, I considered confronting the boy who had uttered that hateful word but ultimately realized that could make the situation worse. Instead, I rushed over to the first teacher I saw and reported this incident. This wasn’t the first time Black students at Global Studies had been subject to harassment and abuse. Reports, both written and verbal, had been filed, but nothing seemed to change. And this time around was no different.

I could also sense how powerless my friends felt, how defeated.

My school’s failure to put an end to this racist bullying made me feel like my voice did not matter. Or worse, like I did not have a voice at all. I could also sense how powerless my friends felt, how defeated. We had tried not to let the circumstances get the best of us, but it had begun to take a toll on our grades and our mental health. I would come to school ready and willing to learn, only to be met with a racial slur or a bigoted joke vocalized in the middle of a class period. It was eating away at me. Turning in assignments became the very least of my worries.

In dire need of comfort and community, I decided to create a Black Student Union — not only because Black students deserved a safe space but also because it felt abundantly clear that no one in power was going to show up and save us. We would have to save ourselves.

It was that belief that eventually led members of our student union to that November 2022 Newark Board of Education meeting. We had no idea what would come of us sharing our story there. This was our opportunity to truly make ourselves heard.

And yet the situation inside our school building did not improve. By the following school year, some Black students, including myself, had decided to transfer to a different high school. (Chalkbeat Newark requested the number of students who transferred out of Global Studies during the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years, but the request was denied, citing student privacy.)

In January of this year, the Newark Board of Education commissioned a review of the racial and cultural climate at Global Studies. While the report has not been publicly released, some of its recommendations have been. According to the report, the Newark district must look at how “anti-Blackness and other deficit beliefs” impact its schools. It also calls for Newark Public Schools to create spaces for difficult conversations about race and help school staff identify and fill “cultural gaps” in their practices. While this is hardly a solution, I hope that it results in a safer and more inclusive environment for everyone.

Such changes won’t have happened on the timeline many of us would have wished for, but it’s never too late for our leaders to hold themselves accountable and right their wrongs. In fact, every Black student in the city depends on them doing so. As I told the members of the Newark Board of Education at that fateful meeting: “At the very least, Black children deserve to feel loved, valued, and respected.”

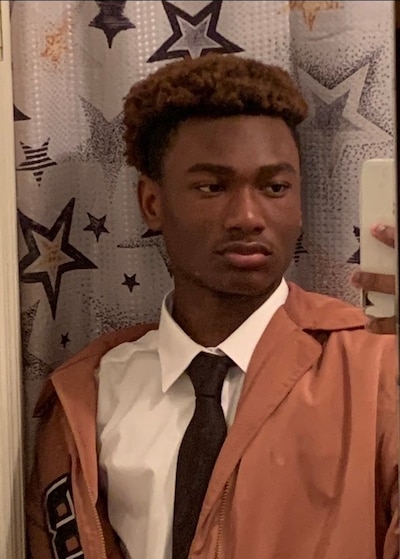

David Allen is a high school senior who started a Black Student Union at his former high school to combat racial injustice. It was his admiration for literary giants like Zora Neale Hurston and James Baldwin that ultimately guided him toward becoming a student activist. Earlier this year, he was awarded the “Celebrating Black Resistance Award” by the City of Newark.