This year, the city won’t be giving principals a college performance report that has been hailed as a state and national model.

Since 2010, high school principals have been receiving “Where Are They Now?” reports that provide a detailed picture of a student’s academic path from high school through college. In recent years, officials also began compiling data for elementary and middle school principals about their former students’ success in older grades.

The reports have been scrapped for this year and are being reviewed in part because they weren’t used by principals, a spokeswoman for the education department said. Their elimination is the latest change to the way student data is being used under Chancellor Carmen Fariña and another departure from the systems set up by her predecessors under the Bloomberg administration.

The city is preparing to phase out ARIS, the student-data management system, and has already replaced the progress reports, which included A-F letter grades, that Bloomberg used to rank and evaluate schools. Earlier this month, the Department of Education released “School Quality Snapshots” intended for parents and “School Quality Guides,” which offer a larger set of student performance data. Fariña has also brought in a new group of advisors to help her study how best to use data for evaluating schools, Capital New York reported Wednesday.

While some of those changes were announced to great fanfare, sparking debates over school accountability, getting rid of the Where Are They Now reports caused fewer ripples. They have never been released to the public and weren’t used for high stakes, two factors that helped them avoid the scrutiny that surrounded Bloomberg’s progress reports.

But their demise has raised eyebrows for at least one constituency: education researchers, who gave the reports rave reviews as a forward-thinking approach to using data in schools.

“There aren’t a lot of data systems out there that are useful and usable,” said Leslie Siskin, a research professor at New York University. “The Where Are They Nows were a pretty good step toward providing data to schools, better than most in the country.”

The city will continue to track and provide data used to compile the reports, spokeswoman Devora Kaye said. Some is already available in the school quality guides and snapshots, including what kinds of colleges former students most often attend and what percentage are still enrolled six and 18 months after they graduate high school.

“The rest of the information that was historically provided in these reports will be provided in a new workbook to schools in the spring,” Kaye said.

While the reports are on their way out in the city, they’re being used as a model elsewhere. On Monday, State Education Commissioner John King unveiled a slimmed down version of the reports, which were also dubbed Where Are They Now reports, for all schools in the state.

The focus on college preparation also received attention this week with the release of a report Wednesday that showed the vast majority of high school graduates who enrolled in college were falling behind. Of 21,000 city students who graduated high school and enrolled in a two-year or four-year college in the fall of 2006, just 36 percent of them received a degree four years later, according to the Research Alliance at New York University.

James Kemple, executive director of the Alliance, said the research “is raising at least as many questions as it is answering” because the thought that high schools should prepare students for college is still a new one. For decades, high school diplomas were enough for a high-paying job, but one 2013 study estimated that 65 percent of jobs in 2020 will require a post-secondary education or some training beyond high school.

Siskin said principals college data of their former students were an important first step to help them figure out how to better prepare students while they’re still in high school, such as more intensive counseling services during the college application process or offering more advanced courses.

“This is a huge shift, so they need all the useful tools they can get,” Siskin said.

What are the Where Are They Now reports?

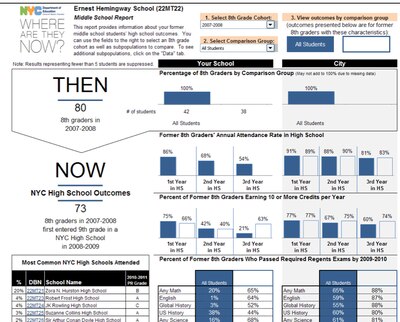

On the spreadsheets, principals can see how many of their students matriculated to college, the type of college they attended, and how many were still enrolled through four semesters. Students at the City University of New York are tracked more closely on the reports, which show how many took remediation classes, what their average GPA was and what their class passing rates were.

One of the report’s tabs features an interactive dashboard that allows user to toggle between graduating classes and slice them by seven different student demographic groups.

Some principals said that while they found the reports interesting, they weren’t always useful.

Williamsburg Preparatory Principal Michael Shadrick remembered looking at how many of the students who graduated from his high school were making it to their fourth semester of college, for example, but not having much of an idea about what he could to improve that number.

“They’re very frustrating because there is a degree of powerlessness,” Shadrick said of the reports.

Others said the detailed results were a revelation. Stephen Duch, the longtime principal of Hillcrest High School in Queens who retired last year, called the data “eye-opening.”

For years, Duch said, he believed that his school’s high graduation rates meant Hillcrest students were succeeding in college. But Duch said his school’s “Where Are They Now” revealed that fewer students were persisting in college than the school administrators had thought.

“It made us take a step back and look at what seniors did in making transition from high school to college,” said Duch, who also asked alumni to send their work back to Hillcrest to help assess if his school’s work was adequately preparing students for college assignments.

Post-secondary readiness data culled from the reports were first used for accountability purposes in 2012, when schools started receiving points for the percentage of students who passed college-level exams; met CUNY proficiency standards; or entered college, the military, or a work training program.

At the time, Kim Nauer and research colleagues at the Center for New York City Affairs had embedded themselves in 12 high schools, where she said the data-driven focus on college readiness had created a sense of urgency around the issue.

“This is the first case where I feel like I witnessed high schools really improve their behavior around preparing students for college,” said Nauer, who authored a 2013 report urging the city’s next chancellor to prioritize college-readiness over more traditional academic measures of school success.

Nauer said that she would feel comfortable with the city’s decision to dismantle the reports as long as officials continued to collect and share the underlying data. But she questioned why the city is not planning provide most of that information to schools until the spring.

“You have the whole infrastructure set up to do that,” Nauer said. “Why wouldn’t you send that out to people?”