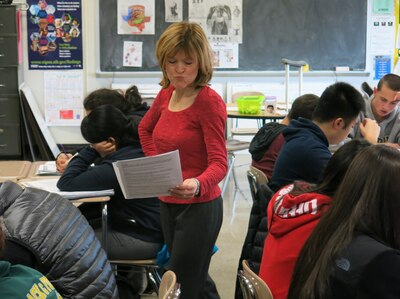

After class one recent afternoon at New Dorp High School on Staten Island, health and science teacher Theresa Dunlap Kutza was comically busy.

Buzzing around her room in a festive red sweater, the former nurse collected permission slips for an upcoming class trip to view a live surgery, thanked some students for creating the holiday decorations she’d asked for (photos of famous scientists in Santa hats), and fielded a reporter’s questions about the award she won this month for exceptional science teaching.

“I feel like I got an award for doing something I love!” said Kutza, who has taught at New Dorp for the past 13 years.

When Kutza first moved to the classroom after 17 years working in hospitals, she applied her nurse’s efficiency to teaching, making sure to cover the entire textbook each year. But over time, she realized that to absorb the material, students really have to do something with it.

So now, Kutza, who was one of seven city educators this year to win a $5,000 Sloan Award for Excellence in Teaching Science and Mathematics, has her freshmen handle real oysters and debate the best way to contain Ebola. In her neuroscience class, students study meditation and hypothetical zombie brains. And in anatomy and physiology, Kutza asks them to solve actual medical mysteries.

“She takes everything beyond the classroom,” said Principal Deirdre DeAngelis, adding that faculty and students alike celebrated when Kutza won the award this month, which also brings $2,500 to each winner’s school. “Everyone felt like, ‘You deserve it.’”

Chalkbeat stopped by Kutza’s college-level anatomy and physiology class last week, where students played the part of doctors trying to diagnose a woman’s illness based on a case study Kutza found in a magazine. Below are the highlights from the lesson, which came after a unit on cells.

10:28 a.m. Not one to waste time, Kutza started class promptly at the bell, asking students to describe in their notebooks different kinds of membranes.

That was followed by a brief discussion, where Kutza reminded students of the distinction between serous and mucous membranes.

“If you were to miniaturize yourself and walk along the mucus membrane,” she said, noting its porousness, “you’d be able to get outside of the body.”

10:41 a.m. Now they were ready to meet the sick woman in the case study. After Kutza reminded the students to take detailed notes like doctors do, she read them the story.

The middle-aged woman had lost consciousness in a department store bathroom, surrounded by a pool of bloody diarrhea, Kutza read. Paramedics found her heart racing and her blood pressure dangerously low. Later, it was determined that her blood had lost its ability to clot.

10:46 a.m. The students’ first task was to list clues they had heard. They noted that the woman took antidepressants and had been in good health before the incident, except for one time when she’d suffered similar symptoms.

They also ventured some possible causes. One boy suggested that she might have too few platelets, the cells that stop bleeding, while another said she could suffer from hemophilia, a disorder that keeps blood from clotting.

Kutza then asked them to decide what tests to order or referrals to make.

“You’re the doctor,” she told the students. “What are you going to do?”

10:50 a.m. The students conferred with one another, then recommended ordering a blood count, a colonoscopy, and an investigation into the woman’s

medication, in case it caused any relevant side effects.

They were on the right track. The doctor in the story had, in fact, conducted a colonoscopy, Kutza read, and it turned out that the woman’s medication was part of the problem. Now, Kutza told the students, it was finally time to diagnose the cause of the medical scare.

11:04 a.m. Before class, Kutza had cautioned a visitor that the students might not be able to solve the mystery. Now, she told the class that anyone who did would get extra credit on an upcoming test. She asked the students to deliberate, but within 10 seconds a girl raised her hand.

“It could be a problem with the mast cells,” the girl said, referring to certain white blood cells that produce chemicals that can cause low blood pressure and also stop blood from clotting. Another girl added, “She might have an excessive amount of mast cells.”

They were exactly right: The woman suffered from a rare disease in which the body has too many of those cells, and certain medications can trigger the cells to cause the symptoms the woman experienced. The two girls and the boy who had flagged the antidepressants all received extra credit.

“I’m really proud of you guys,” Kutza said. “That was good.”

After class, junior Noah Putney, who plans to study medicine, said case studies like that remind him why he should care about cells and membranes.

“You get to see how what you’re learning can actually apply to what you’re going to do in the future,” he said.