As a long-time elementary school occupational therapist and as a parent, I know firsthand the benefits of free movement on children’s physical and emotional well-being. Making the time and finding the space for physical activity improves physical health, attention, self-regulation, mood, and is, you know, fun (because children should also get to have fun)!

As we grapple with reopening schools in the middle of an unprecedented public health crisis, New York City is proposing children and staff return to in-person learning with enormous restrictions inside school buildings. These restrictions are about maintaining physical distance from peers and following safety measures, such as wearing face coverings, washing hands, and avoiding shared materials. These physical restrictions create brand new social restrictions — and we cannot yet measure the psychological impact of children being kept six feet apart, interacting with fewer friends, and seeing only half of the faces of those they do see. On the days children are learning remotely, they face another set of restrictions brought on by hours of screens and video conferencing.

The concept of “least restrictive environment” is a part of the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, and it means that children who receive special education should learn alongside peers who are in general education to the “maximum extent appropriate.” How can we use the idea of “least restrictive environments” to consider what all students will need from their schools this fall? How can we make sure that students’ surroundings won’t limit their education, but enhance it?

The coronavirus crisis offers an opportunity to reimagine elementary school education by moving it outdoors. Even before COVID-19, American children were sitting more and moving less, creating deficits in health and wellness, and affecting attention and self regulation, studies have shown.

Learning outdoors gives us a chance to have children move more, improving their gross motor skills, strength, endurance, and coordination. Learning outdoors gives children a chance to learn through play, which is essential for appropriate child development. Learning outdoors offers sensory experiences to support improved self-regulation and opportunities to promote and expand executive functioning skills. In my experience as a school-based occupational therapist, I’ve seen how much more grounded, focused, and ready to learn children can be after intensive movement-based play. And because the coronavirus is less likely to spread outdoors, student movement and their social interactions can be far less restricted outside than in school buildings.

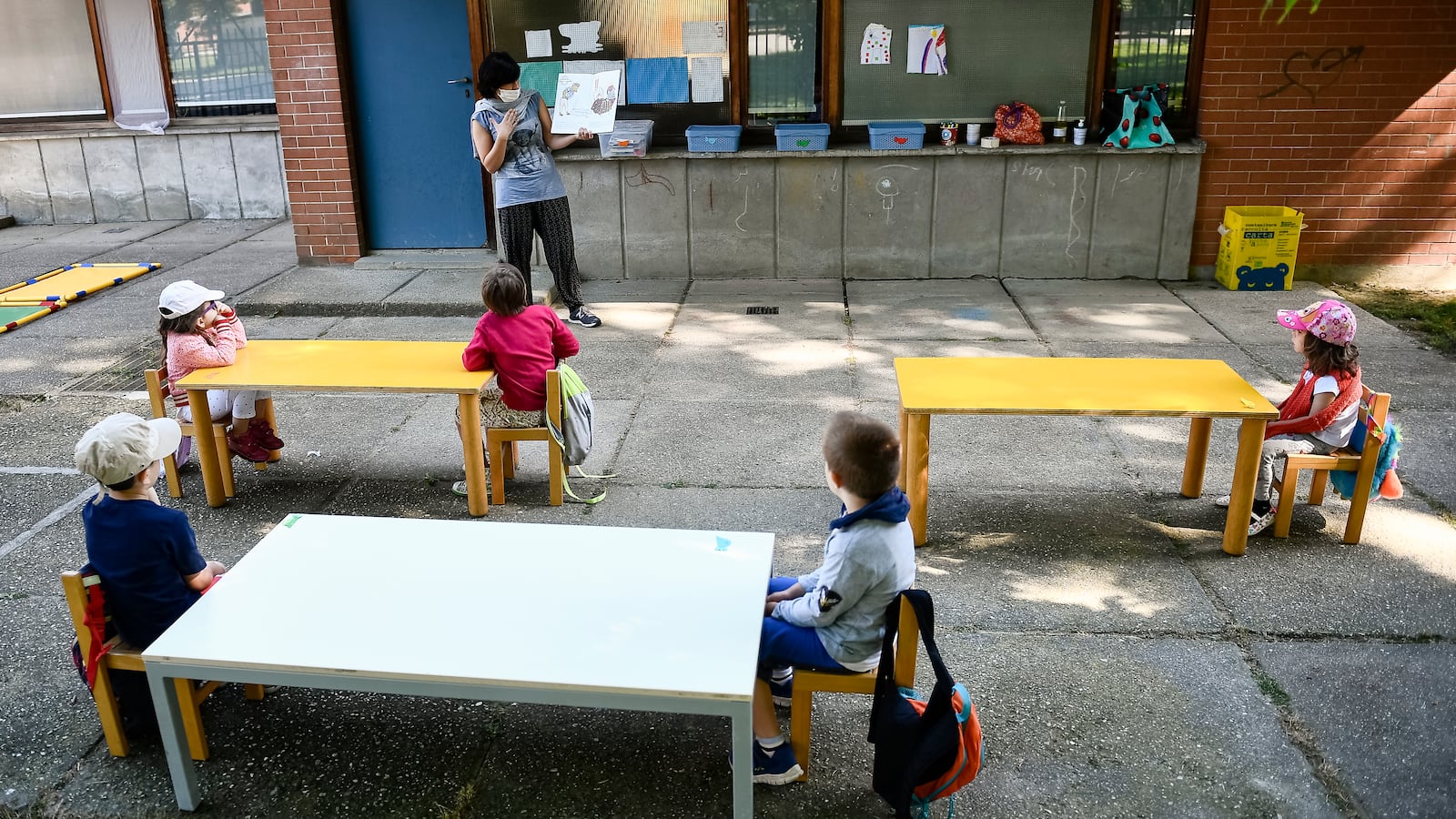

Outside learning is more than being able to run and move and play. It’s exploring parks and neighborhoods, actively learning about the communities children live in and the nature that can be found in the corners of our city. It’s circle time and morning meeting, but on a closed street or in the recess yard. It’s readers’ and writers’ workshops, but under a tree or in the shade of a building. It’s using rocks and sticks as math manipulatives, and teaching emerging writers letter formations with good old fashioned chalk on asphalt. It is occupational, physical, and speech therapy on a play structure, using the power of play to reach therapeutic goals. The very act of taking school outside removes restrictions on what we imagine learning to be.

Of course, outdoor learning isn’t a perfect solution. It poses its own set of logistical challenges and restrictions. How do we fund it when schools are already facing major (and outrageous) funding cuts? What don’t we fund in order to make this happen? How do we implement it equitably so that schools with fewer resources or don’t have nearby accessible outdoor space can also explore this option? (On this front, some lawmakers and public education advocates are pushing to close some school-adjacent city streets to traffic.)

Yes, there are concerns regarding bathroom access and inclement weather. As they say in Scandinavia, “There is no such as thing as bad weather, only bad clothes” — but how do we make sure all children have access to good outdoor clothes? As with all of the other options on the table, outdoor learning requires adequate and equitable funding to ensure these spaces are safe and appropriate for the students they serve.

Returning to school is a Catch-22. As a parent, I want my children safe, which means keeping them home and learning remotely. As a parent, I also want my children learning in the best context possible, which means in-person and alongside their friends. As an occupational therapist, I want to stay healthy and protect my family, which means working remotely. As an occupational therapist, I want to provide the best therapy possible, which means doing it in person and doing that as safely as possible.

There is no solution that works perfectly. They all come with hurdles and new restrictions in the age of COVID-19. But the least restrictive learning environment this fall? That would be outdoors.

Lisa Raymond-Tolan is a school-based occupational therapist in Brooklyn, a mom to two public school students, and co-president of Indivisible Nation BK.