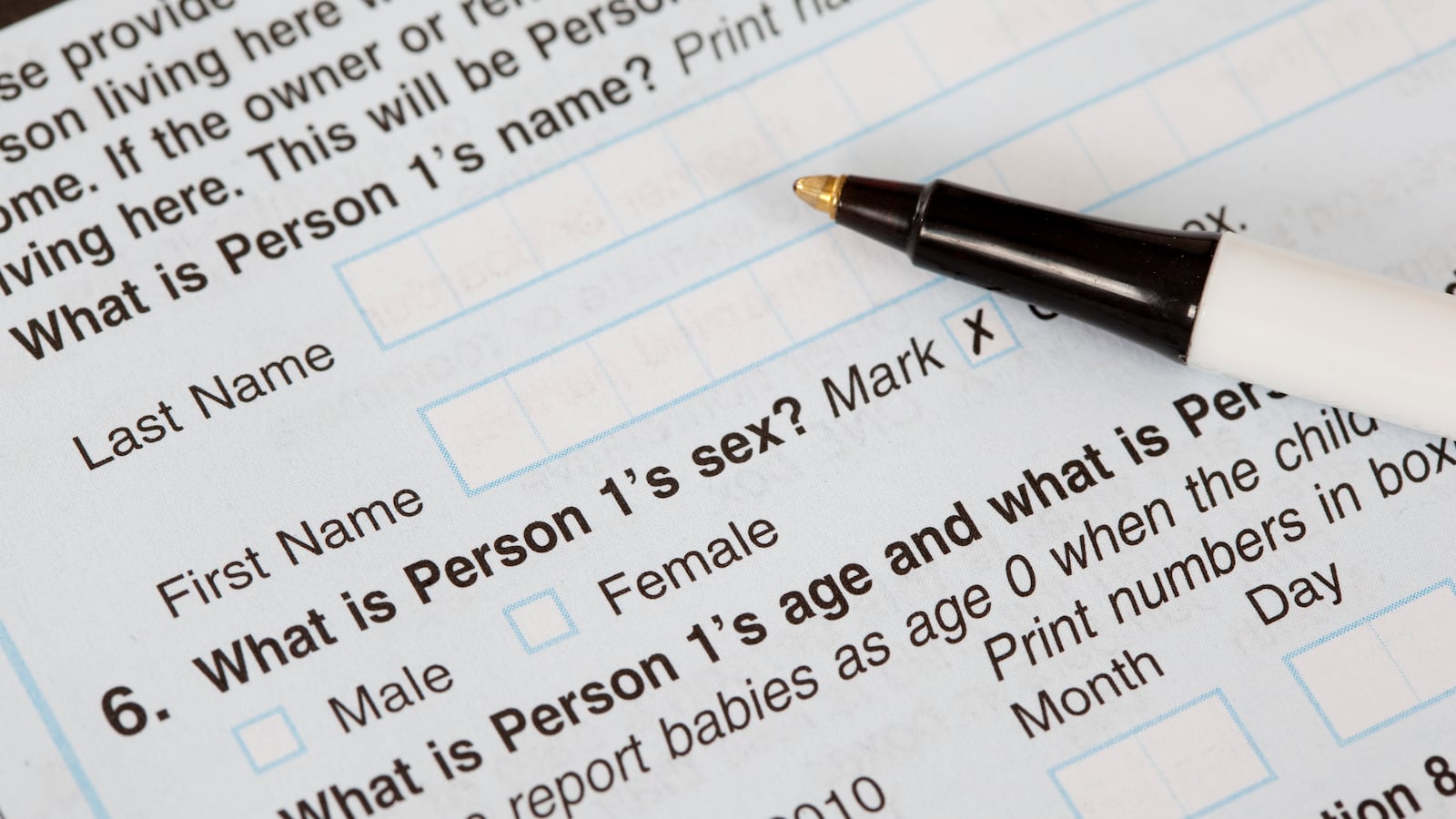

Peering over my father’s shoulder, I see him twirling a pen as he considers this question on the 2020 Census: What is Person 1’s race? My dad hesitates, and I look closer at the paper to see why he looked so unsure of which box to check.

These were the choices: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White (with further selections for various Hispanic and Asian sub-groups). None of these “labels” apply to our family.

So, what are we?

My parents immigrated from Morocco. Most of my grandparents have Arab ancestry with the exception of my maternal grandpa, who is Amazigh, a group indigenous to North Africa and parts of Mauritania, northern Mali, and northern Niger. With white skin and deep roots in Africa, I don’t identify as white, African American, or any other categories on the census. The federal government, however, calls those of us from the Middle East and North Africa — from Morocco, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iran, and elsewhere in the region — white.

But as someone with an ethnic name who has encountered weird stares and biased remarks for being a hijabi Arab American, I believe that the privileges that come with being white do not necessarily align with my experiences. The laughs I hear after the teacher mispronounces my name while reading off the attendance sheet or the occasional snide remarks about terrorism from students are just a couple of the instances when I have felt like an outsider.

After watching my dad consider the census categories and ultimately pick White, I returned to my room and thought hard about my origins and identity, seemingly limited by the choices on a federal form. I didn’t feel adequately represented or seen in my entirety by any of the racial categories on federal forms.

Sure, the census offers a fill-in-the-blank option, but the form lists people from countries in North Africa and the Middle East, such as Egypt and Lebanon, under White.

Nada Maghabouleh, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Toronto, has said that many people of Middle Eastern and North African descent aren’t perceived — and don’t perceive themselves — as white. As she told NPR, “some of their experiences were actually closer to communities of color in the U.S,” given the discrimination many of us face.

With white skin and deep roots in Africa, I don’t identify as white, African American, or any other categories on the census.

I discovered that my friends and other family members shared the same experiences. Zineb Hbabou, a friend from New York City, was frustrated by the lack of representation on college and government-issued forms and surveys. She believes that the allocation of services for these groups is hindered by this exclusion, with “major implications for social justice.” My cousin Ayah Maarouf described her struggle like this: “We are put under the title of one thing, yet, the treatment we receive from the media and the people around us is nowhere near the same. I feel more closely connected to communities of color than the white collective.”

A scroll through TikTok or Instagram reveals that many others feel ambivalent about checking a racial category on government forms, as well as college and other applications. I am a high-school senior and have begun to apply to colleges. Questions about my ethnicity, with no Middle Eastern/North African, or MENA, option, make me feel uncomfortable and unseen. With so many institutions labeling us as white, people of Arab ancestry are often rendered invisible in official statistics, which health and education researchers may rely on.

Although MENA is not an official category on the U.S. Census yet, I’ve realized there are still so many ways I can promote this change, retain my identity, and connect with others who share a similar background. I repost social media threads to shed light on the lack of representation for MENA individuals, engage in discussions with friends in and out of the MENA community, and sign petitions to add another racial category to official forms. I also join clubs and attend events for Arabs, North Africans, and people of Middle Eastern descent. I feel especially proud of my heritage among others who share it. There is so much work that needs to be done. But these small initiatives have brought me closer to understanding who I am and connected me with those whose experiences mirror my own.

Douae Maarouf is a senior at the Baccalaureate School for Global Education. She is an Arab and Amazigh Moroccan who lives in Queens, New York. Douae is a food photographer, blogger, and recipe developer for Sarah’s Kitchen. In her free time, she finds joy in reading, creating episodes for her podcast Talking Under the Stars, exploring NYC, and binging “Criminal Minds” episodes.