My tailbone presses against the wall as I sink to my bedroom floor, breathless and unable to move. I can’t think clearly. Just breathe in, and breathe out, I tell myself. For a moment, air floods my lungs. But my face is sticky with snot and hot tears, and soon, it feels like there’s nothing left to breathe in. A coarse breath escapes my throat, almost like a croak. All I can do is melt into myself, knowing I’ll wake up tomorrow and repeat this whole excruciating routine.

Day after day, this was what the first three months of my freshman year of high school looked like.

I’d spend an hour and a half each morning getting ready for school, straightening my hair, perfecting my makeup, changing my clothes until they felt “right.” I believed that if I did everything a certain way, my fears wouldn’t come true, and I’d be able to get out of the car when we arrived at my Brooklyn school.

Like many other teens, I worried about what others thought of me and about my grades. I didn’t just worry about these things, though. The worries consumed me.

I had missed a few days of school in the early fall because I’d caught a cold. Despite my symptoms being gone within a day or two, I struggled to return to school. Over the next few months, I would often wake up and feel incapable of going to school. I went from missing a day here and there to missing weeks at a time.

It was a lonely experience, but I’m hardly alone. Before COVID, an estimated 1% to 5% of students showed signs of school refusal, or emotional distress that causes children and teens to miss school, often for extended stretches. In the years since the pandemic, though, more adolescents have experienced anxiety, depression, traumatic stress, and other mental health challenges that make school refusal more likely.

From the outside, it probably looked like I was playing hooky. Even my parents started to wonder if I was just being lazy and stubborn. In reality, I was overwhelmed by anxiety that continued to build every day, whether I went to school or not.

Related story: How NYC students are navigating post-COVID school

After three months of being in a near-constant state of panic, I reached a breaking point. It was early January of my freshman year, a week before our midterms, and I was in an unrelenting battle with my mind. Going to school had begun to feel impossible, and I stopped going entirely.

I couldn’t stand being present in my own life, so I disappeared into TV and movies. It felt easier to exist in a world where I didn’t.

But for two months after I stopped going to school, I would still get up every morning, get ready, get in the car, and panic. Like clockwork. I watched from inside the car as my peers filed into the building as if it were no big deal. Watching them made me wonder: What’s so wrong with me? Why can’t I function like everyone else?

I would tell myself that my one job as a teenager was to go to school every day, and I was failing at that. It was embarrassing.

Meanwhile, life outside kept moving. Classmates would text me and ask where I had been, or if something was wrong, and I would respond with something along the lines of “Yeah, I’m good, just dealing with stuff.” I couldn’t bring myself to tell them what was really going on: that I’m afraid of coming to school, and I don’t know why.

A therapist suggested treatment in the form of an Intensive Outpatient Program, or IOP. It wasn’t a residential program — I would sleep at home — but it involved me getting a full day of therapy Monday through Friday. When my parents felt like they had exhausted every other resource available to us, they enrolled me at the Anxiety Institute in Madison, New Jersey, where I would spend the remainder of my freshman year.

Soon after I arrived there, I was diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Better known as OCD, the disorder often causes people to have unwanted, intrusive thoughts and to perform rituals or mental habits as a way to ease their anxiety.

There are many misconceptions surrounding OCD, and with more than 15 subtypes, it’s a different experience for everyone. The stereotypical traits associated with it, like being superstitious and hyper-organized, are just a fraction of what people with OCD experience. For some, it’s false memories or dissociation; for others, obsessions and compulsions can be contamination-related or religious. For me, it involved bodily functions and a need for things to feel “just right.”

But if you met me when my OCD symptoms were at their worst, I may have appeared outgoing and high-functioning. On the inside, though, I was busy convincing myself that something terrible would happen and then doing everything I could to prevent it, even if it didn’t make logical sense.

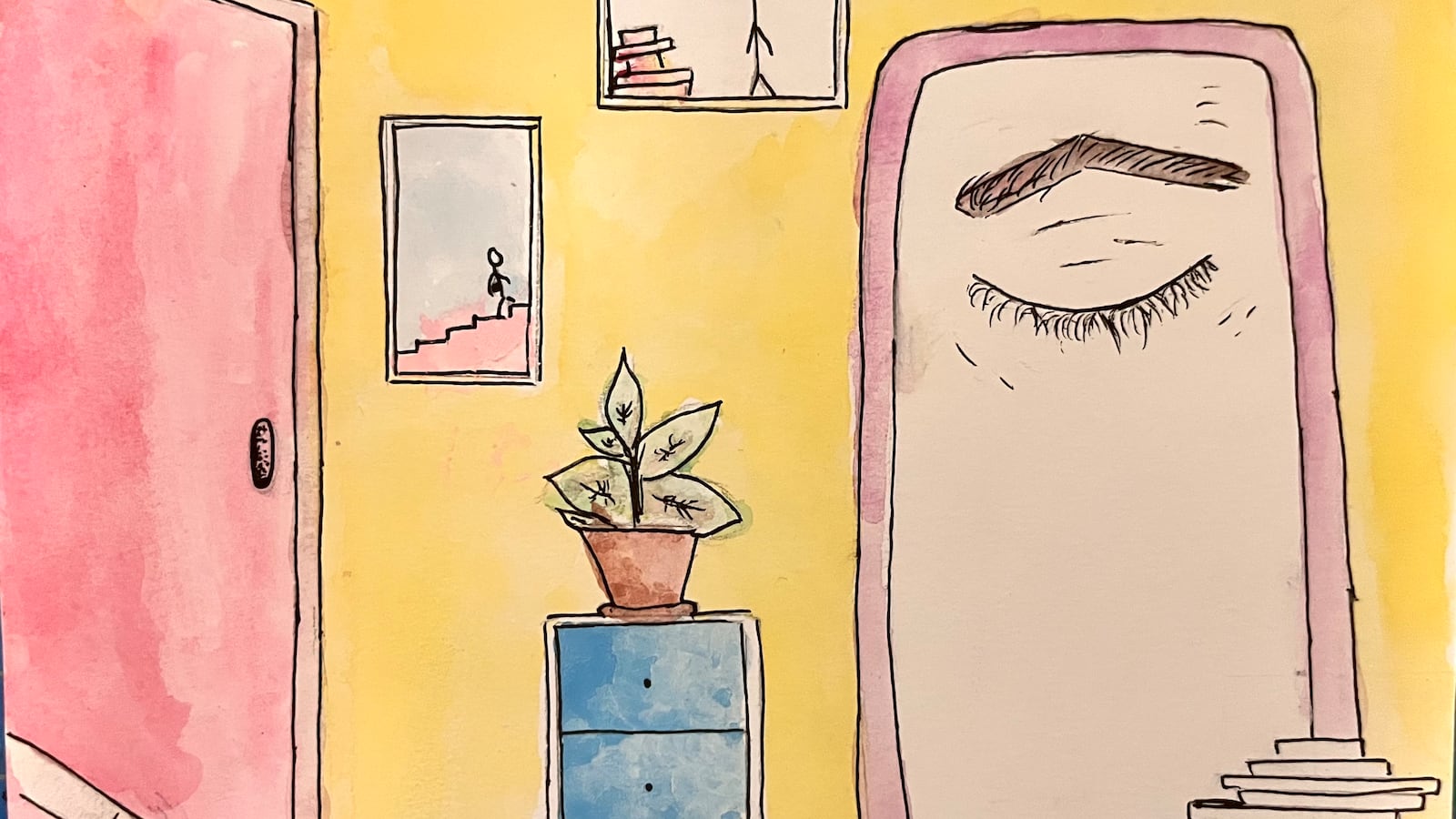

At the Anxiety Institute, I was treated with a range of therapies. There was art therapy, where we did things like draw what anxiety felt like. There was fitness therapy, where I could earn the physical education credits needed to graduate high school on time. On nice days, we would take long walks or play soccer in a nearby park; on other days, we would practice yoga inside. There was group therapy, where we discussed topics such as relaxation and mindfulness techniques and the distinction and relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Most importantly, there was Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, focusing on exposure therapy. This means that patients are gradually exposed to their fears in a safe and controlled environment, under the guidance of a therapist. The goal was to build up my tolerance for anxiety and discomfort.

In one early exposure, to address general fears about being judged by others, I was tasked with trying to order a Big Mac in a Burger King (where, for the record, they don’t sell Big Macs); in another, I had to ask a Whole Foods worker where in the store I could find a bunny.

As my treatment progressed, the exposures targeted my specific anxieties and compulsions. No makeup, chipped nails, singing “Happy Birthday” in public, writing without backspacing. I was tasked with doing these things that triggered spirals of fear and shame.

What if people thought I was gross, awkward, unhinged?

If my nails weren’t perfect, my already clean hands felt sticky and covered in goo. I repainted them again and again, chasing relief that never lasted. Exposure therapy helped me slowly get used to sitting in that discomfort and not trying to fix it right away.

It helped with my social anxiety and online interactions, too. One exposure I’ll never forget was when my therapist had me post a completely random photo on my public Instagram story and leave it up for 20 minutes. I took a picture of my foot in a Croc — and anxiously watched the view count go up. I was convinced people were judging me, wondering what was wrong with me, thinking I was weird or cringey or embarrassing.

Turns out, no one said anything. Everything was still OK. That was the whole point. Exposure therapy taught me that I can feel uncomfortable and nothing terrible will happen. It is just a feeling, and eventually, feelings pass.

Every day, after treatment and before heading home, I would log into Google Classroom. I did my best to keep up with the schoolwork and homework that my teachers back in Brooklyn had assigned. It was hard missing out on in-class lessons and interactions. It was exhausting to apply myself after hours of therapy and exposures.

In May 2023, after about three months of treatment, I graduated from the Anxiety Institute feeling like a different person than when I entered. Someone who understands that you can’t control what happens, but you can control how you respond to it. Someone who is still terrified of going to school, but also someone capable of returning to school.

My treatment taught me that I can do hard things. We all can.

In the two years since, I’ve changed and evolved even more, though it’s still difficult to look back on that time without feeling a little shaken. I want people to know that my school refusal wasn’t just me deciding not to go to class; it was a perfect storm of fear, pressure, shame, and confusion that I needed to understand before I could address it.

Today, school no longer feels like something I’m constantly trying to survive. The workload is still stressful at times, and I still get overwhelmed, as many teens do, but I no longer approach school with such an extreme, perfectionist mindset. Having a group of understanding friends helps.

I’ve also learned to see and embrace the beauty in imperfection. And my advice to those facing similar struggles is this: Things don’t have to be perfect to be wonderful, and at the end of the day, what’s meant to be will be.

Anika Merkin, a 2024-25 Chalkbeat Student Voices fellow, is a junior at Brooklyn Prospect High School in Brooklyn, New York. She finds comfort in cuddling with her cat, watching movies, and making pottery. Through her writing, she hopes to create a space for honesty, connection, and appreciation for the things in life that often go unnoticed.