This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

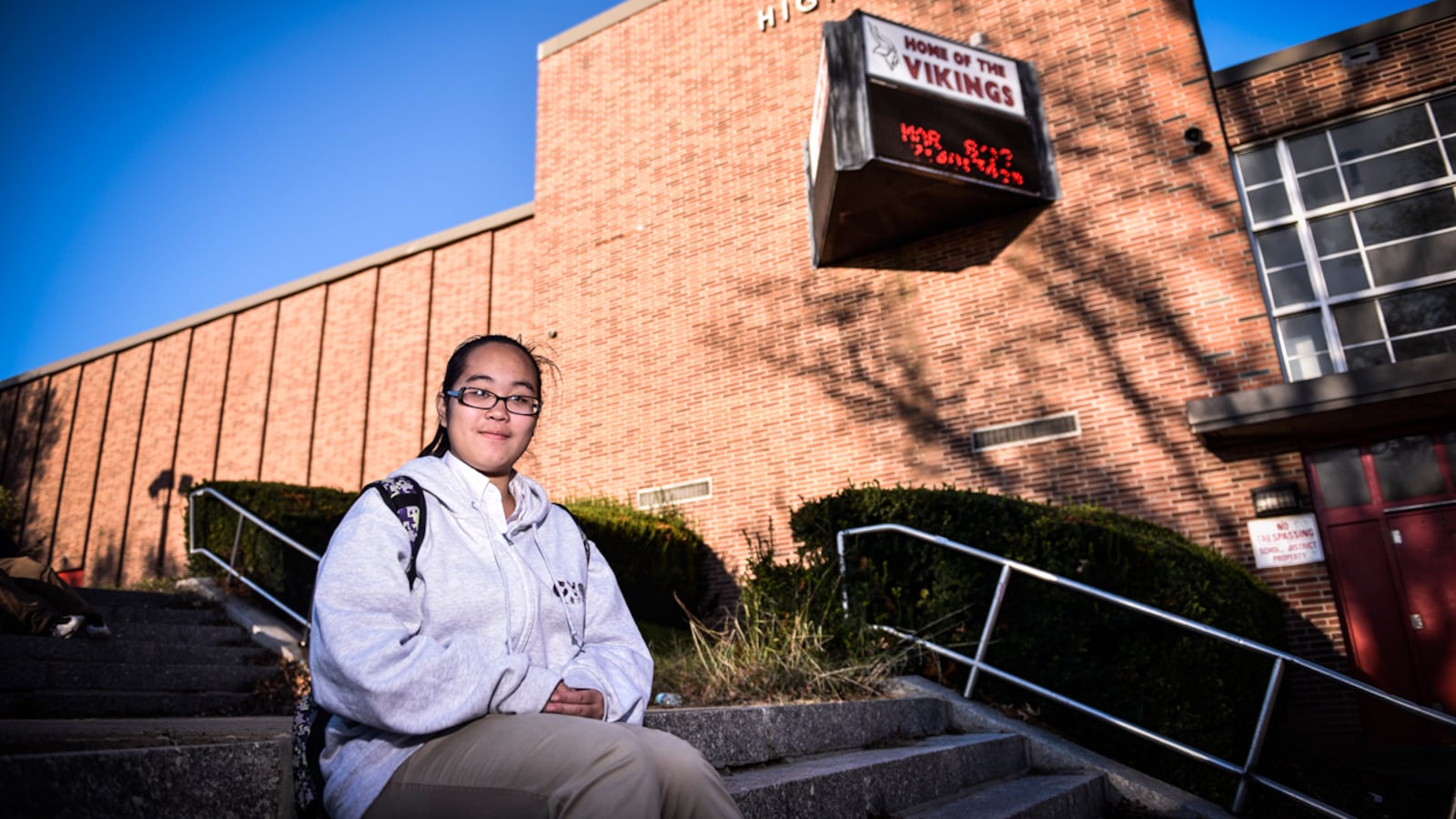

Growing up in China, Janet Zheng got used to taking tests. But she also got used to getting the preparation she needed from her classes, which is why the American system makes no sense to her.

“You take this much test,” she said, holding her hands apart, “with this little knowledge,” pulling them together.

Zheng is a junior at Northeast High School. She’s aced the Algebra I Keystone exam and takes AP calculus. But the two other Keystones have been a struggle, especially Biology. The test material doesn’t line up with what’s taught in class, she said. Teachers try to help, but support is hit or miss, especially for English language learners like her.

And part of the problem, she said, is that everybody has so many other tests to worry about.

“Northeast is a good school, but we just don’t have time,” she said. “We don’t have, like, one month just for Keystones. PSATs is crazy enough.”

Zheng doesn’t think it’s fair to judge her or other students based on how she does on Keystones or similar tests. The way she sees it, if she does well on her SATs, she’ll be on her way to the college of her choice, no matter what.

“You didn’t pass the Biology Keystone, now you can’t go to college?” she said, shaking her head with smile. “That’s crazy!”

It’s for students like Zheng that the region’s “opt-out” advocates hope to grow their slice of a small but growing movement.

The goal, they said, isn’t just to get students to skip exams. It’s to pressure state officials to relax the demanding testing regimen, reduce the stakes for schools and students, and return control of the classroom to teachers and principals.

“When we make [it] known that we aren’t taking the test, we change the way they teach all year long,” said Tomika Anglin, of Parents United for Public Education, while speaking at a recent forum at St. Joseph’s University.

Anglin was one of the first to embrace the movement locally, opting her daughter out of PSSA exams in 2013. Since then, buoyed by a surge of concern about testing, opt-out advocates have found support in Pennsylvania districts of all kinds, urban and suburban alike. Many of their complaints are being echoed by educators and officials around the nation.

And this fall, a sudden bipartisan surge has lawmakers reworking the landscape in favor of opting out. In Harrisburg, a proposal to delay the Keystone requirements is advancing fast.

In Washington, a call from President Obama and a deal in Congress have the nation on the brink of a major rewrite of the No Child Left Behind Act, the federal law that has driven so much testing.

That would be a rare and “significant” moment of unity in a deeply partisan age, said Ted Kirsch, head of the Pennsylvania Federation of Teachers. Kirsch predicts “a bipartisan bill that not only has the support of the House and the Senate, but also of the president.”

In Philadelphia, District officials are getting ready for the shift. A newly formed task force will soon revisit and reassess their full range of assessments.

But another trend remains in place.

Testing is deeply embedded in state laws nationwide. Support for “data-driven decision-making” remains strong among many lawmakers and advocates. Education reformers and civil rights groups alike back aspects of the practice.

And in Pennsylvania, by law and practice, test data still plays a major role in decisions of all kinds, including teacher evaluation, school transformation, placement in magnet schools, and more.

Opt-out supporters think those policies will backfire, leading to an interest in what many see as a form of social protest.

“New York is in the lead, and it really took on strong in New Jersey last year,” said Alison McDowell, a parent advocate and opt-out organizer with the Alliance for Philadelphia Public Schools. McDowell recently joined Zheng at an opt-out conference at Temple University.

“I think Pennsylvania’s year is coming up.”

Defining the movement

Shakeda Gaines, a volunteer at Thomas K. Finletter School, said she felt empowered when discovering the opt-out movement because her daughter gets so stressed out during testing time. (Photo: Harvey Finkle)

“Opting out” is shorthand for declining to take a standardized test. Pennsylvania students are legally entitled to do so, but until recently just a few hundred skipped exams each year.

Those numbers began to climb significantly around 2012, as opting out began to pick up steam in other states, and parents and organizers spread the word.

In 2015, Pennsylvania’s opt-outs tripled from the year before, with more than 4,000 students declining to take the PSSAs. Most opted out formally, using the state’s official (and somewhat cumbersome) “religious objection” opt-out process.

But others opted out informally, simply refusing to take the test on the day it was given.

For Philadelphia’s Shakeda Gaines, whose daughter gets good grades but feels badly stressed when tested, discovering opt-out was deeply empowering.

“I remembered that I was a parent, and these are my children,” she said. “If I say they don’t take the test, they don’t take the test.”

Variations on Gaines’ attitude can be found in Pennsylvania communities of all kinds – urban, suburban, and rural.

Agendas and interests differ somewhat among those constituencies. Suburban communities often see tests as unnecessary intrusions that dilute quality programs. Urban advocates often see them as unjust demands on underfunded schools, engineered to trigger closures or charter conversions.

But what unites all sides is the belief that over-testing is undermining learning. Parents in cities and suburbs alike cite the same factors: stressed-out students, overburdened teachers, ever-rising test-prep demands and a distinct lack of valuable information from the entire process.

“The biggest change is how we spend the school day. It’s all about more time for instruction,” said Marissa Golden, a Lower Merion school board member and professor of political science at Bryn Mawr College. “I worry that tests encroach on well-rounded people.”

Even in her prestigious and relatively prosperous district, she said, arts and electives are down, test prep and remediation are up, and the test results produce little useful feedback for schools.

“It’s hard to use them as an educational tool,” Golden said.

The result is growing frustration among parents and administrators and one of the state’s highest opt-out rates. Last year, almost 300 Lower Merion students opted out.

One such abstainer is Katy Morris, a Lower Merion 8th-grade teacher and mother of two. She not only opted out her own children, but also told parents that she wouldn’t be interrupting her regular classroom schedule for any special test prep.

“I wasn’t going to throw on the brakes,” she said.

Instead she offered students the option of afterschool help or take-home test preparation projects.

“Parents came and said, ‘Thank you,’” she recalled.

Widespread discontent

Such opt-outs, while growing, represent just a tiny fraction of Pennsylvania’s 800,000 test-eligible students – about one half of one percent of the total.

In Lancaster County, for example, opt-outs have doubled each year for three years, but still involve just a few hundred students. In Philadelphia, the number of PSSA opt-outs jumped by a factor of about 30 last year – from about 20 students to 595, in a district of about 130,000.

But even where actual opt-outs are low, school officials are registering many of the same complaints as opt-out promoters: that testing has become intrusive, expensive, and counter-productive.

School boards statewide – Pottsgrove, Upper and Lower Merion, West Chester, Spring-Ford and more – have passed resolutions calling on the state to relax and rethink its test regimen. The Pennsylvania School Boards Association has done the same.

And in Muhlenberg County, near Reading, one school board member who struggled to solve rigorous new 4th-grade math problems said, “At some point, I start to applaud the opt-out movement. All we’re doing is teaching the test and then stressing the heck out of the kids for two weeks while we give them this test.”

All this suggests that the opt-out movement is less radical fringe than leading edge.

“They’re driving an important conversation, staking a position about how harmful tests are when they’re misused,” said Susan Gobreski, executive director of Education Voters Pennsylvania.

“There’s a place for testing, but it should be limited. … [We shouldn’t] load everything and the kitchen sink into the results,” she said.

Experiences in other states show that the movement can gain significant traction when conditions are right. In New York, fueled by unhappiness with new Common Core standards, refusal rates have reached 20 percent. Controversy over New Jersey’s tests has driven opt-outs there as high as 15 percent – leading to a new state law prohibiting financial sanctions for districts with high refusal rates.

And this fall, the movement got a national boost when the Obama administration endorsed new research showing that the average U.S. student now takes about 112 mandated tests between kindergarten and graduation – a system the report labeled “illogical” and “incoherent.”

In the wake of that report, by the Council of the Great City Schools, Philadelphia School District’s new task force will reconsider all of its assessments, accepting recommendations to make them more effective and less intrusive.

Among those welcome to join are opt-out advocates. Chris Shaffer, the District’s head of curriculum and leader of the task force, said, “I want to get something that’s representative of everybody.”

The downside of opting out

If the tide of public opinion is turning somewhat in the test skeptics’ favor, another trend has been at work too: one that has embedded testing ever deeper at every level of state and district decision-making.

Much of that trend has been driven by federal law. That may soon change – a tentative deal in Congress could eliminate a wide range of No Child Left Behind mandates – but for now, test data is still used to drive charter school conversions, teacher evaluations, and closures.

In Pennsylvania, even as lawmakers consider relaxing Keystone mandates, they’re also considering new, data-driven laws around teacher layoffs (replacing seniority as a deciding factor with performance scores) and school transformations (requiring districts to turn low performers over to charters or private providers).

In Philadelphia, exams and assessments of all kinds are now being given virtually every day to one group of students or another. These include diagnostics, benchmark tests, mandated PSSAs and Keystones, PSATs, SATs, NAEPs, and more.

And although students may face no formal penalties for opting out of a given test, they can definitely lose opportunities. PSSAs are already a requirement for students seeking admission to Philadelphia’s magnet middle and high schools. And for now, Keystone exams remain a a 2017 graduation requirement.

“There’s a lot of parents in Philly who might be happy to opt out their kids, to their kids’ detriment,” Gobreski said. “When test scores are used to help evaluate kids for magnet schools or college, parents have to weigh the choices carefully.”

Opting out is a chance that not every family can afford to take, Gobreski said.

“Well-off parents are in a better position to take risks,” she said.

Nor is it a choice all parents have time to worry about. Tonya Bah, a mother of two opted-out teenagers from Philadelphia’s Olney area, said, “In my neighborhood, folks are worried about putting food on the table.”

And for many, the concept cuts deeply against the grain of family culture.

“For achievement-oriented parents who want to be the best, these tests are one more marker,” said Lower Merion’s Golden.

Some parents, like Gaines, aren’t worried about any of this. If her daughter skips the Keystones and needs to get a GED to get into college, she said that she’s fine with that.

“Temple takes kids without diplomas,” she said. “She’ll still have her credits.”

But testing still has strong support in many political and advocacy circles.

“The system needs a feedback loop,” said Donna Cooper, executive director of Public Citizens for Children & Youth, who helped develop the Keystones as a top aide to former Gov. Ed Rendell.

Qualitative assessments are “the only available, consistent, and objective source of data about disparities in educational outcomes,” wrote a coalition of civil rights groups, including the NAACP, in a recent statement.

This fall’s developments in both Harrisburg and Washington could eventually bring significant changes to Pennsylvania policy – changes that could make it easier for legislators and administrators to reshape all of the state’s data-driven decisions.

“It’ll be interesting to see how it works out – if there will be a need for opt-out,” said Kirsch.

But for now, Pennsylvania’s basic testing framework remains in place, and parents like Bah hope the state can make the best of it.

“Should there be testing? Absolutely. But there needs to be some kind of response to the answers,” she said.

“I would like to trust teachers again, empower teachers again. I want to go back to where I can get something wrong on a test, and then follow up so I can correct what’s wrong.”