This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Notebook has a two-year grant from the van Ameringen foundation of New York to cover behavioral health in schools.

Although most of our coverage will be in Philadelphia, we will occasionally highlight programs in other areas where the work might be of interest to our readership.

We continue with this series, taking a look at behavioral health services in some Baltimore City schools and the differences those services are making for students.

Ebony Elliott had a stark, unflinching description of her West Baltimore neighborhood:

“Where life doesn’t matter any more.”

There is violence, drugs and despair. “The children have nothing,” she said. “They don’t even have a playground.”

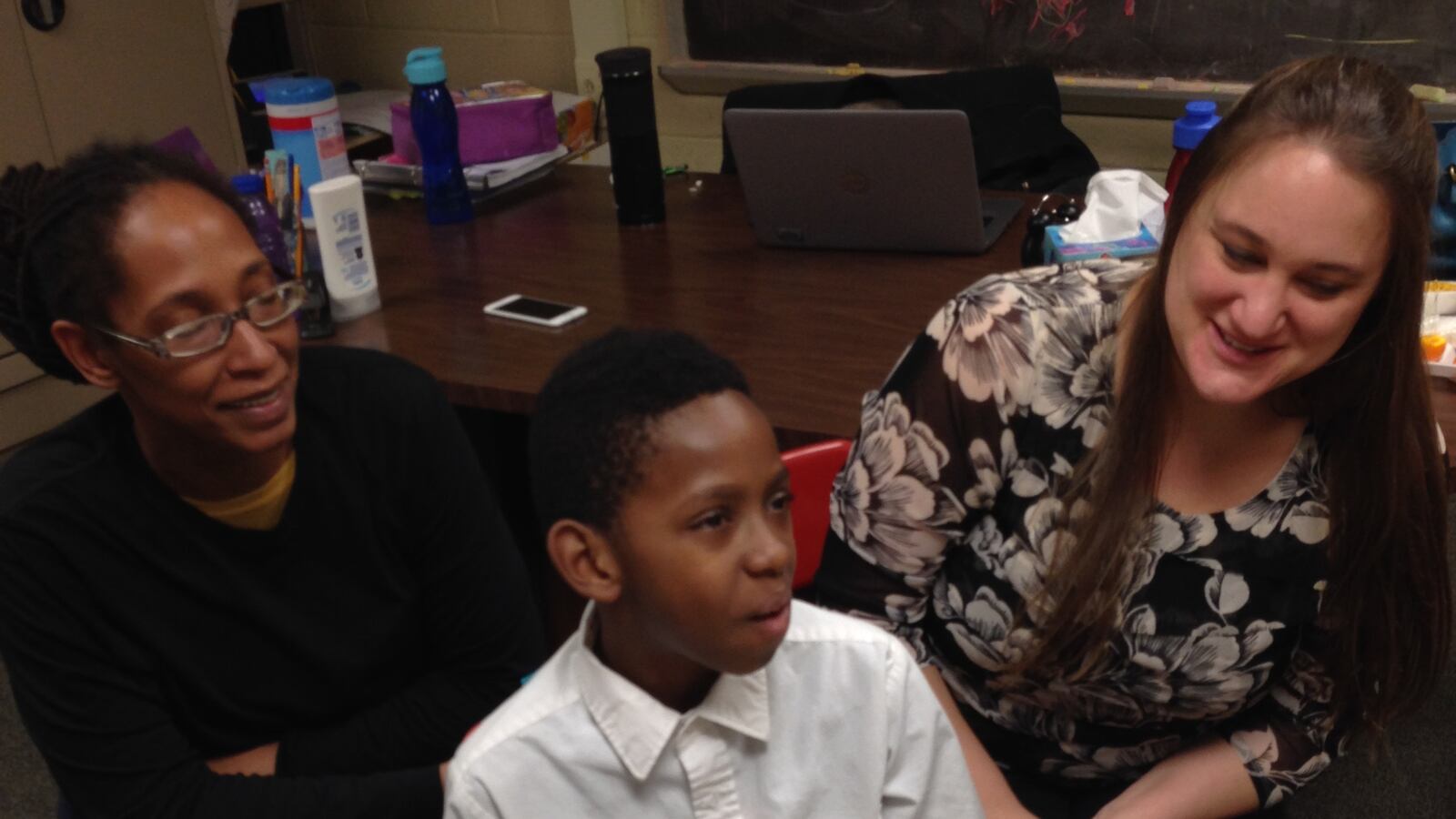

One of those children is her nine-year-old son, Ishmael Neuville, and as she sat in a classroom at the John Eager Howard Elementary School, she talked about her struggles with him and a ray of hope for both of them.

Ishmael, diagnosed with ADHD, was oppositional, resisting authority, having difficulty with self-control. “My child was crying out,” his mother said.

So Elliott, 40, reached out to school officials and soon Ishmael was seeing Aimee Hoffman, a school-based mental health clinician, on a regular basis.

Hoffman is with Catholic Charities, a provider working with the school system. She is stationed at Howard every day with the support of a federal grant to increase behavioral health services in 13 schools in areas affected by the rioting following the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody in March 2015.

Elliott says that Ishmael has improved dramatically as he works with Hoffman. "His attitude, the way he thinks things out. I’ve cried [over] him,” she said.

And Hoffman attributes her success partly to the fact that she is there every day, seeing Ishmael not just for the weekly sessions but also to ask in the hallway how he is doing, encourage him, give him a pat on the back.

“It’s knowing (the children) more in depth,” she said, seeing how they interact. Being there full time makes a huge difference.

“When you’re in a school part-time, you miss things and you’re not as visible to the teachers. When the teachers see you every day, you catch those extra opportunities to be supportive.”

Denise Wheatley-Rowe, of Behavioral Health System Baltimore, who heads the Expanded School Mental Health program, agrees.

“It’s being fully integrated in the school’s culture,” she said. ”If you’re not here as often, you don’t impact the climate the same way.”

Making a difference

David Guzman, principal of Matthew Henson Elementary School in West Baltimore, shook his head as he reached into his desk drawer and pulled out a box cutter taken from a fourth grade student.

“Some of these things are pretty staggering for an elementary school,” he said.

“This community is mired in so many challenges…violence, substance abuse, mental health issues. And even with no mental health issue, there’s a level of frustration.

“Every year we’ve had at least one parent be a victim of violence.”

Ten minutes later, though, his upbeat side showing, Guzman was addressing a Black History Month assembly, the audience dotted not just with students and teachers, but also with parents.

Guzman finds it a little easier to remain upbeat these days, partly due to the increased presence of behavioral health workers.

Five years ago – three years before he arrived – “We had a special ed teacher and that was about it.”

Now he has the equivalent of two full-time behavioral health workers, with a third on the way.

“It’s made a difference,” he said. There are things that used to fly under the radar.”

The additional help was sorely needed.

To take just one indicator, the zip code in which Henson is located -21217 – had the most incarcerated people of any zip code in Maryland, he said.

“You’ll sit in an IEP (Individualized Education Program) meeting with a second grader who’s already been in four or five different schools.”

The school’s alumni include Freddie Gray, and Guzman noted ironically that Gray had stopped by about two years ago, hoping to talk to one of his former teachers.

Three months later, Gray was dead.

“Working here every day takes a toll on [the teachers’] mental health,” he said. “I know it takes a toll on me.”

He had an elliptical, a treadmill. and a stationary bike installed at the school so teachers can relieve stress with exercise. He had wifi installed on the top floor so he can work there instead of being cooped up in his office all the time.

And if progress at Henson comes in small increments, he can deal with that.

“We’ve done a good job making this school a safe place,” he said.

Benchmarks of Success

The evaluation for the U.S. Department of Education’s Promoting Student Resilience grant will be done by the University of Maryland’s Center for School Mental Health.

It will based on six factors: discipline, academics, attendance, promotion, test scores, and school climate.

School climate will be a self-report from teachers, behavioral health workers, principals and others involved in the grant. The others can be objectively measured.

Nancy Lever, an associate professor of psychiatry at the center, said that the evaluation has benefited from the wealth of student data that the district provided and from the fact that her team was involved from the beginning.

“We weren’t coming in after the fact,” she said.

Brittany Parham-Patterson, an assistant professor in the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the Center for School Mental Health, is also developing an online trauma training module for the coming years.

“You can’t continuously get these (federal) funds,” she said.

James Padden, director of related services for the school district, said that while he hopes statistics on discipline, academics and graduation will improve, success will also have to be defined in terms of intangibles.

“We’re looking for an environmental change, a cultural change, where students feel safe, empowered and connected to adults,” he said.

“Trauma takes away choices. Empowerment gives them back choices.”

When that happens, he said. “You can feel the climate, the culture when you walk in the door.”

Paul Jablow is a freelance writer who contributes frequently to The Notebook and is anchoring our mental and behavioral health coverage.