This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Sixth-grader Samantha Sandhaus’ question was so innocent – simple and logical – that, for one brief moment, it silenced two seasoned, and loquacious, politicians.

Why, the 12-year-old wondered, if the city of Philadelphia can’t legally make laws to curb access to guns, then “why doesn’t the federal government do it?”

Aaah, why indeed? Where to even begin?

That was the look that crossed the faces of State Rep. Jordan Harris (D, Phila.) and Philadelphia City Councilman Kenyatta Johnson. The two had been tapped to deliver a primer on gun laws Tuesday at #PHLYouthTalks: Gun Violence from Parkland to Philly, a gathering at South Philadelphia High School.

The session, which was sponsored by the Philadelphia Youth Commission and the Mayor’s Millennial Advisory Committee and took place three days after the anti-gun violence march in Center City, drew about 80 people; about half of them were students. They listened to the politicians, including Mayor Kenney, before dividing into smaller sessions on trauma, creating safe spaces, and anti-violence programs — all in response to the Valentine’s Day shooting that killed 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Harris gamely took the first stab at answering Sandhaus’ question, talking about finding ways to shut off the access that people have to guns. Johnson chimed in, urging Sandhaus and others to mobilize against the National Rifle Association.

“No child should worry about being shot in school,” the mayor had said earlier, pointing out that “so many students grow up with violence and trauma that they don’t know any other way to deal with it but to get stuck in that cycle themselves.”

“Together,” he said, “we are stronger than the gun lobby,” particularly as young people assume leadership. “I’ll feel very confident that you folks are in charge,” he said, describing the generation of high school students as diverse, respectful, and willing to help each other.

Johnson and Harris outlined the city’s track record of gun violence – pointing out that Philadelphia ranks second among major cities in the nation in the percentage of homicides caused by guns. They urged audience members to get involved in government action and anti-violence groups. They advised students to learn about signs that classmates were struggling with mental issues and to take their concerns to adults.

And they said that although they respected the activism of the students in Parkland, Florida, they needed to see some of the same outraged response to the daily gun violence that claims the lives of black and brown people in Philadelphia. “People are dying on a daily basis from gun violence,” Johnson said.

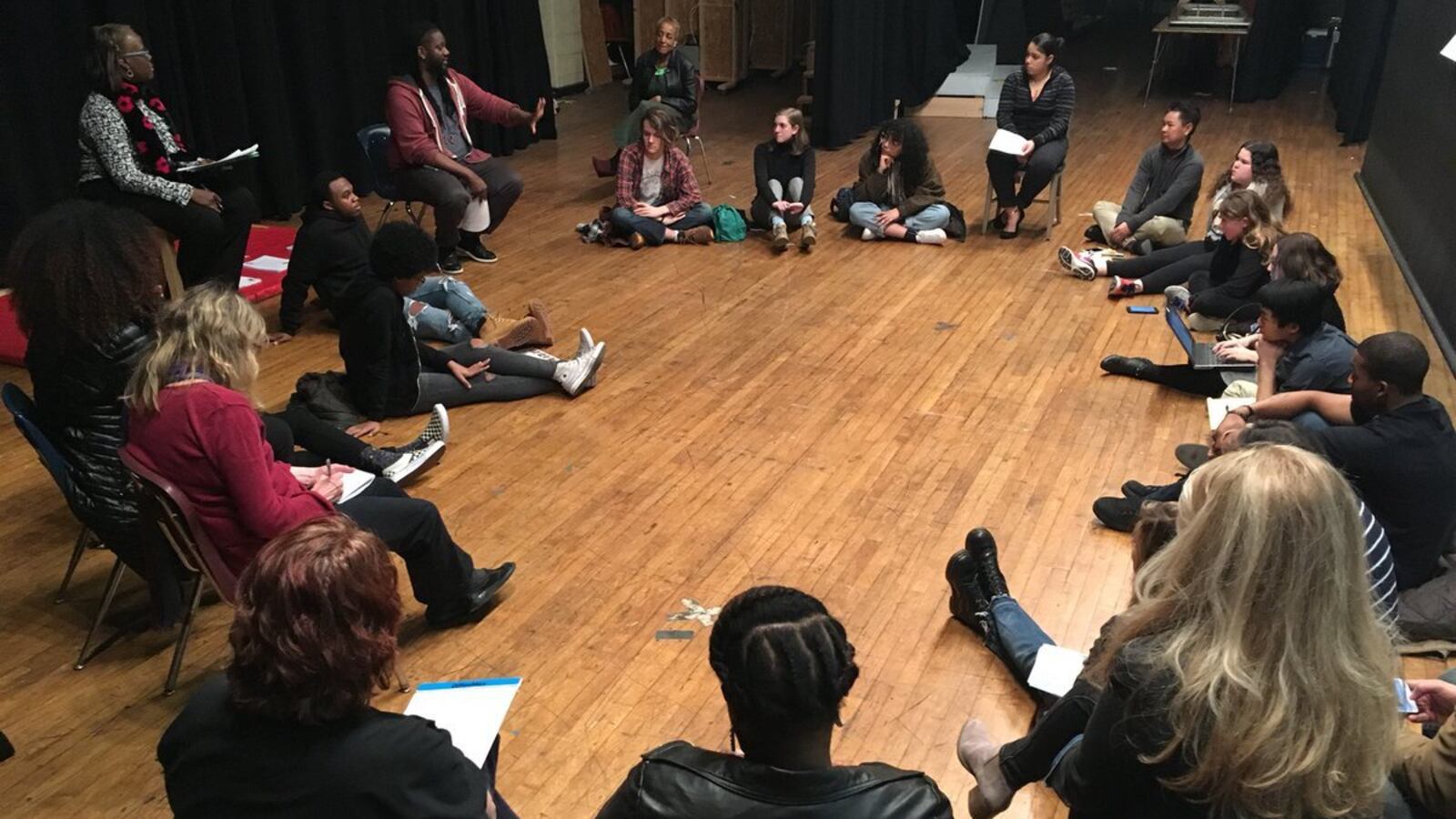

But nothing they said seemed to really address what was on Sandhaus’ mind. It came up as she almost curled in on herself, sitting on the floor with the others during the breakout session on trauma held on the high school’s stage behind a movie screen.

A student at New Foundations Charter School in Northeast Philadelphia, she said she’s scared, afraid to go to school. “You don’t want to go to school, [worrying that] this is our last day,” she said.

She defined trauma as “the fear in the back of your head. You can’t escape the fear and you feel like it might happen again.”

In the group of about two dozen, three-quarters of them raised their hands when asked whether they personally knew someone or had heard of someone who had been involved in gun violence.

They aren’t sure where to go to find help. Maybe they would turn to their counselors, one high school student said, if more of them were black like he is. But even then, he said, there’s a risk. By law, he said, they have to report abuse. So, if something’s going on at home, students may feel they can’t confide, he said, for fear the counselor will alert government officials who might break up their families.

It seems, one student said during the breakout session, that no one really cares about the steady devastation that gun violence causes each day in Philadelphia. The mass killings in a suburban Florida school got the headlines, deservedly, but when gun violence happens in Philadelphia, the broadcasters say, “A black teen in Philly dies, and now, here’s the weather,'” she said.

Youth Commission member and group moderator Tatiana Amaya, 17, a junior at Mastery Charter’s Shoemaker campus, had an uncle who was shot and killed last year. She said the experience made her even more determined to fight against gun violence because it gave her a deeper understanding of the impact on victims.

“Take what you learned here and apply it outside this group,” she urged at the end of the session. “Don’t let this conversation be the end of it. Expand it, grow it, learn about politics, learn about the political process and hold your elected officials accountable.”

The van Ameringen Foundation is supporting two years of Notebook reporting on trauma-informed education and behavioral health. This article is part of that reporting.