The spike in Philadelphia youth involved in gun violence has staff at the school district’s Juvenile Justice Services Center School calling for help.

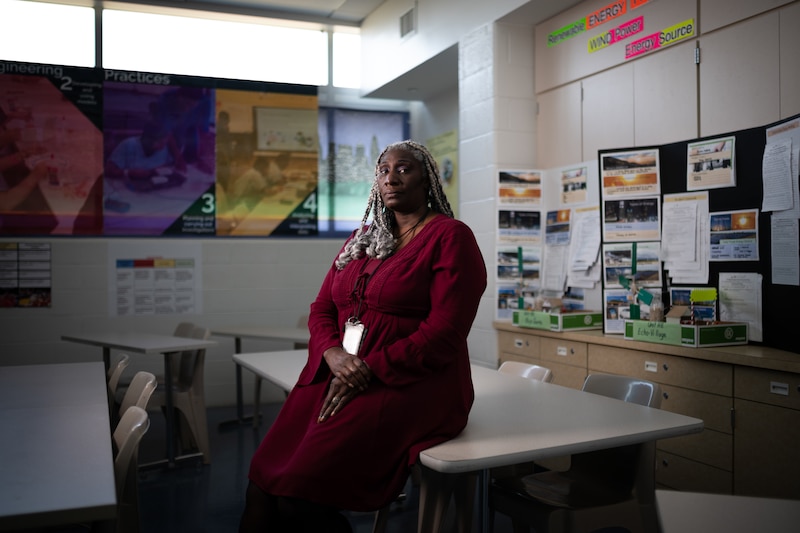

The goal of the center’s school is to keep students on track with their education and help them transition back to a traditional school after their arrest. But Principal Deana Ramsey said the rise in gun violence has not been met with an increase in staffing or mental health supports, leading her and others to worry the center isn’t fulfilling its mission to students.

The city’s gun violence crisis, coming amid the coronavirus pandemic, has put pressure on the West Philadelphia center, whose students accounted for 12.7% of all shooting victims enrolled in city schools through April of last school year, according to school district data.

There were 753 public school students shot last school year through April 2021. Students at the juvenile center accounted for 96 of those victims, the largest amount of any school. The second highest was 26 at Martin Luther King High School.

“I’m seeking professional assistance from every agency to help us out,” Ramsey said. “I think we do a great job when young people come to us, getting them to jump start again in a positive direction, and supporting them to go back into the community and not become involved in a negative situation, often ending up losing their life.”

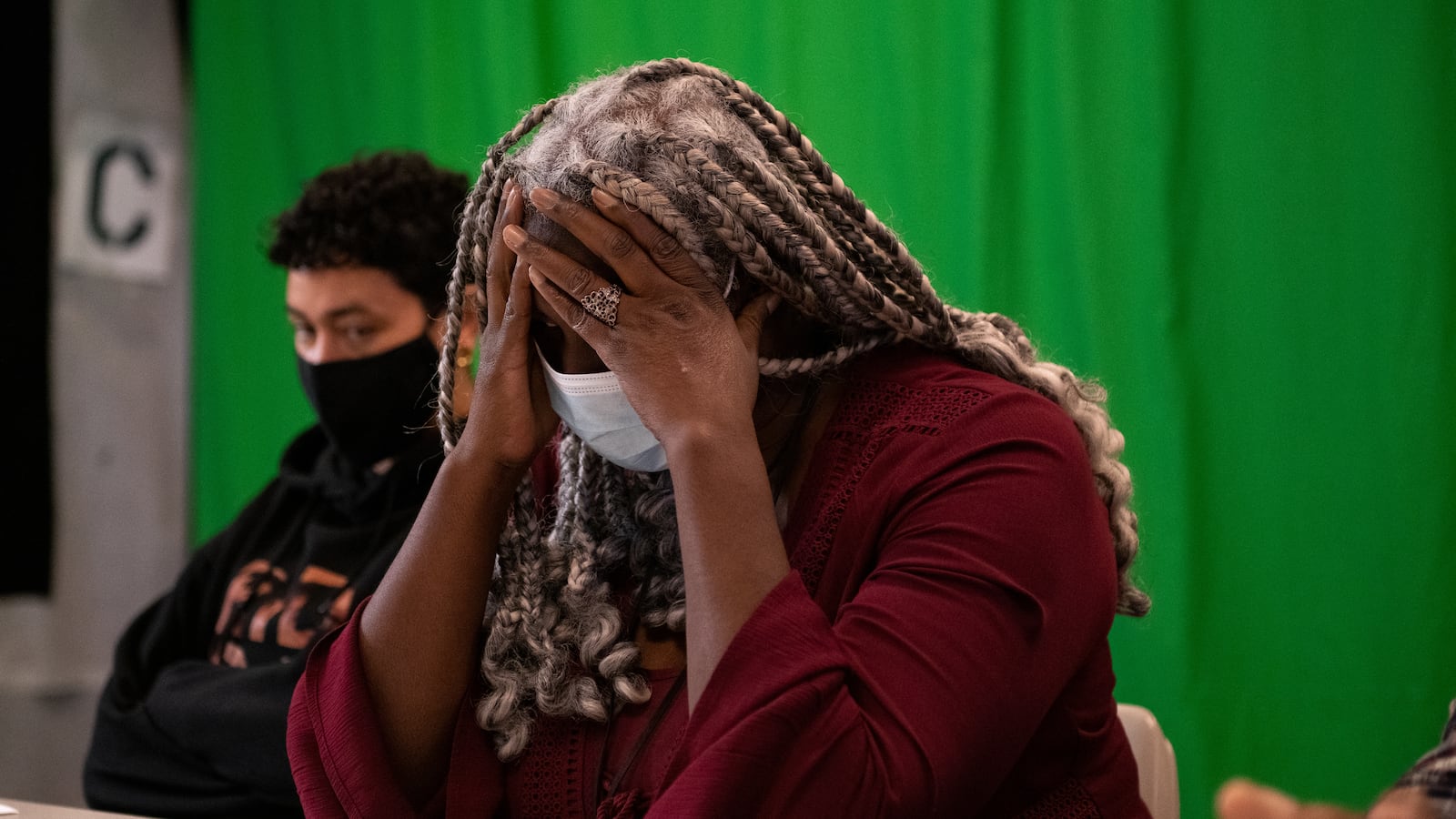

Echoing nationwide concerns about student mental health, Ramsey believes the school needs more group counseling sessions and support staff to assist students. “I also need more case managers to follow the young people whether they’re here for one day, or if they’re there for 365 days.”

Violence in Philadelphia has reached historic levels, with the city surpassing 500 homicides this year, the highest number since 1990. Teenagers and children have been swept up in this surge. Police statistics show that through mid-November, 31 fatal shooting victims were under the age of 18 — more than in all of 2020 and triple the number in 2015. And 30 people under the age of 18 have been arrested for gun homicides this year — six times more than 2019, according to police data.

Kevin Bethel, who serves as the chief of school safety for the district, thinks increased access to guns on the streets is trickling down to the youth.

“It just becomes a part of the natural process of the street, when you’re seeing a lot more violence, a lot more gang activity, a lot more of everything, and then you’re going to get young people say, ‘I’m going to get a gun too,’” Bethel said.

Student enrollment at the juvenile center is lower this year with 1,472 students compared to 1,866 in 2020. Though lower, 49% of the students are staying longer than 30 days at the center, which means they face more serious criminal charges. This percentage is the highest over the last four years.

Many of the students arrive at the center with learning disabilities and emotional issues compounded by the strain of facing criminal charges. Students have faced bullying, suffered from domestic violence, been shot, or shot others, Ramsey said.

Even before the rise in gun violence, Ramsey had arguably one of the toughest jobs in Philadelphia education. Still she has embraced the task of helping students facing criminal charges work toward graduation, earning accolades for her stewardship of the school, including the prestigious Lindback Award for Distinguished Principal Leadership in 2018.

Ramsey, a native of the Nicetown area of North Philadelphia and graduate of Roxborough High School, arrived at the center eight years ago, after stints at other district schools, including as assistant principal of Kensington Creative & Performing Arts High School. It was at the juvenile center where Ramsey finally felt she could make a difference in students.

“Business as usual from the past years is not working. Systems and communication are the two things our students need us to do better. We need to allow the students to have a voice.” Ramsey said.

While Ramsey’s concerns mirror those of educators nationwide who feel ill equipped to tackle mental health issues from the pandemic, those problems are intensified for her student body, which fluctuates daily but has hovered around 130 students in recent weeks.

“Right now, mental health is a big key piece to all of this,” she said. “If you’re in trauma and you have lost your best friend and no one is talking to you and giving you the skills to be able to cope with the death, you just become angrier.”

Inside the juvenile center’s school

The juvenile justice center, run by the city’s Department of Human Services, or DHS, is an expansive, modern building with steel beams, large windows, and manicured lawns. At the entrance, there’s a sign-in area, metal detector, and waiting space like a traditional prison. But through a pair of double doors sits the education area that resembles a typical school, with beige-walled classrooms trimmed with poems, classwork, and artwork by students.

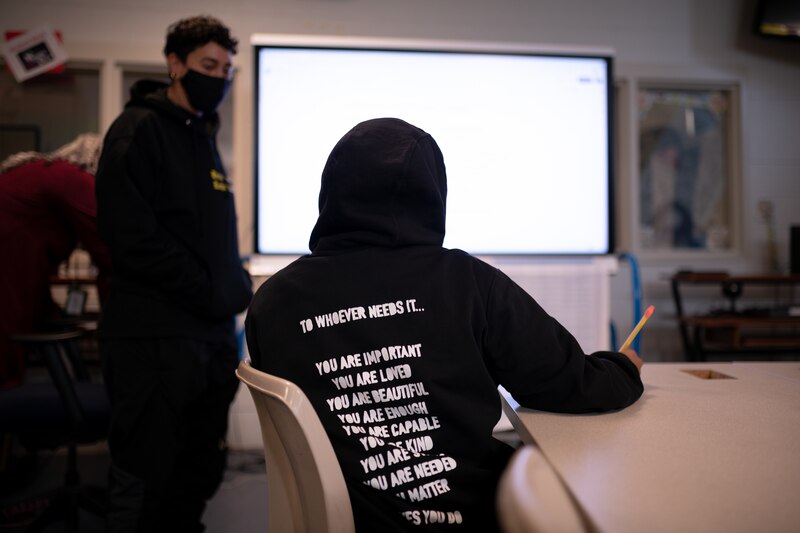

In some ways, the center is like other high schools. Algebra, biology, chemistry, physical science, art, and music are traditional courses that are taught by the center’s teachers, many of whom are dual certified to teach different courses. But the curriculum also focuses on accountability and understanding the trauma of the arrested students who arrive there.

Ramsey said the center’s school is essentially “where the rubber meets the road” in an attempt to help troubled students from becoming career criminals.

Within 24 hours of being taken into custody and arriving at the juvenile center, students are processed by admissions, allowed to call loved ones, and assigned a housing unit. They receive a medical assessment, meet with an attorney, and see a judge all within the first day.

Then they report to school.

Students receive a reading and math assessment, and staff determine where they last went to school and how many credits they have. From there the learning begins, with at least four classes a day. When Ramsey arrived at the center in 2013, she had nine teachers and five support staff. Today she has a total of 42 workers — 21 teachers, six special ed instructors, and the rest support staff.

Ramsey has been able to increase staff numbers over the years through an annual needs assessment, part of a school improvement plan where gaps are identified. She checks data, student enrollment and crime trends over time to determine what she needs to help the students earn the credits needed in order to graduate. But that assessment hasn’t taken into account the recent surge in gun violence.

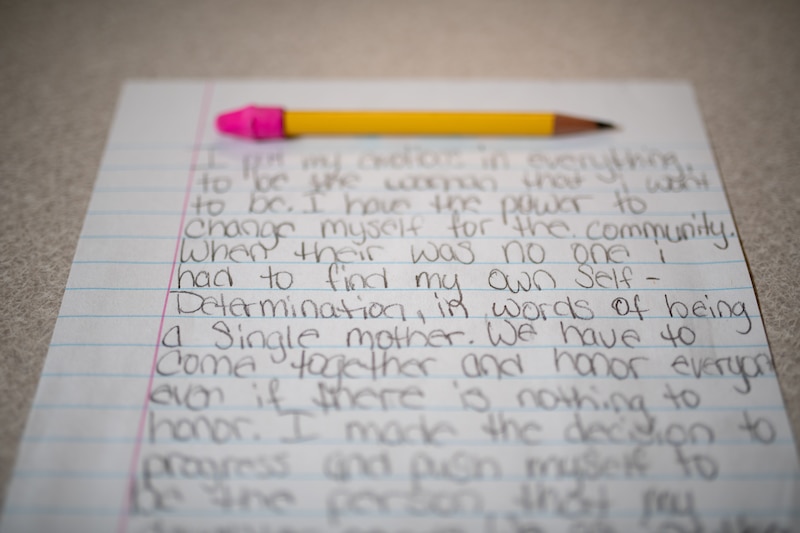

Teacher Selina Carrera, who won a Lindback Award last year, said what’s most important for the students is creating a social-emotional space for them to process their circumstances and also believe that they can be successful going back to school or have a career on the outside. Counseling theory is included in her class where she discusses life skills and allows students to express themselves creatively.

Some escape their pain by writing and recording rap songs. One student rapped about missing the birth of his child: Now I’m at the Youth and about to go to placement / My son about to be born and I’m mad that I can’t make it / Had to put the guns down and stay up off that gang isht.

Carrera said the goal is to “turn hurt into resiliency.”

Staff at the center aim to address needs beyond the students’ education. DHS said the office examines youth admitted to the juvenile center for behavioral health needs, too. “The team screens for challenges like depression, PTSD, suicide, and anxiety. And they provide evidence-based counseling and therapy based on the screening results,” the office told Chalkbeat.

There is one child psychiatrist and two clinical therapists on site, and DHS said it is collaborating with district teachers on mental health promotion groups. Its team is being trained in cognitive behavioral interventions for trauma in schools, with a new racial trauma component to be rolled out in the coming months. Therapeutic groups in general plan to resume after being suspended due to COVID-19 safety concerns.

Chalkbeat spoke to one student who has been in and out of the center over the past several years. The 18-year-old, who was involved in gun crimes and spoke on condition of anonymity, has been at the center since January.

He credits the center with helping him transition to adulthood, enabling him to earn his high school diploma at age 16. The student, a father of three, hopes when he leaves the center it will be for the last time. “My goal is to never come back to this center,” he said. “I want to be home with my kids and be a father to them. I’ve been here too long and it’s time for me to be home with them.”

His message to students involved with guns is to look at the bigger picture and consider the outcome. “Who is it done for or is it just for show? Is it so your friends can say ‘My homie got a gun,’” he said.

Now he sees clearly that the violence he has taken part in is “not worth it.” He thinks young people are missing parental involvement at home and not learning conflict resolution. Beefs can start on social media and spiral, with teens worrying too much about making a name, about their pride.

“I should have appreciated things more,” the student said. “Time is better than money.”

Getting students the help they need

Students can stay in the center anywhere from five days to 10 months, until there is a disposition in their criminal cases. For some, the next stop is a long-term correctional center. Others are set free, and a transition liaison from DHS is assigned to ensure the teen re-enrolls in school.

Those who have been there less than 30 days return to their previous school. Those who have stayed longer are assigned a new school placement.

A transition liaison from the center follows up with students and their families in regular intervals, checking to see if there are any barriers to them continuing their education. “It could be housing. It could be mental health. We are just trying to connect services with the young person so that they are successful and never return,” Ramsey adds.

The center is in the process of providing a digital version of its resource guide, with listings of agencies for parents and older students, said Thaddeus Desmond, STEP clinical coordinator at the center. “Being 18, 19 some may not want to go back to traditional school. So there are different programs for accelerated GED, credit recovery, ready-to-work programs, how to get insurance or different dental clinics. So anything that one may need this resource guide has,” he said.

DHS says that after students are discharged, they receive reintegration case management services for six months. Their family may enroll in community-based programs that offer support, and certain students who received psychiatric treatment at the center may qualify for a new, pilot in-home mental health service that provides therapy and medication management.

The department said its staff at the center is being trained in trauma intervention and plans to roll out trauma support groups for students in the coming months. Therapeutic groups that were suspended during COVID have restarted.

Still, Ramsey believes there is room for more to be done to assist students once they leave — and ensure they don’t return.

Ramsey admits feeling frustration that she can’t check on the students herself and questions whether more support during this period would cut down on recidivism. To date, 599 students have returned to the center this year, the highest in recent memory.

“Once they walk out that door from being discharged, that is it. That’s why you have all these repeaters. All the young people that keep coming back because nobody is really tapping in and making sure that they’re okay,” she said.

The staff at the juvenile center are also worried about a population increase caused by juvenile justice reforms, allowing youth once arrested for adult crimes and sent to Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility in the Northeast to now go to the juvenile center in West Philadelphia. DHS said it’s prepared for this transition.

“We are in the implementation stages of carving out space for the residents,” a DHS spokesperson said. “We are increasing staff hiring, working with district officials to ensure there is no lapse in education for the residents, and ensuring that programming is more appropriate for incoming residents.”

Ramsey remains worried.

“We are educators, we’re not law enforcement officers. We did not go to school to be social workers. We went to school to teach a child how to read and write. School administrators are really struggling and we don’t know what to do,” Ramsey said.

If you are having trouble viewing this survey, go here.