Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

When Danielle Edwards, 19, heard her alma mater, Paul Robeson High School, is on the list of schools the School District of Philadelphia wants to close, she messaged former classmates she’s still in touch with.

“That was my first school that I actually loved,” she said.

The district released plans last month to close 20 schools, including Robeson, as part of an effort to address problems with school facilities and declining enrollment. It wants to move students from Robeson into William L. Sayre High School as an honors program.

It’s a familiar and painful challenge for Robeson.

In 2013, a state-appointed board closed 24 schools in a contentious decision that drew months of protests. Robeson was initially on the list of schools to be closed, but it narrowly escaped that fate after intense pushback from the community.

Back in 2013, the fight to keep schools open was fierce. Teachers, students, advocates, and political leaders formed human chains, phone banked, shut down Broad Street, and swamped public meetings demanding their schools be left alone. Mayor Cherelle Parker, then a state representative, called on the City Council to keep one school in her district from closing.

For some schools, it worked. More than a dozen schools originally on the closure list ended up staying open and continued educating students for more than a decade.

But now, four schools or buildings that the district initially planned to close 13 years ago are back on the closure list: Robeson, Robert Morris School, Overbrook Elementary, and Lankenau High School. Mayor Parker has come out in support of the plan.

Without the same level of community pushback so far, advocates say they’re worried they may not be able to muster the support to save them again. And this time around, they have to convince members of a school board who have different aims and political influences from the several state-appointed board members of 2013.

District officials say they’ve learned key lessons from the 2013 closures when it comes to tradeoffs and consequences, and that the plan will ultimately benefit students when it comes to learning and early learning.

The district plans to present its plan to the board, which will determine which schools to close, on Feb. 26. A vote will come sometime afterwards.

Longtime Robeson teacher Andrew Saltz, who protested the last round of school closures, said he plans to try to save Robeson once again.

A lot in his life has changed since the last protests. He’s older, and has children. Still, he said, he’s finding the energy to fight the closure plan again; he’s said he’s heard from freshmen who are scared about where they’ll go to school if Robeson closes.

“This is the right thing to do,” said Saltz. “So, OK, let’s get it going.”

School leaders say different forces are driving school closures

Just like for Saltz, a lot has changed for the city and its schools since 2013.

The mayor and city council now determine who sits on the school board, rather than some members being appointed by the state. Superintendent Tony Watlington, who joined the district in 2022, has stressed that the perspectives of teachers, families, and community members will help shape a new facilities plan.

Still, there’s an expensive and persistent challenge: repairing old school buildings and operating schools with fewer students. District enrollment has declined, leaving some schools — including two of the four on the closure list for the second time — more than half empty. Old buildings have further deteriorated. During this winter’s cold snap, the heat in several classrooms did not work properly.

In 2013, the School Reform Commission that controlled the city’s schools cared largely about saving money. The district was cash-strapped and laid off nearly 4,000 employees before the first day of school.

District enrollment was also rapidly declining at the time — though for different reasons than it is today. In the years before the closures, the School Reform Commission had ceded district schools to charter organizers and approved other charter schools to open in the city.

But since control of Philly schools returned to the city at the end of 2017, district enrollment has declined largely because of falling birth rates. More Philadelphia students also now attend cyber charters.

Researchers found that some students’ academic performance took a hit after the 2013 closures, and absences increased for students who were displaced. Several school buildings were also left empty and deteriorating. And communities’ trust with school leaders was fractured for years.

“It was not worth the cost,” Deputy Superintendent Oz Hill told families in late 2024.

School leaders say the new proposal to close 20 schools and co-locate and relocate others is meant to provide more opportunities for students and families, like increased access to pre-kindergarten and AP classes. It also would result in students no longer attending school in buildings the district deems unsatisfactory.

But many say they’re worried the same harms stemming from the 2013 closures could happen again. The plan would move hundreds of students to lower-performing schools and disproportionately affect Black students.

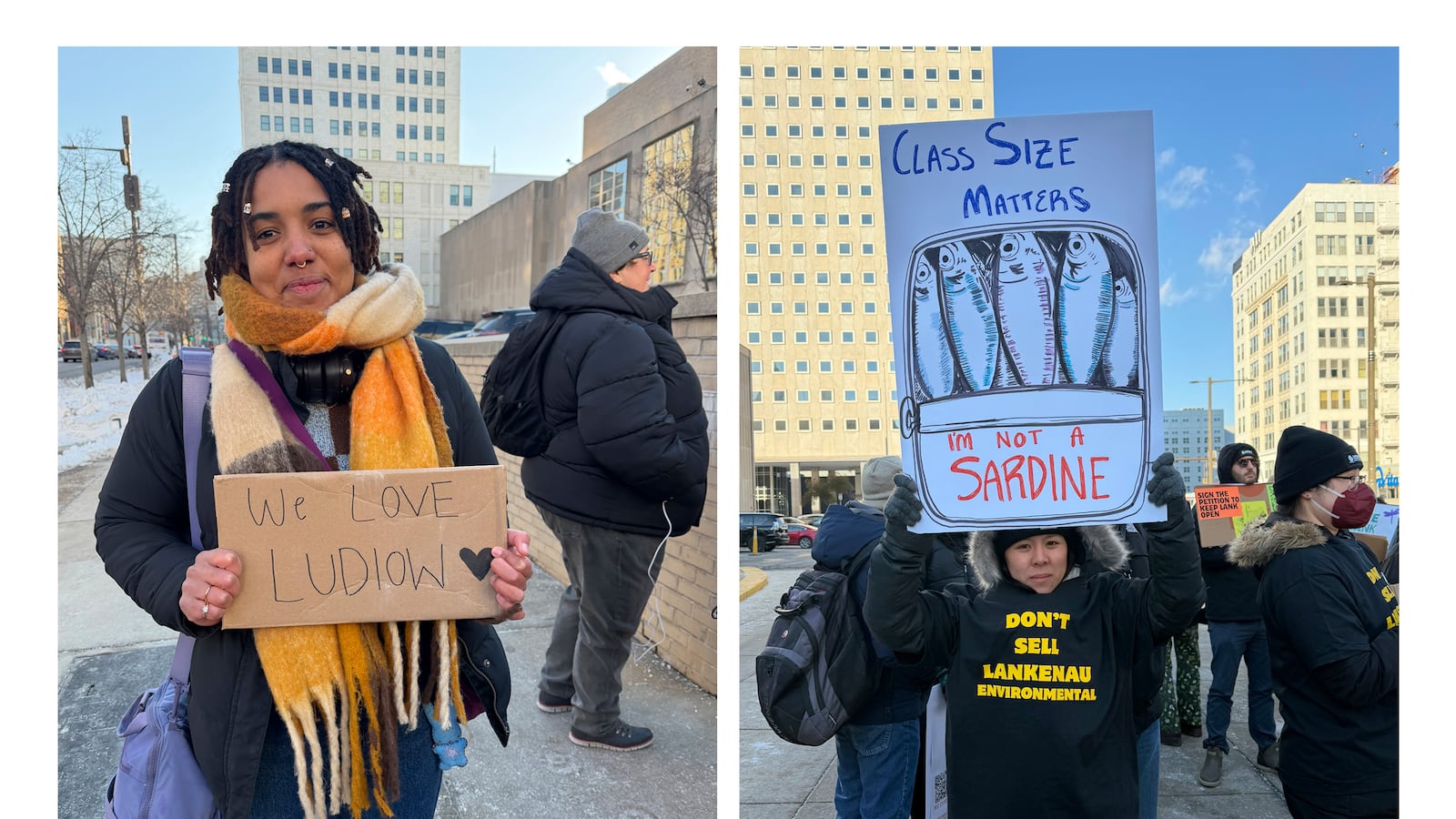

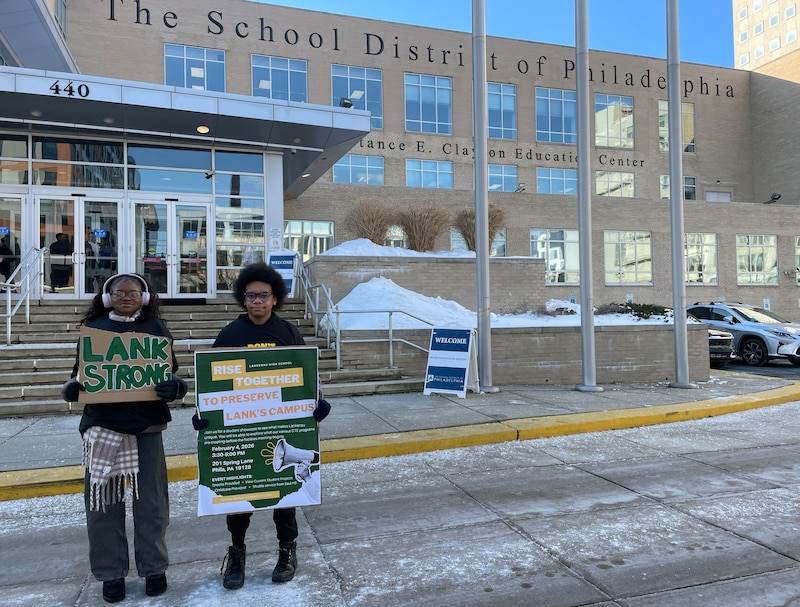

Protests against some of the proposals have already begun. Some members of the City Council have spoken out against the plan, calling on the district to change which schools it plans to close.

Viery Ricketts-Thomas, a block captain in Overbrook, said she feels shocked the neighborhood’s elementary school could be closed.

Since 2013, the school has gotten a new principal, Kenneth Glover, who has launched initiatives to partner with community groups to build a new schoolyard and attract more Black teachers who reflect the student body.

Though Overbook’s building is rated as poor, the school is enrolled at nearly 80% capacity, according to district data. Its students’ math and reading scores on state tests have also improved over the past three years.

“Right now the school is thriving,” said Ricketts-Thomas. “These are kids you’re displacing.”

Why fighting school closures might be harder now

Philadelphia teacher Jon Hoffmeier has fond memories of his two years teaching at University City High School. It was his first full teaching job in the city, and he loved how students had space for soccer practice and football practice.

The school closed in 2013. When Hoffmeier drives by the school’s old address, he now sees a parking garage. “It’s an absolute shame,” he said.

Hoffmeier was one of hundreds of teachers who had to move schools after the last round of closure. Now at Lankenau High School, he and other teachers are already fighting to keep the school open. They’ve launched a petition, made posters, and organized a rally at their school.

But not all schools are mounting the same response. Julia McWilliams, co-director of the urban studies program at the University of Pennsylvania, said the energy ahead of the 2013 closures felt different.

Advocates had been rallying for years against the School Reform Commission, and some were already organized across neighborhoods, she said. Schools bussed dozens of students to commission meetings and some groups threatened lawsuits.

Civil action intensified. Students at the now-closed Carroll High School in Port Richmond formed a “human chain” around their school in protest. The night the School Reform Commission read the final list of closing schools, a group of protestors blocked the entrance to the meeting and 19 were arrested.

Today, McWilliams said she worries there are fewer groups ready to call for changes, and many people may not have time or energy to put toward the cause. Some are busy with other issues, like organizing for immigrants’ rights. And many people may feel less passionate about protecting public education.

“What I’m seeing is just people don’t have a lot of confidence in public schools, because of what algorithms are telling them, because of what happened during COVID, because of the ways the teachers unions didn’t want to go back in-person,” said McWilliams. “People pulled their kids out and just never sent them back.”

Still, for some who plan to fight the closures, the new environment could fuel their motivation. With the city in control of its own schools, they say it’s vital for school leaders to keep many of the schools proposed for closure open to avoid repeating the mistakes of 2013.

Saltz, the Robeson teacher, remembers that ahead of the 2013 closures, it felt like “everyone already hated” the state-controlled School Reform Commission that oversaw city schools.

This time, he said it feels like the city is turning on its own schools.

“I think that made it more depressing,” said Saltz of the current closure plan. “Because you thought this school board would be different.”

Rebecca Redelmeier is a reporter at Chalkbeat Philadelphia. She writes about public schools, early childhood education, and issues that affect students, families, and educators across Philadelphia. Contact Rebecca at rredelmeier@chalkbeat.org.

Sammy Caiola covers solutions to gun violence in and around Philadelphia schools. Have ideas for her? Get in touch at scaiola@chalkbeat.org.