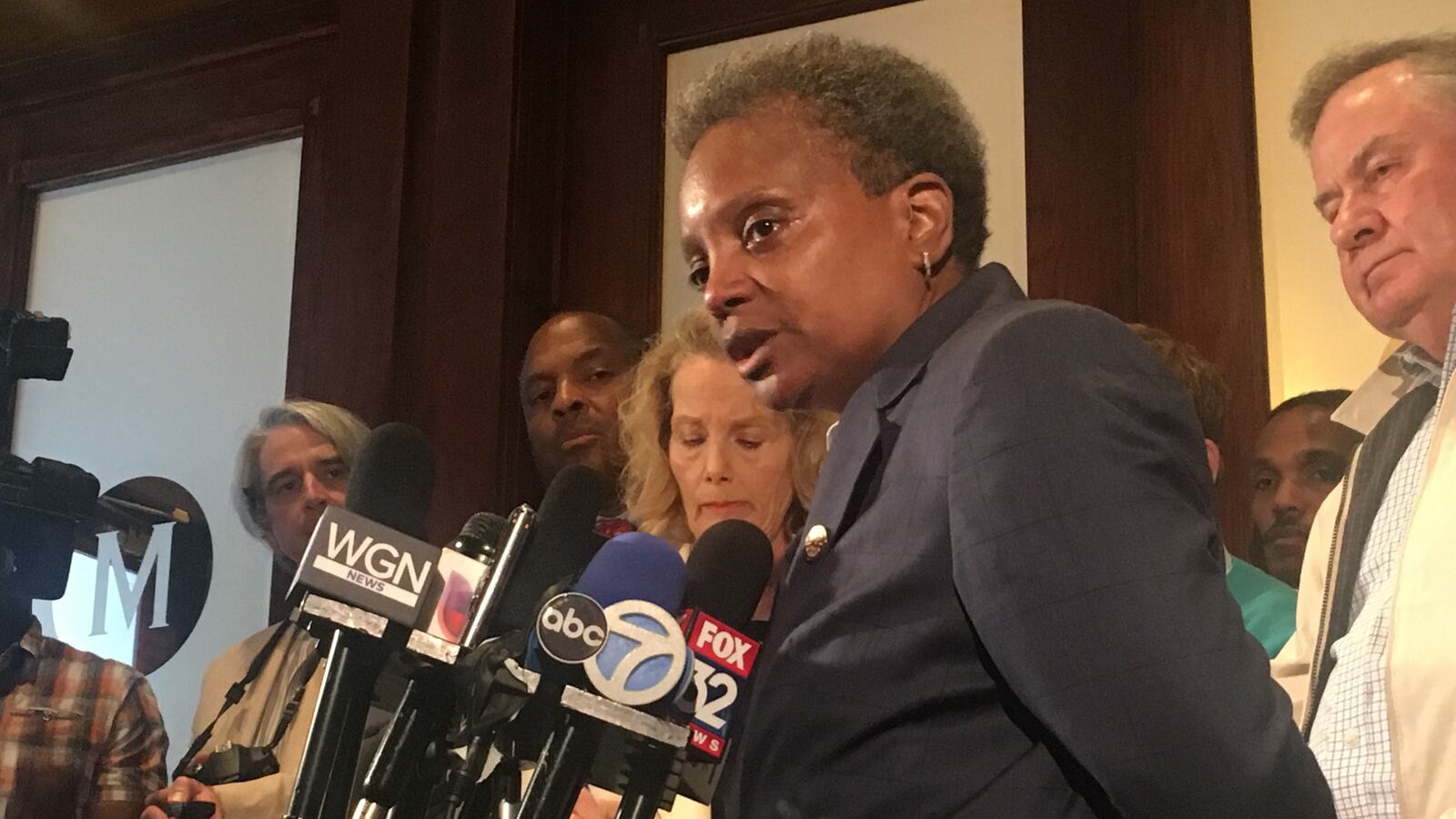

One of the many open questions facing Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s administration is whether to rethink the way Chicago funds its schools.

An unlikely group of allies, from a rebranded school choice group instrumental in charter school expansion to the Chicago Teachers Union, is ramping up lobbying efforts around the issue. Many of the groups submitted memos to Lightfoot’s education transition committee calling for a more equitable funding approach based on student needs.

Lightfoot’s team told Chalkbeat in a statement this week that the mayor is “firmly committed” to equitable funding and to ensuring that “schools and educators have the resources needed to support and address the needs of schools and families.”

Related: Good news for some schools in $32 million push, but questions surface about whether process is fair

Lightfoot has spent the last few weeks meeting with teachers, principals, parents and community members about education issues, “including school funding,” her spokeswoman said. But it was not clear whether Lightfoot will ask the district to revise the formula or whether she’s still in the exploratory phase.

“I think what we would like to see is a bit more of a sense of urgency around it,” said Gerald Liu, the policy director for one of the groups lobbying district leaders, Kids First Chicago, and who worked 11 years as a program manager and analyst at the district’s budget office. “You can’t talk about equity without talking about resource equity.”

Related: Here’s a closer look at Kids First Chicago, the group behind a report sparking debate

Chicago is one of at least 30 large school districts using weighted student funding, which tries to allocate funding based on individual student needs. The district allocates funds to schools based on the number of students, with high schools getting the most per-pupil, followed by grades K-3 and grades 4-8.

The district then provides some supplemental aid for students with disabilities, for those living in low-income households, and for schools with the highest concentrations of English language learners. The district also subsidizes schools with low or declining enrollment.

Related: Chicago is throwing its smallest high schools a lifeline. But is it enough?

But some of the groups lobbying the mayor contend that the district doesn’t allot enough money to certain populations that need more support, such as homeless students, refugees and students with other life circumstances that might affect their learning.

Other urban districts, such as Boston and Houston, take that approach, said Marguerite Roza, an education finance researcher studying whether such weighted student funding models close gaps in student achievement.

Lightfoot and other leaders stress the need for more state money to adequately support schools and pay for equity. But Roza said the district has discretion to more equitably distribute the money it does have.

“Districts are adding more student types,” she said. “Do you need an extra social worker if you have a lot of kids involved in the criminal justice system, or if you’re in a community with a lot of crime or trauma?”

Related: Trauma can make it hard for kids to learn. Here’s how teachers learn to deal with that.

Kids First is pushing for the district’s budget office to adopt its “equity index” budgeting tool, which considers factors like the incidence of trauma and violence in a neighborhood, or the concentration of single-parent households in a community. The organization detailed its proposal in a memo to Lightfoot.

Kids First Chicago has partnered with the district to help shape school choice in Chicago since the early 2000s — from funding charter school expansion, when the group was known as the Renaissance Fund and New Schools Chicago. More recently, the group has focused its efforts on parent advocacy, and helped compile a schools inventory report known as the Annual Regional Analysis. The district uses the report to help allocate resources and equip communities with the information to lobby for investments.

Constance Jones, CEO of the Noble Network of Charter Schools, suggested in a memo to Lightfoot that “schools with higher levels of poverty, English language learners, special education students, or nearby violence or crime should receive more resources to best meet the needs of their students.”

Katya Nuques, executive director of Enlace, called in her memo for the “creation of an education equity fund to close the achievement gap created by race, poverty, and overall lack of opportunity,” funded by fees levied on real estate development in the Loop.

Related: Are there alternatives to closing schools? Chicago parents consider options.

Parent advocacy group Raise Your Hand’s memo called for Chicago’s district to “allocate operating funds via a need- and evidence-based formula” that considers the specific needs of students there.

And as it negotiates for a new contract, the Chicago Teachers Union has repeatedly called for the district to adopt a more nuanced funding formula that accounts for students needs by school and community.

Even before the contract fight ramped up, the union was one of the most consistent voices railing against the district’s current student-based funding model, which they say makes it hard for schools with low enrollment to hire experienced teachers, especially black veteran educators whose salaries are more expensive. Union leaders say it contradicts the spirit of a 2017 Illinois law that updated the state’s funding formula and directed more money to districts most in need.

Related: Two-thirds of Chicago schools will get a budget boost next school year. Is yours on the list?

“This is a huge deal for us,” union spokeswoman Christine Geovanis said. “We want CPS to deploy resources on a school by school and neighborhood by neighborhood basis.”

In its five-year vision plan, Chicago Public Schools committed to reviewing funding models and exploring ways to support equity by investing more resources in underserved populations.

Since the plan was released in May, the district hasn’t provided any updates. But it appears Chicago’s school funding plan may shift, even if it falls short of the union’s demands.

Most Chicago schools will get a budget boost this fall as the city adds new programs and props up spending at schools with low enrollment. The district also spread $6 million among 100 or so schools with the highest concentrations of English language learners.

Related: In a shift, Chicago to prop up budgets at schools struggling to attract students

Overall, Chicago Public Schools will send schools $60 million more next school year than it did last year, according to the district. That growth reflects nearly $90 million in new programs and a $30 million decrease because of declining enrollment.

Two-thirds of city schools will see their budgets go up, according to numbers provided in the spring. A third of city-run schools will see their budgets decline.