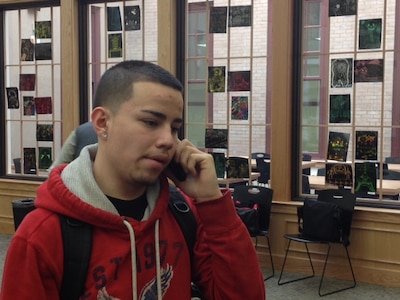

Brandon Garcia found himself getting in trouble a lot as a freshman at Denver’s North High School. He could easily be persuaded to ditch school or get into fights.

It wasn’t a surprise when he found himself in the principal’s office five years ago facing a lengthy suspension and possible criminal charge. He pondered never returning to school.

“I felt like I wasn’t supposed to be at school – that they didn’t want me there,” he said.

But his basketball coach intervened, asking if there was another way to handle Garcia’s lapses in judgment. There was, and it was called restorative justice. His suspension was shortened, and he did community service projects around the school and even came face to face with the guy he fought to get to the root of the disagreement.

Today, Garcia sees this as a pivotal moment. He graduated from high school, he works as a sales rep for Cricket and he’s scheduled to start classes at the Community College of Denver this summer. He wants to go into real estate or finance.

It’s stories like this that Denver Public Schools and the Denver Police Department are hoping to replicate through a revised intergovernmental agreement signed Tuesday at North High School that clearly articulates the role of school resource officers, often referred to as “SROs.”

The document, touted by its backers as the nation’s most comprehensive policy governing school safety and discipline, replaces one crafted and signed in 2004. While many SROs in Denver are already doing what the agreement calls for, backers say it formalizes the relationship between police and schools for years to come regardless of changes in leadership and represents a significant shift away from the zero tolerance discipline policies of a decade ago.

The revised agreement “simply now holds everyone accountable to the future,” said Steven Teske, a juvenile court judge from Georgia and expert on school discipline policies. “The superintendent and police chief are not going to be here forever.”

Key changes to intergovernmental agreement

The revised document calls for school resource officers to:

- Differentiate between disciplinary and criminal issues and respond appropriately;

- De-escalate school-based incidents whenever possible;

- Understand that DPS has adopted a discipline policy that emphasizes the use of restorative justice approaches to address behaviors and is designed to minimize the use of law enforcement interventions.

The document also has new protections for parents and students. They include:

- Notification of parents as soon as possible when students are ticketed or arrested;

- Notification of principals within a reasonable time when a student is ticketed or arrested;

- Questioning of students in a manner that has the least impact on a student’s education;

- Notification of SROs when students have disabilities or individualized education plans so that accommodations can be made if necessary.

The document also requires police stationed at Denver schools to meet with community members at least once a semester and to participate in meetings with school administrators when requested.

Finally, the new agreement requires training of SROs and school administrators on how best to deal with youth discipline problems – strategies that are also outlined in Senate Bill 12-046, the Smart School Discipline bill. Those training issues include child and adolescent development and psychology, age-appropriate responses, cultural competence, restorative justice techniques, special accommodations for disabled students and the creation of safe environments for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students.

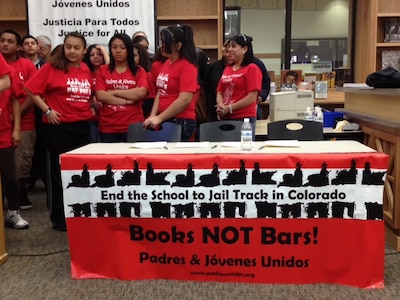

The tweaks to the agreement, the $1.5 million annual cost of which is shared by the city and school district, came after many years of discussions between district leaders and youth affiliated with Padres & Jovenes Unidos, a community organization that works for educational excellence, racial justice for youth, immigrant rights and quality healthcare. One of the organization’s key goals is to end the school-to-jail track.

Padres student leader Tori Ortiz said she watched friends’ lives unravel when they were ticketed by police for incidents that could have been handled differently.

“Day after day students were criminalized and targeted as suspects … for a minor offense that should have been handled by counselors and principals,” Ortiz said.

Ortiz said she watched as her peers were pushed out of school and “robbed of their potential in a split second.”

“Ticketing students is the wrong approach to solve an issue,” Ortiz said, adding that a suspension simply amounted to a week of video games, cartoons, sleeping in or taking a “stroll in the streets” for students.

National expert lauds Denver’s approach

Teske, the juvenile court judge who was invited to attend Tuesday’s signing, said Denver stands out from other cities because district and police leaders are willing to work with students.

“What happened here – grassroots efforts led by students and parents – combined with the mindful leadership of the school superintendent and chief of police, that is unique,” Teske said.

Teske said when he took the bench in 1999 his court was inundated with 1,400 mostly misdemeanor cases stemming from fights or disorderly conduct from the public school system. After the community tackled the issue and embraced restorative justice, the number of referrals plummeted to 49.

“Something drastic needed to be done,” Teske said. “We decided to no longer arrest kids on minor offenses. As of today, referrals have plummeted by 83 percent and graduation rates have increased 24 percent.”

“Kids are neurologically wired to do stupid things,” Teske said. “When young people are under neurological construction, it is important we place them in safe and positive places and not push them out of the safe and positive places.”

Teske said under the new system, school resource officers become role models for kids, building positive relationships that may also help them solve more serious crimes on the street.

DPS Superintendent Tom Boasberg said expulsions have dipped since the district started changing its discipline policies.

“The goals of (the agreement) are very simple and at the same time very profound,” Boasberg said. “We want to make sure our schools continue to be safe places to learn, safe places for our community to grow. We want to make sure we keep our kids in school.”

District officials said expulsions in the district last year dropped 60 percent from the past two years. However, students who face harsh penalties for breaking school rules are disproportionately African-American students, according to a report presented to the Denver school board in September.

There were 185 expulsions in 2009-2010 compared to 63 last year. The number of out-of-school suspensions has declined from 9,558 to 7,525 in 2009-2010 to last year.

“We are on pace this year to have our suspensions be one half of what they were three years ago,” said Boasberg, adding that dropout rates in the district have dropped 50 percent over the past six years as well.

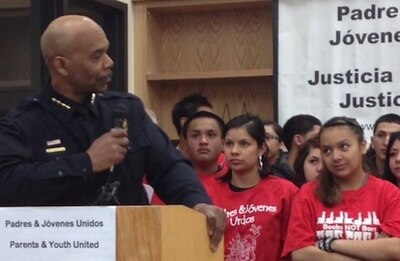

Denver police Chief Robert White encouraged the youth affiliated with Padres to continue working with all students so they understood the district’s goals and approaches toward restorative justice.

“(The agreement) makes the lines very clear,” White said. “We have no desire to be disciplinarians. That is a parent’s job and a school’s job. Our job is deal with serious violations of the law.”

White added, “We should do everything we can to keep young people from getting a criminal record.”

“This is going to help us.”

Location of Denver’s 17 school resource officers

- Abraham Lincoln High School

- Bruce Randolph 6-12 School

- CEC Middle College

- Contemporary Learning Academy

- East High School

- George Washington High School

- John F Kennedy High School

- Kepner Middle School

- Lake International School

- Manual High School

- Martin Luther King, Jr., Early College

- Montbello High School Campus

- North High School

- Skinner Middle School

- South High School

- Thomas Jefferson High School

- West High School Campus